A Profound Comedy:

Beethoven's Symphony No. 4 in D Major (1806)

Beethoven’s Fourth Symphony seems an anomaly compared to the heroic Third and the fateful Fifth. Many have commented upon its difference: the famous musical encyclopedist George Grove described the symphony as “a complete contrast to both its predecessor and successor…as gay and spontaneous as they are serious and lofty,” whereas composer Robert Schumann delighted in describing the work as “a slender Greek maiden between two Norse giants.”1 While such descriptions seem to argue against considering the symphony as metaphorically promethean, remember that storm and strife are but one aspect of being promethean. Listen below to Franz Welser-Möst’s take on this quandary:

Jean Paul and the 'inverted sublime"

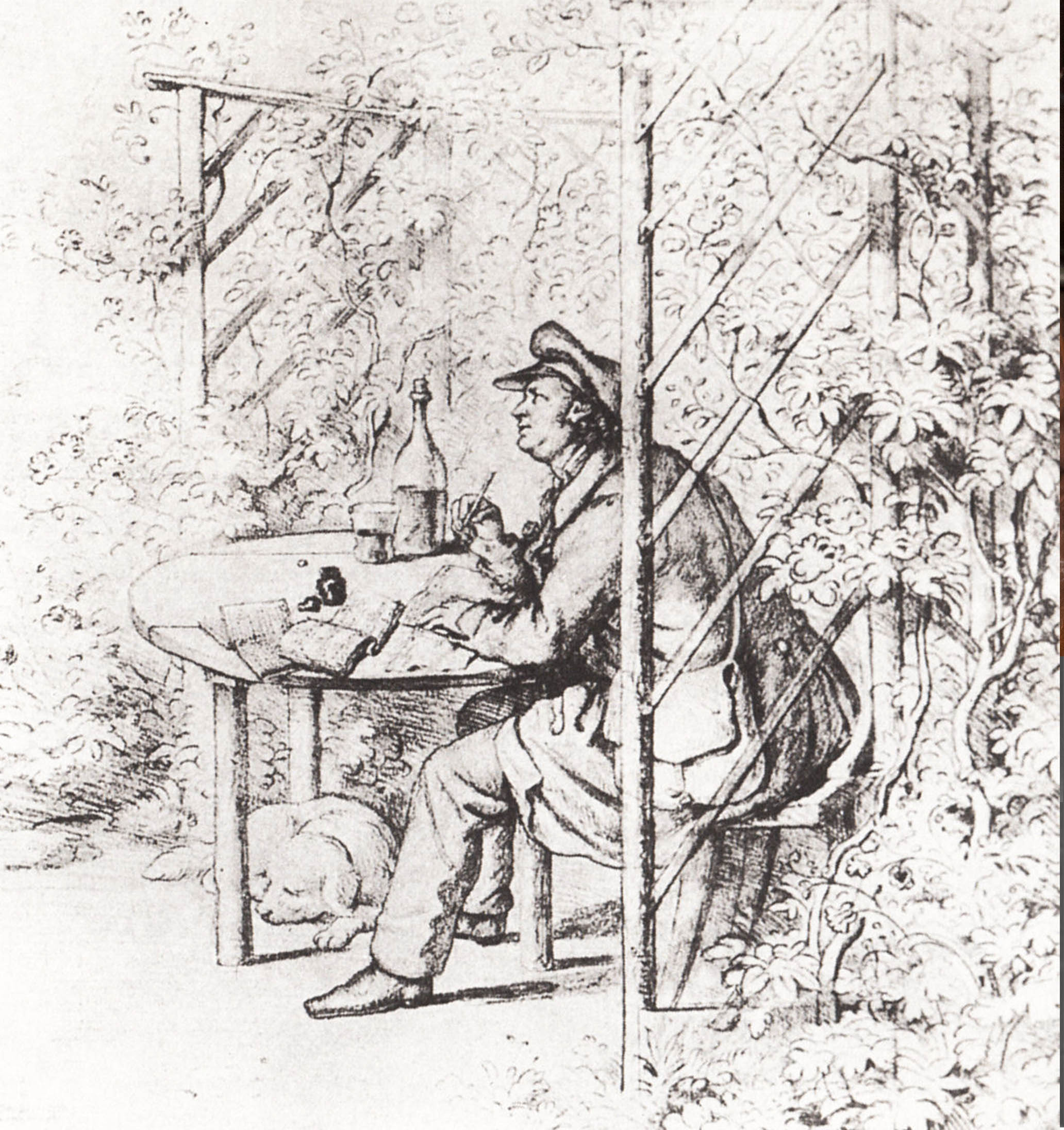

The “Jean Paul” to which Franz referred is the German author and philosopher Jean Paul Friedrich Richter (1763-1825). During his life, he was famous as an author of humorous and satirical novels, which were filled with dramatic contrasts of tone and style. Fittingly, his major philosophical work, School for Aesthetics (1804), is a study of humor. It is here that he introduces an interpretation of humor as “inverse sublimity.”2 If the romantic sublime is an attempt to represent the unrepresentable — the metaphysical, the ideal, the world of inexpressible emotions and ideas — then its inverse, humor, is a juxtaposition of the sublime with our finite and imperfect real world. The real world is shown to be wanting, but through this failure, some truth about the incomprehensible sublime is revealed. - (Ernst Joachim Förster, “Jean Paul in his garden in Bayreuth”, c. 1826)

The “Jean Paul” to which Franz referred is the German author and philosopher Jean Paul Friedrich Richter (1763-1825). During his life, he was famous as an author of humorous and satirical novels, which were filled with dramatic contrasts of tone and style. Fittingly, his major philosophical work, School for Aesthetics (1804), is a study of humor. It is here that he introduces an interpretation of humor as “inverse sublimity.”2 If the romantic sublime is an attempt to represent the unrepresentable — the metaphysical, the ideal, the world of inexpressible emotions and ideas — then its inverse, humor, is a juxtaposition of the sublime with our finite and imperfect real world. The real world is shown to be wanting, but through this failure, some truth about the incomprehensible sublime is revealed. - (Ernst Joachim Förster, “Jean Paul in his garden in Bayreuth”, c. 1826)

As Franz described, Beethoven paired the dark, serious, and foreboding slow opening with a spirited, high-octane main section. Like one of Jean-Paul’s novels, this section is dominated by quick shifts in mood and dynamics and, delights in exaggeration. The stark contrast created by this juxtaposition is comic: The opening’s sublime searching reveals nothing like the wrenching internal struggle of the Fifth or the world-conquering heroism of the Third, but, rather, it is music that seems apt for the overture to a comic farce. Beethoven seems to present a humorous counterargument to the earnest seriousness and intensity of works such as the Eroica. As we’ll see, he continues this counterargument in the remaining movements of this symphony.

Caspar David Friedrich, “The wanderer above the sea of fog,” 1812. Although this painting, one of the most emblematic of nineteenth-century romanticism, is not a depiction of the Archangel Michael, the wanderer’s lonely gaze, his high stature, and the threshold of fog make this a good depiction of Berlioz’s remarks.

Caspar David Friedrich, “The wanderer above the sea of fog,” 1812. Although this painting, one of the most emblematic of nineteenth-century romanticism, is not a depiction of the Archangel Michael, the wanderer’s lonely gaze, his high stature, and the threshold of fog make this a good depiction of Berlioz’s remarks.

Berlioz’s flowery description of the second movement is a good counterpoint to that provided by Franz. Although both focus on different aspects – Berlioz on the wistful, long-breathed melody, and Franz on the connections to ideas of freedom and heroism present in other works by Beethoven – both perceive the movement as in the midst of a symphony that otherwise is devoted to humor. Perhaps this movement provides a contrast to the remaining movements of the symphony, which helps throw the overall theme into sharper relief. Or, perhaps, through its mixture of slow lyricism and an insistent rhythm it offers another alternative to Beethoven’s more bombastic “heroic” style. Whichever and whatever it is, Beethoven leaves it for you to decide. Listen below and see what you think.

Beethoven Symphony No. 4, II. Adagio

The Cleveland Orchestra, Lorin Maazel

Archival Recording: Palacio de Bellas Artes, Mexico City, September 1, 1977

The remaining two movements of the symphony return to a frantic, comic tone. In the spirit of Richter’s concept of humor, they might be a reminder, after the second movement’s extended sojourn in sublimity, that joy and freedom are not achieved through serious and sorrowful music alone. The third and fourth movements revel in speed, exaggeration, and mock rhetoric.

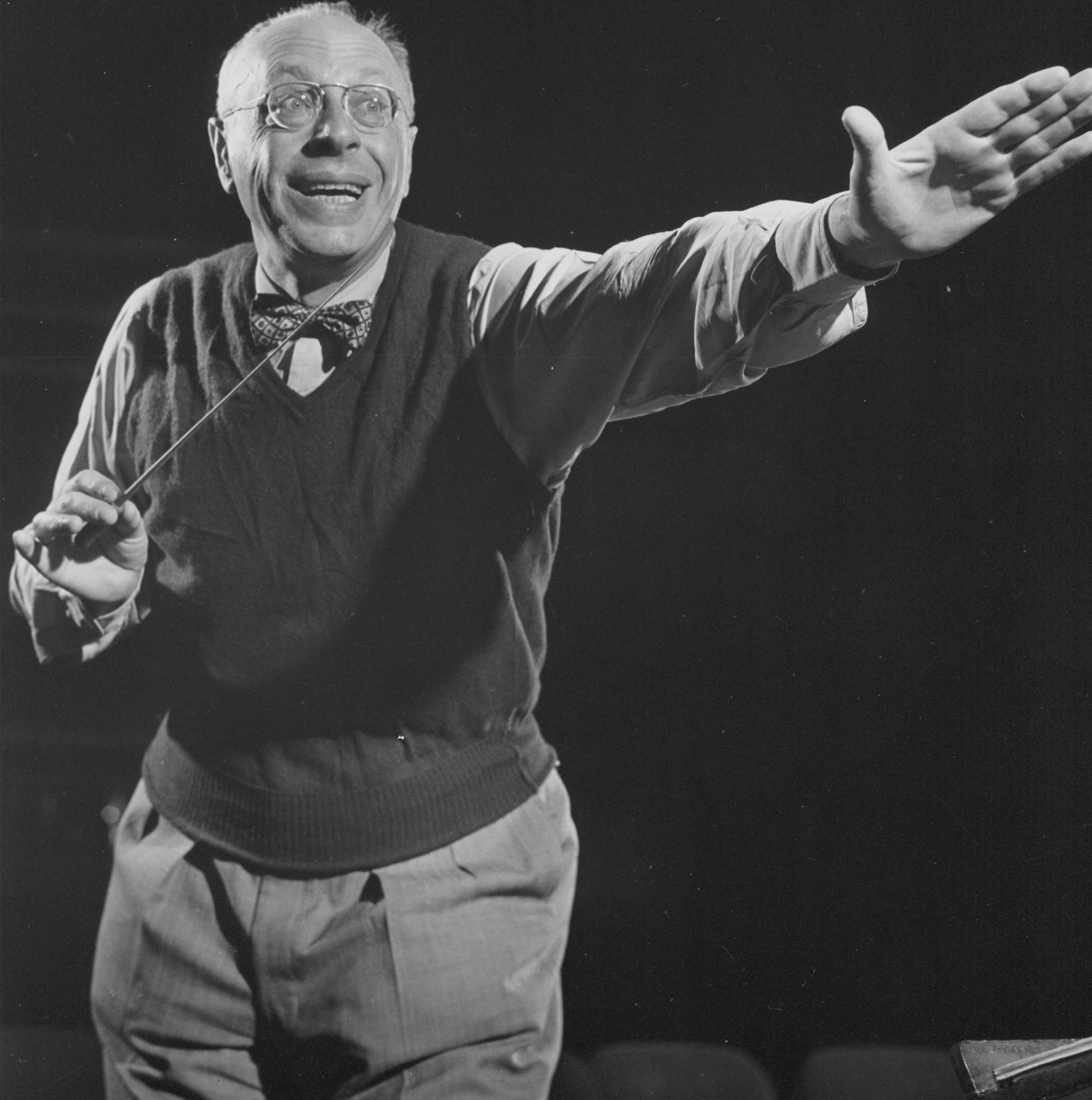

George Szell in rehearsal during his first season as Music Director, Severance Hall, November 8, 1947. In contrast to his more severe public image, this photo shows Szell in a light-hearted mood, much like the Fourth Symphony. Photograph by Geoffrey Landesman.

Beethoven Symphony No. 4, III. Allegro vivace

George Szell in rehearsal during his first season as Music Director, Severance Hall, November 8, 1947. In contrast to his more severe public image, this photo shows Szell in a light-hearted mood, much like the Fourth Symphony. Photograph by Geoffrey Landesman.

Beethoven Symphony No. 4, III. Allegro vivace

The Cleveland Orchestra, George Szell

Recorded: April 22, 1947

Released: Epic (Columbia), 1947

Jahja Ling, like Louis Lane before him, had a lengthy career with the Orchestra (Resident Conductor 1985-2002, Music Director of the Blossom Festival (2000-2005). In this photo he is conducting the Orchestra at Blossom, circa summer 2004. Photograph by Roger Mastrioanni.

Beethoven Symphony No. 4, IV. Allegro ma non troppo

Jahja Ling, like Louis Lane before him, had a lengthy career with the Orchestra (Resident Conductor 1985-2002, Music Director of the Blossom Festival (2000-2005). In this photo he is conducting the Orchestra at Blossom, circa summer 2004. Photograph by Roger Mastrioanni.

Beethoven Symphony No. 4, IV. Allegro ma non troppo

The Cleveland Orchestra, Jahja Ling

Archival Recording: Blossom Music Center, July 2, 1999

1 George Grove. Beethoven and his Nine Symphonies (London: Novello, 1896), 98; Lewis Lockwood. Beethoven’s Symphonies: An Artistic Vision (New York: Norton, 2017), 80.

2 Thomas Sipe. “Beethoven, Shakespeare, and the ‘Appassionata.’” In Beethoven Forum , Vol. 4, edited by Christopher Reynolds, Lewis Lockwood, and James Webster (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1995), 76.

3 Hector Berlioz. A Critical Study of Beethoven’s Nine Symphonies, translated by Edwin Evans (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 2000), 56.

Alexander Lawler

Alexander Lawler is a Historical Musicology PhD student at Case Western Reserve University. This is his third year working in the Orchestra’s Archives, having previously written “From the Archives” online essays (2015-2016) and designed a photo digitization and metadata project (2016-2017).

Symphony No. 8

The Eighth Symphony generally has been regarded as the slightest of Beethoven’s mature symphonies because of its short length, lighter tone, and frequent return to the musical styles and forms of the eighteenth century.

Read more >

Leonora Overture No. 3

Fidelio (1805), Beethoven’s only opera, is a celebration of freedom. In the opera, Florestan has been imprisoned by the tyrant Don Pizarro.

Read more >

Symphony No. 2

Beethoven first realized he was becoming deaf in the summer of 1798, at age twenty-seven. After an initial episode of total deafness, Beethoven found that his hearing had become filled with an unending “maddening chorus of squealing, buzzing, and humming.”

Read more >

Symphony No. 6

Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony premiered on the same concert as the Fifth Symphony (December 22, 1808). The two works were quite different: Whereas the Fifth was a difficult journey from darkness to light, the Pastoral was a genial, warm-hearted journey through the countryside.

Read more >

Grosse Fuge

The Grosse Fuge (Great Fugue) is Beethoven’s most complex work. It was originally to be the last movement of his String Quartet No. 13. However, it unluckily proved to be both technically challenging for the performers and bewildering to the audience, and was, instead, turned into its own stand-alone work.

Read more >

Symphony No. 9

Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony stands as the culmination of Beethoven’s twenty-four-year career as a composer of symphonies. The Ninth both sums up Beethoven’s artistic career and, with the choral finale, daringly points the way forward to new conceptions of what a symphony could say and be.

Read more >