The First Steps of a Symphonic Revolutionary

Beethoven: Symphony No. 1 in C Major (1800)

“There is something revolutionary in that music!”1

— Holy Roman Emperor Francis II on Beethoven’s music, c. late 1790s or early 1800s

This alleged remark by the reactionary Francis II on Beethoven’s music seems strange, coming as it does before Beethoven’s “Heroic Period” of the Third Symphony and thereafter. In the mainstream history of Beethoven, his early works are more classical in style, hewing close to Mozart and (especially) Haydn. A work such as his first symphony, his first venture into writing sonata form with a full symphony displays caution and a more conservative mode. This is, in part, due to our ears knowing Beethoven’s later symphonies. As scholar Donald Tovey describes, “The caution which seems so obvious to us was not noticed by his contemporary critics.”2 Indeed, contemporary critics highlighted virtually every one of Beethoven’s deviations from classical norms – from beginning his symphony in the wrong key to his overuse of the wind section, which can be heard in the first audio excerpt. What these criticisms clued into was that in his First Symphony, Beethoven was already transgressing his era’s conventional symphonic rhetoric. These transgressions, while only the beginning for Beethoven, sought a new manner of expression and represent an introduction to the idea of Beethoven as a promethean figure. This symphony is a harbinger of who Beethoven was and where he intended to go with his music.

Portrait of Beethoven (1800), engraved by Johann Neidl, based on a drawing by Gandolph Ernst Stainhauser von Treuberg. Portrait of Beethoven (1800), engraved by Johann Neidl, based on a drawing by Gandolph Ernst Stainhauser von Treuberg.

|

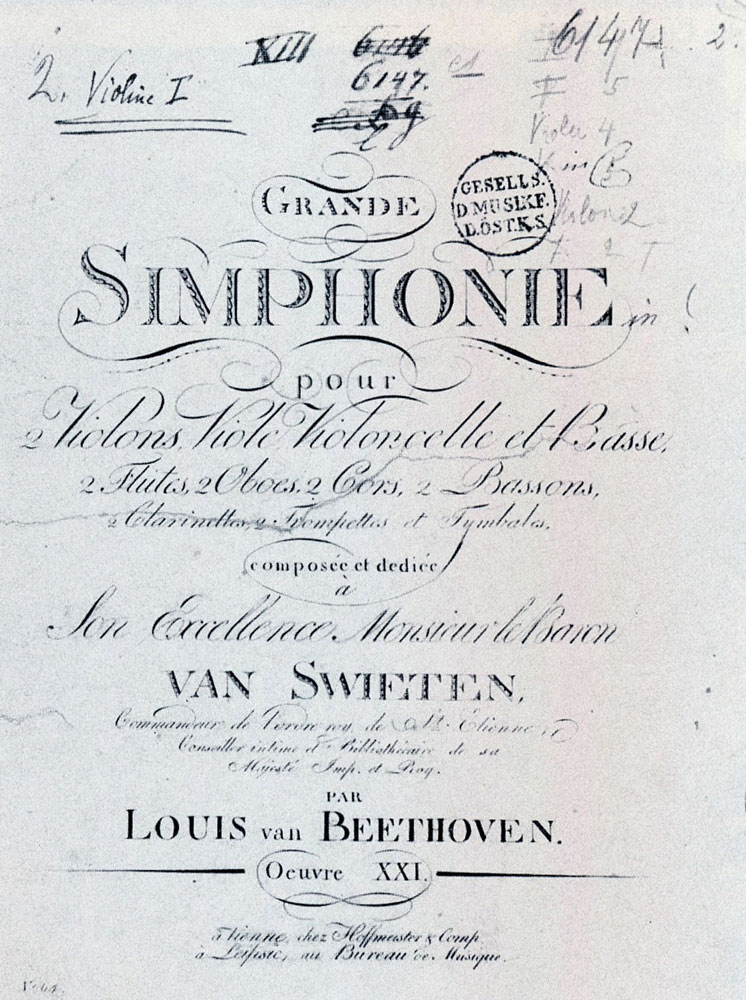

Title page to the first edition of Beethoven’s First Symphony (Vienna: Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, 1800). Title page to the first edition of Beethoven’s First Symphony (Vienna: Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde, 1800).

|

The third movement of Beethoven’s First Symphony offers one example of his incipient drive to push beyond the boundaries of convention. In the classical symphony before Beethoven, the third movement was often a minuet and trio. The minuet was a courtly, stately dance generally in a slower tempo with a typical triple meter. In the middle of the movement was the trio, a lighter and often airier section featuring a change in key and instrumentation. Haydn’s symphonies had minuets, Mozart’s symphonies had minuets, and none of Beethoven’s had them – save the first, but in name only. Beethoven’s minuet is fast — far too fast to dance a minuet to. The stately unfolding of a triple is replaced by a frenetic rush and the usual pattern of a strong first beat followed by two weaker ones is overcome by what feels like a torrent of only strong beats. The music’s mood is mercurial, with quicksilver changes in dynamics and texture.

The contrasting trio section’s attempt at a pastoral tone ultimately fails to subdue the movement’s immense forward momentum, and its gentle, repeated chords build to a triumphant finish. This movement is not a minuet, but something else altogether – a proto-scherzo. The term “scherzo” (Italian for “joke”) denoted a light-hearted piece of music with a quick tempo in triple meter. Although the scherzo predates Beethoven, it was Beethoven who seized the potential of including such a form in the symphony. Adaptable for comedy or terror, Beethoven’s scherzo would become integral parts of his later symphonies and would define the genre for the rest of the century.

Beethoven: Symphony No. 1, III: Menuetto: Allegro molto e vivace (excerpt)

The Cleveland Orchestra, Artur Rodzinski

Recorded December 28, 1941, Released Columbia Records, 1943.

This recording of the minuet section of the movement is taken from one of the Orchestra’s earlier commercial recordings and features as conductor Artur Rodzinski, the Orchestra’s second music director. Rodzinski, known primarily for his skill in the romantic and operatic repertoires, did not conduct a great deal of classical-era music during his tenure. Indeed, his 1943 Columbia recording of Beethoven’s first symphony was the only classical-era work he recorded with the Orchestra. This photo is of him and Moses Smith, a Columbia Records producer, listening to the playback of a prospective recording. Photographer unknown, 1939. Courtesy of The Cleveland Orchestra Archives.

This recording of the minuet section of the movement is taken from one of the Orchestra’s earlier commercial recordings and features as conductor Artur Rodzinski, the Orchestra’s second music director. Rodzinski, known primarily for his skill in the romantic and operatic repertoires, did not conduct a great deal of classical-era music during his tenure. Indeed, his 1943 Columbia recording of Beethoven’s first symphony was the only classical-era work he recorded with the Orchestra. This photo is of him and Moses Smith, a Columbia Records producer, listening to the playback of a prospective recording. Photographer unknown, 1939. Courtesy of The Cleveland Orchestra Archives.

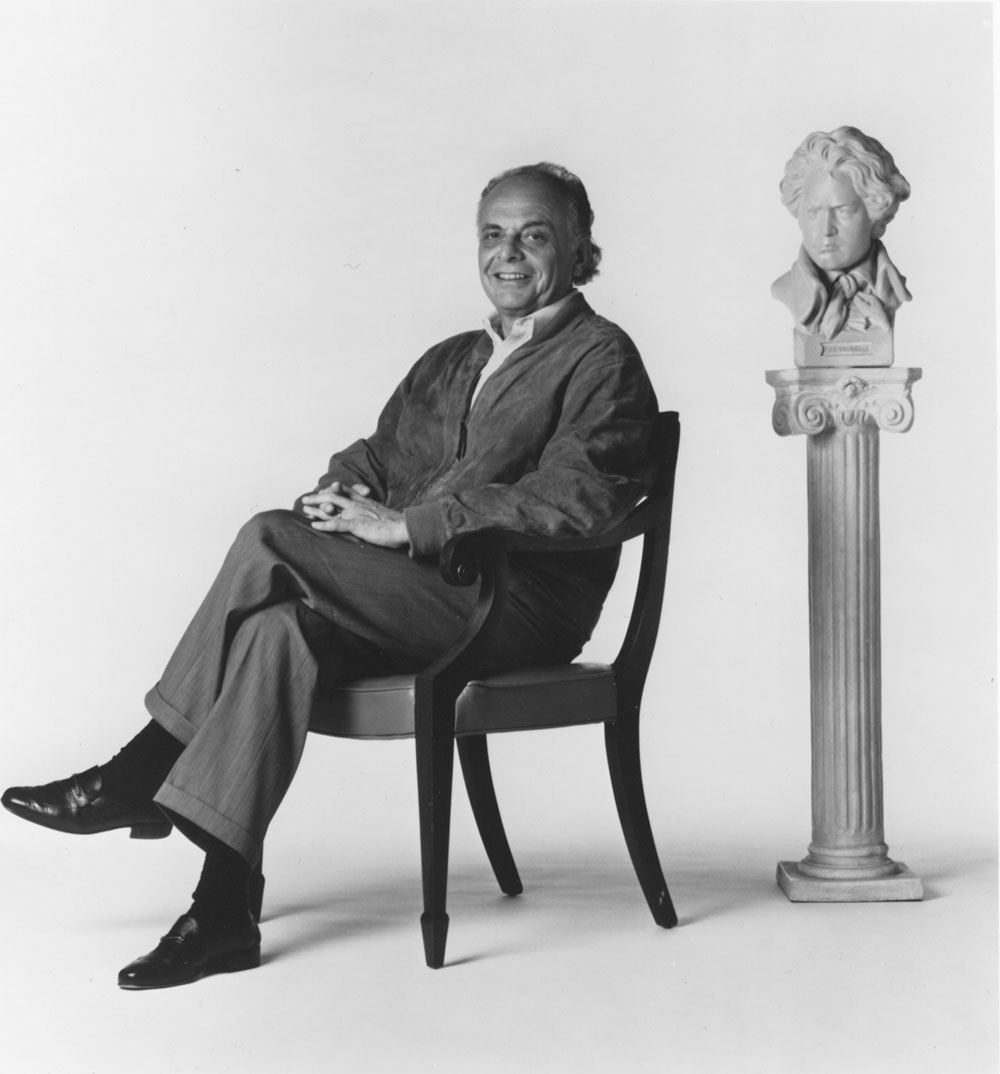

This recording of the trio section of the movement is taken from a commercial recording of Lorin Maazel’s 1979 Beethoven Cycle. Lorin Maazel was the Orchestra’s fifth music director (1970-1982) and was particularly fond of Beethoven. This, as well as Maazel’s idiosyncratic nature, are evidenced by Maazel’s liner notes to the cycle, which described Beethoven as “my friend.”

Beethoven: Symphony No. 1, III: Menuetto: Allegro molto e vivace (excerpt)

The Cleveland Orchestra, Lorin Maazel

Recorded April 29, 1978, Released CBS Masterworks, 1979.

This photograph shows Maazel (c. mid-1990s) posing with a bust of Beethoven. Photograph by Karen Meyers, date unknown.

This photograph shows Maazel (c. mid-1990s) posing with a bust of Beethoven. Photograph by Karen Meyers, date unknown.

However, it is the symphony’s fourth and final movement that most strongly foreshadows Beethoven’s later symphonies. Beethoven biographer Jan Swafford suggests that the fourth movement, which Beethoven composed last, “became the heaviest and most serious” and “pointed in the direction Beethoven was to pursue.”3 Music Director Franz Welser-Möst expands on this idea by highlighting how the movement grows from its unusual opening – a hesitant, slowly building upward scale in the violins. It is this “spark” from which the movement’s first theme emerges and infuses the entire movement.

1 Jan Swafford, Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph: A Biography (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014), 138.

2 Donald Francis Tovey, Symphonies and Other Orchestral Works: Selections from Essays in Musical Analysis (London: Oxford University Press, 1981), 36.

3 Swafford, Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph, 244.

Alexander Lawler

Alexander Lawler is a Historical Musicology PhD student at Case Western Reserve University. This is his third year working in the Orchestra’s Archives, having previously written “From the Archives” online essays (2015-2016) and designed a photo digitization and metadata project (2016-2017).

The Prometheus Project

As part of the Centennial Season’s celebration, Franz Welser-Möst has created “The Prometheus Festival,” examining Beethoven’s music through the metaphor of Prometheus.

Read more >

Overture to The Creatures of Prometheus

Perhaps the most overt example of Beethoven’s interaction with the idea of Prometheus was his only published ballet, The Creatures of Prometheus.

Read more >

Symphony No. 1

In the mainstream history of Beethoven, his early works are more classical in style, hewing close to Mozart and (especially) Haydn.

Read more >

Symphony No. 3

Beethoven’s Third Symphony, the Eroica, or “Heroic,” is one of the most influential pieces of music in history.

Read more >

Egmont Overture

Beethoven’s Egmont Overture is one of his many concert overtures depicting different kinds of heroic individuals.

Read more >

Symphony No. 4

Beethoven’s Fourth Symphony seems an anomaly compared to the heroic Third and the fateful Fifth.

Read more >

Symphony No. 7

In the Seventh, Beethoven suffuses each movement with a unique and persistent rhythmic pattern.

Read more >

Overture to Coriolan

Beethoven’s Overture to Coriolan is the only tragic piece in our Prometheus Festival. Indeed, in spite of the intense conflict that marks much of his music, Beethoven was something of an optimist

Read more >

Symphony No. 5

Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony is so familiar to us now that it might be difficult to imagine it as shocking or difficult.

Read more >

Symphony No. 8

The Eighth Symphony generally has been regarded as the slightest of Beethoven’s mature symphonies because of its short length, lighter tone, and frequent return to the musical styles and forms of the eighteenth century.

Read more >

Leonora Overture No. 3

Fidelio (1805), Beethoven’s only opera, is a celebration of freedom. In the opera, Florestan has been imprisoned by the tyrant Don Pizarro.

Read more >

Symphony No. 2

Beethoven first realized he was becoming deaf in the summer of 1798, at age twenty-seven. After an initial episode of total deafness, Beethoven found that his hearing had become filled with an unending “maddening chorus of squealing, buzzing, and humming.”

Read more >

Symphony No. 6

Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony premiered on the same concert as the Fifth Symphony (December 22, 1808). The two works were quite different: Whereas the Fifth was a difficult journey from darkness to light, the Pastoral was a genial, warm-hearted journey through the countryside.

Read more >

Grosse Fuge

The Grosse Fuge (Great Fugue) is Beethoven’s most complex work. It was originally to be the last movement of his String Quartet No. 13. However, it unluckily proved to be both technically challenging for the performers and bewildering to the audience, and was, instead, turned into its own stand-alone work.

Read more >

Symphony No. 9

Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony stands as the culmination of Beethoven’s twenty-four-year career as a composer of symphonies. The Ninth both sums up Beethoven’s artistic career and, with the choral finale, daringly points the way forward to new conceptions of what a symphony could say and be.

Read more >