Beethoven first realized he was becoming deaf in the summer of 1798, at age twenty-seven. After an initial episode of total deafness, Beethoven found that his hearing had become filled with an unending “maddening chorus of squealing, buzzing, and humming.”1 Initially, Beethoven told no one; he feared what others would do and think if they had known of his condition, fearing for his career as a musician. It was not until 1801 that Beethoven revealed his deafness to anyone in his circle (having written to his close friend Franz Wegeler). During these years, even at his lowest, Beethoven did not seem to believe he would lose his hearing completely, and be left with that “maddening chorus.” However, in the summer of 1802, as he composed his Second Symphony while in Heiligenstadt, he finally came to realize his fears were coming to pass.2

In Heiligenstadt, Beethoven may have first contemplated suicide. Here, in the countryside which Beethoven loved, he struggled mightily with the realization that he would become fully deaf, having spent years denying it to himself. In the Heiligenstadt Testament, written following his stay in the town, he described how experiences such as: “‘When someone standing next to me heard a flute in the distance and I heard nothing or someone heard a shepherd singing and again I heard nothing.’” It was these small experiences which brought him “‘close to despair’” and “‘at the point of ending [his] life.’” 3

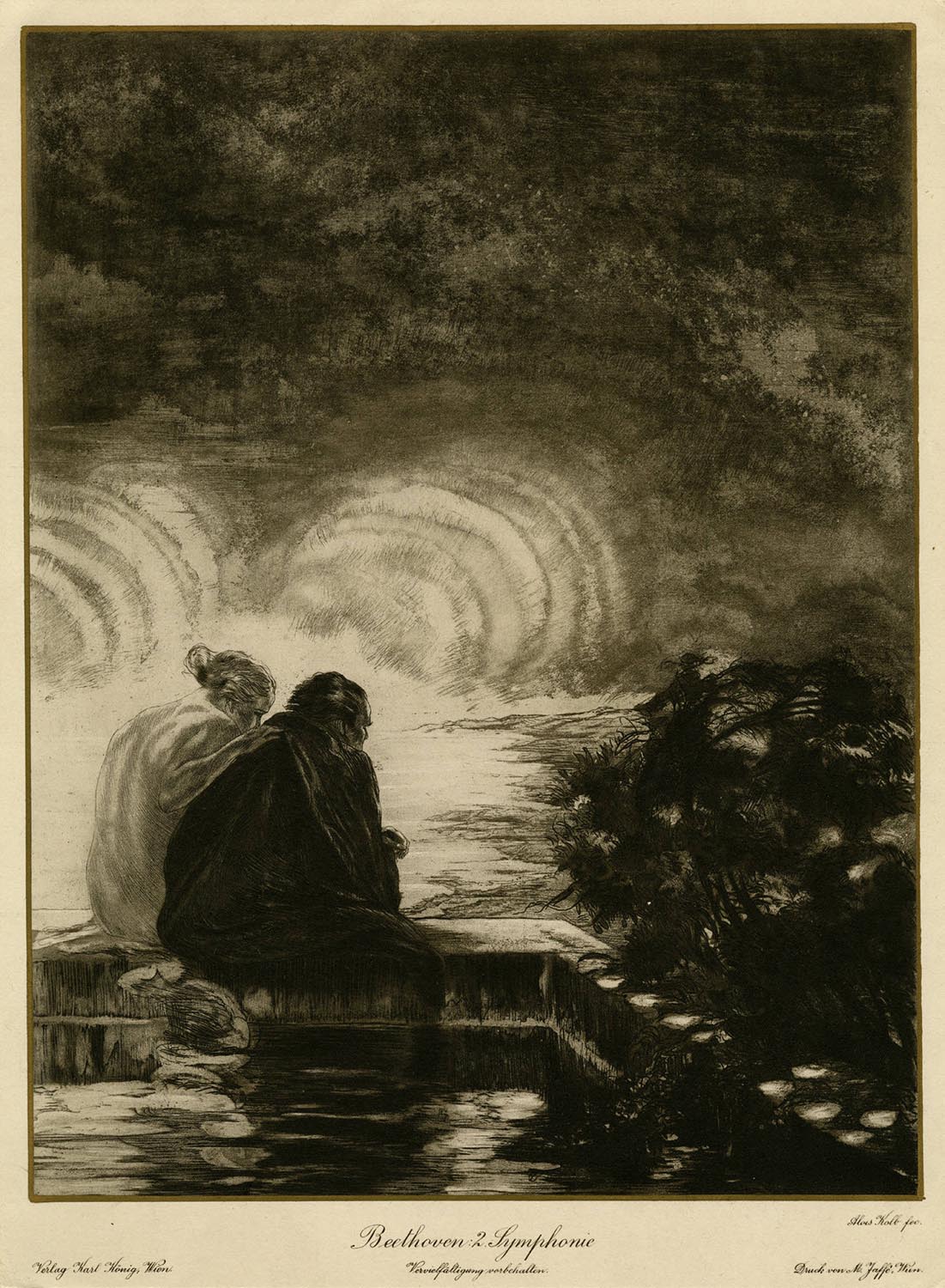

Second Symphony, by Alois Kolb (ca. 1921). From the collections of the Ira F. Brilliant Center for Beethoven Studies, San José State University.

Beethoven, Symphony No. 2, II. Larghetto

Second Symphony, by Alois Kolb (ca. 1921). From the collections of the Ira F. Brilliant Center for Beethoven Studies, San José State University.

Beethoven, Symphony No. 2, II. Larghetto

The Cleveland Orchestra, Franz Welser-Möst

Archival Recording: Severance Hall, January 20, 2004

“‘The only thing that held me back was my art.’”4 It is here that Beethoven begins to self-consciously embrace the path of Prometheus as the only way forward. Beethoven describes how, with a “‘soul. . . filled with a love for humanity and a desire to do good’” he did not wish to die before he could write as much music as he could. He “vowed to live with suffering and for his art,” as Beethoven biographer Jan Swafford describes.

Beethoven, Symphony No. 2, III. Scherzo: Allegro

The Cleveland Orchestra, Christoph von Dohnányi

Archival Recording: Severance Hall, September 23, 1993

Typically, scholars and critics have connected the Eroica, and not the Second Symphony, to the Heiligenstadt Testament; musicologist N. Straus traces this back to 1927.6 The Second Symphony has long been overshadowed because of ideas that Beethoven was “not supposed to be able to write vivacious and energetic works” during the same period that he was in “torment,” as noted by musicologist Lewis Lockwood.7 However, this symphony, with its “strongly mercurial emotional climate” and often upbeat spirit speaks to a powerful sense of hope and joy in the face of something threatening lurking in the background.8 Perhaps this symphony also embodies another facet of Beethoven’s response to his personal crisis: the hope and joy that Art can bring.

Beethoven, Symphony No. 2, IV. Allegro Molto

The Cleveland Orchestra, Pierre Boulez

Archival Recording: Severance Hall, November 24, 1967

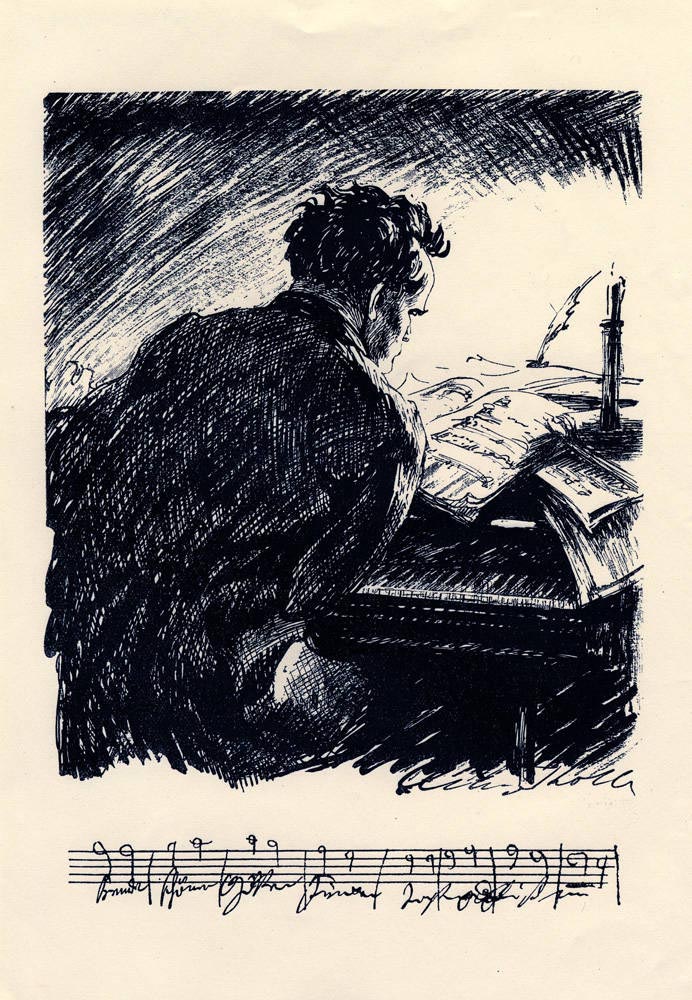

“Beethoven at the piano” by Alois Kolb (orig. 1921, this version 1927) - From the collections of the Ira F. Brilliant Center for Beethoven Studies, San José State University

“Beethoven at the piano” by Alois Kolb (orig. 1921, this version 1927) - From the collections of the Ira F. Brilliant Center for Beethoven Studies, San José State University

1 Jan Swafford, Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014), 224.

2 Swafford, Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph, 225, 275-276, 300.

3 Lewis Lockwood, Beethoven: The Music and the Life (New York: W.W. Norton, 2005), 119.

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Joseph N. Straus, Extraordinary Measures: Disability in Music (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 54; Straus himself offers a reading of the Eroica (among other works) in this vein (45-62).

7 Lewis Lockwood, Beethoven’s Symphonies: An Artistic Vision (New York: W.W. Norton, 2017), 40-41.

8 Lockwood, Beethoven’s Symphonies, 41.

Alexander Lawler is a Historical Musicology PhD student at Case Western Reserve University. This is his third year working in the Orchestra’s Archives, having previously written “From the Archives” online essays (2015-2016) and designed a photo digitization and metadata project (2016-2017).

Symphony No. 6

Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony premiered on the same concert as the Fifth Symphony (December 22, 1808). The two works were quite different: Whereas the Fifth was a difficult journey from darkness to light, the Pastoral was a genial, warm-hearted journey through the countryside.

Read more >

Grosse Fuge

The Grosse Fuge (Great Fugue) is Beethoven’s most complex work. It was originally to be the last movement of his String Quartet No. 13. However, it unluckily proved to be both technically challenging for the performers and bewildering to the audience, and was, instead, turned into its own stand-alone work.

Read more >

Symphony No. 9

Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony stands as the culmination of Beethoven’s twenty-four-year career as a composer of symphonies. The Ninth both sums up Beethoven’s artistic career and, with the choral finale, daringly points the way forward to new conceptions of what a symphony could say and be.

Read more >