Prometheus’s Prelude

Overture to The Creatures of Prometheus

By Alexander Lawler

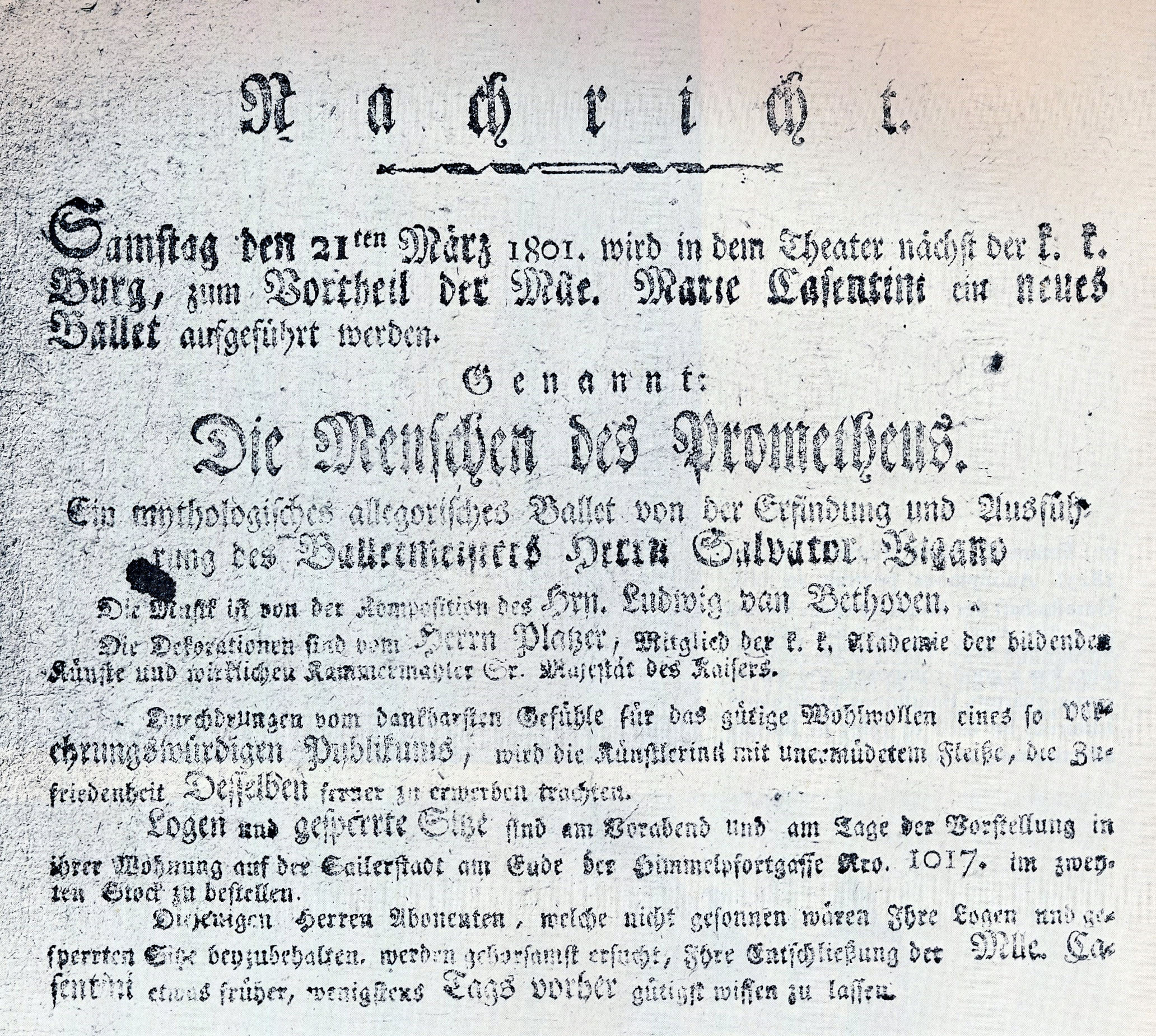

Perhaps the most overt example of Beethoven’s interaction with the idea of Prometheus was his only published ballet, The Creatures of Prometheus. This ballet was the fruit of a collaboration between him and Salvatore Viganò, Vienna court ballet master and fellow artistic progressive. Viganò’s adaption of the Prometheus myth for Beethoven’s ballet was based on a French Enlightenment-era retelling that cast Prometheus as both the creator of humanity and its guide in becoming truly human through the power of the performing arts.

Prometheus was the last of the Titans in Greek mythology. He sided with the younger upstart gods, led by Zeus, in their war against the Titans. After this war, Prometheus showed sympathy with, and loyalty to, another downtrodden group, humanity. To aid them, Prometheus shared the secrets of fire so that they might raise themselves up from the earth like the gods. The myth differs in each telling — some have Prometheus sharing other secrets, such as art or metalworking, and some, that Zeus took away fire from the humans and Prometheus stole it back for humanity — but virtually all agree that it was the fire of Prometheus that illuminated humanity and allowed civilization to develop.

The connection between Prometheus and Beethoven’s overture to The Creatures of Prometheus is not programmatic, but is instead abstract and philosophical. Two aspects of the overture, as highlighted by musicologist Paul Bertagnolli, contribute to this interpretation. The first is found in the overture’s opening chords, as can be heard in this audio clip. Beethoven violates orthodox harmonic practice by starting the overture with a sequence of chords that harmonize a different key than the rest of the overture. This “transgression” against the old musical order mirrors that of Prometheus against the gods. The second is the energetic theme that Beethoven introduces in the faster allegro section. This theme prefigures the main theme used for joyful conclusion of the ballet, in which the “creatures of Prometheus” have attained true “animation through the power of the arts.”1 These two features, as well as the overture’s high spirits, help connect the overture to the ballet’s uplifting Promethean ideal.

Beethoven: Overture to The Creatures of Prometheus

The Cleveland Orchestra, Louis Lane

Archival Recording: Severance Hall, June 28, 1966

This archival recording was taken from “Violins of Hope,” a special concert on September 27, 2015 by The Cleveland Orchestra that marked the opening of the Maltz Performing Arts Center. Central to the event were the titular violins: violins played by Jews in the concentration camps, now restored and able to freely sing. Photograph by Roger Mastroianni, 2015. Courtesy of The Cleveland Orchestra Archives.

- 1 Paul Bertagnolli, Prometheus in Music: Representations of the Myth in the Romantic Era (New York: Routledge, 2007, 2016), 36-38.

- Alexander Lawler worked for the Orchestra’s Archives over three seasons while working on a Historical Musicology PhD at Case Western Reserve University. First writing the “From the Archives” online essays in the 2015/16 season, next designing a photo digitization and metadata project in the 2016/17 season and finally, in the 2017/18 centennial season with the Prometheus Project.

Essay & Audio Library

Beethoven: The Prometheus Connection

In 1812, Ludwig van Beethoven received a letter from a young pianist named Emilie M. Her letter, enclosed with a home-made embroidered pocketbook, expressed her fondness for, and appreciation of, his music.

Continue Reading

Overture to The Creatures of Prometheus

1801

Perhaps the most overt example of Beethoven’s interaction with the idea of Prometheus was his only published ballet, The Creatures of Prometheus.

Continue Reading

Leonora Overture No. 3

1806

Fidelio (1805), Beethoven’s only opera, is a celebration of freedom. In the opera, Florestan has been imprisoned by the tyrant Don Pizarro.

Continue Reading

Overture to Coriolan

1807

Beethoven’s Overture to Coriolan is the only tragic piece in our Prometheus Festival. Indeed, in spite of the intense conflict that marks much of his music, Beethoven was something of an optimist.

Continue Reading

Egmont Overture

1810

Beethoven’s Egmont Overture is one of his many concert overtures depicting different kinds of heroic individuals.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 1

1800

In the mainstream history of Beethoven, his early works are more classical in style, hewing close to Mozart and (especially) Haydn.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 2

1802

Beethoven first realized he was becoming deaf in the summer of 1798, at age twenty-seven. After an initial episode of total deafness, Beethoven found that his hearing had become filled with an unending “maddening chorus of squealing, buzzing, and humming.”

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 3

1804

Beethoven’s Third Symphony, the Eroica, or “Heroic,” is one of the most influential pieces of music in history.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 4

1806

Beethoven’s Fourth Symphony seems an anomaly compared to the heroic Third and the fateful Fifth.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 5

1808

Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony is so familiar to us now that it might be difficult to imagine it as shocking or difficult.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 6

1808

Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony premiered on the same concert as the Fifth Symphony (December 22, 1808). The two works were quite different: Whereas the Fifth was a difficult journey from darkness to light, the Pastoral was a genial, warm-hearted journey through the countryside.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 7

1812

In the Seventh, Beethoven suffuses each movement with a unique and persistent rhythmic pattern.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 8

1812

The Eighth Symphony generally has been regarded as the slightest of Beethoven’s mature symphonies because of its short length, lighter tone, and frequent return to the musical styles and forms of the eighteenth century.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 9

1824

Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony stands as the culmination of Beethoven’s twenty-four-year career as a composer of symphonies.

Continue Reading

Grosse Fuge

1825

The Grosse Fuge (Great Fugue) is Beethoven’s most complex work. It was originally to be the last movement of his String Quartet No. 13. However, it unluckily proved to be both technically challenging for the performers and bewildering to the audience, and was, instead, turned into its own stand-alone work.

Continue Reading