Fear No More

Beethoven's Egmont Overture (1810)

By Alexander Lawler

Beethoven’s Egmont Overture is one of his many concert overtures depicting different kinds of heroic individuals. The Egmont Overture is derived from the incidental music Beethoven wrote for Goethe’s play of the same name (Egmont, 1788). The play is a historical drama of the sixteenth-century struggle of the Count of Egmont against the Duke of Alba for the freedom of the Netherlands. In the play, Egmont boldly confronts Alba’s tyranny, knowing that it will cost him his life. His sacrifice is not in vain: it will ensure the downfall of Alba. Beethoven condenses one of the primary messages of Goethe’s play into a searing overture: the only way to defeat tyranny is through an equally strong gesture of defiance, although such an act carries with it great peril. Egmont resembles Prometheus, whose resistance to tyranny through his theft of fire led to his imprisonment, but also humanity’s salvation. However, this connection goes farther, as Franz Welser-Möst describes below:

Franz discusses examples of promethean heroes and the difficulty of freedom. Features an excerpt of the Orchestra’s 60th Anniversary TV Special (1978), with Lorin Maazel conducting a performance of Beethoven’s Egmont Overture. Video compiled and edited by Alexander Lawler. All audio, images, and pictures courtesy of The Cleveland Orchestra Archives.

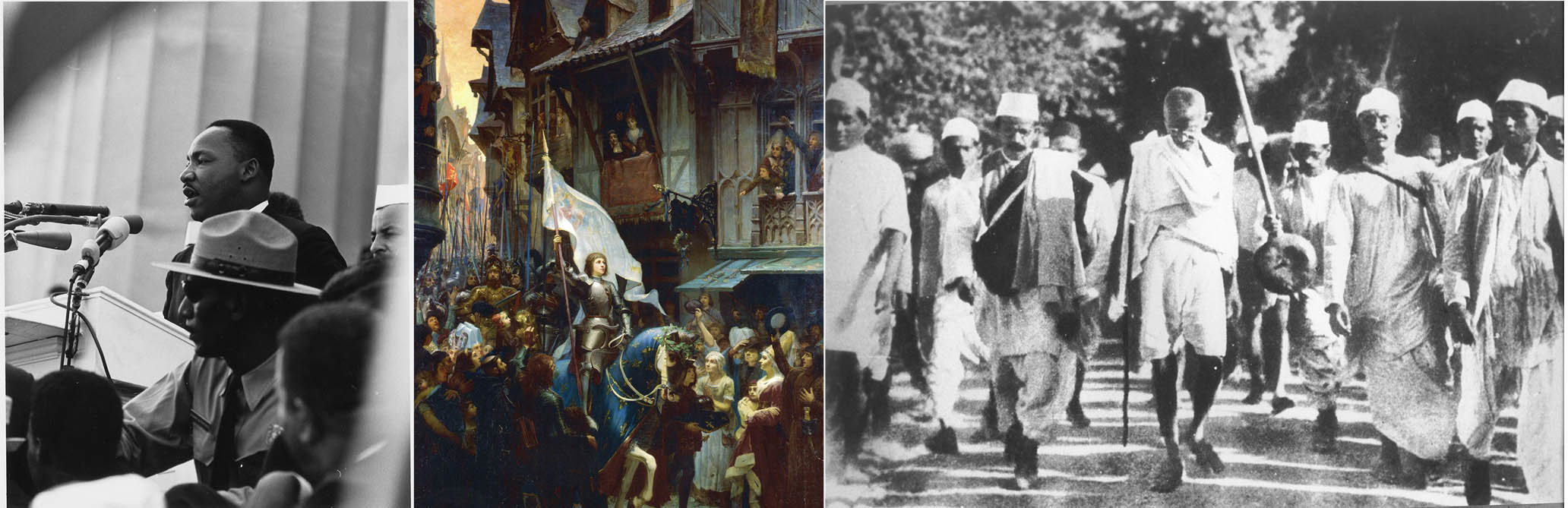

Franz describes another aspect of being a promethean hero, – the ability to conquer fear. To stand up against tyranny and the status quo is difficult and frightening. Any act of resistance requires that one defeat fear doubly — in standing up to tyranny and facing the unknown consequences. Promethean figures like Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr, Mahatma Gandhi, Joan of Arc, and Egmont stood up and, through their heroism, and sacrifice, gave others the strength to stand. Although they ultimately lost their lives in pursuit of freedom (just as in the stirring conclusion to the Egmont Overture), the fire that their heroic spark started would become a blaze.

You can listen below to the rest of Egmont’s promethean journey — conflict, hope, despair, and salvation — through a selection of audio clips from the Orchestra archives.

Beethoven: Egmont Overture – Part 2

The Cleveland Orchestra, Louis Lane

Archival Recording: Severance Hall, December 8, 1967

Beethoven: Egmont Overture – Part 3

The Cleveland Orchestra, George Szell

Archival Recording: Blossom Music Center, July 20, 1968

Beethoven: Egmont Overture – Part 4

The Cleveland Orchestra, Franz Welser-Möst

Archival Recording: Severance Hall, July 14, 2017

- Alexander Lawler worked for the Orchestra’s Archives over three seasons while working on a Historical Musicology PhD at Case Western Reserve University. First writing the “From the Archives” online essays in the 2015/16 season, next designing a photo digitization and metadata project in the 2016/17 season and finally, in the 2017/18 centennial season with the Prometheus Project.

Essay & Audio Library

Beethoven: The Prometheus Connection

In 1812, Ludwig van Beethoven received a letter from a young pianist named Emilie M. Her letter, enclosed with a home-made embroidered pocketbook, expressed her fondness for, and appreciation of, his music.

Continue Reading

Overture to The Creatures of Prometheus

1801

Perhaps the most overt example of Beethoven’s interaction with the idea of Prometheus was his only published ballet, The Creatures of Prometheus.

Continue Reading

Leonora Overture No. 3

1806

Fidelio (1805), Beethoven’s only opera, is a celebration of freedom. In the opera, Florestan has been imprisoned by the tyrant Don Pizarro.

Continue Reading

Overture to Coriolan

1807

Beethoven’s Overture to Coriolan is the only tragic piece in our Prometheus Festival. Indeed, in spite of the intense conflict that marks much of his music, Beethoven was something of an optimist.

Continue Reading

Egmont Overture

1810

Beethoven’s Egmont Overture is one of his many concert overtures depicting different kinds of heroic individuals.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 1

1800

In the mainstream history of Beethoven, his early works are more classical in style, hewing close to Mozart and (especially) Haydn.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 2

1802

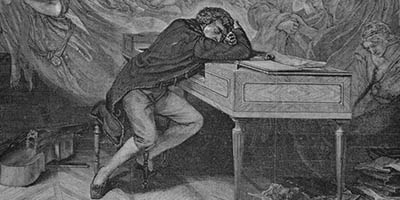

Beethoven first realized he was becoming deaf in the summer of 1798, at age twenty-seven. After an initial episode of total deafness, Beethoven found that his hearing had become filled with an unending “maddening chorus of squealing, buzzing, and humming.”

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 3

1804

Beethoven’s Third Symphony, the Eroica, or “Heroic,” is one of the most influential pieces of music in history.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 4

1806

Beethoven’s Fourth Symphony seems an anomaly compared to the heroic Third and the fateful Fifth.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 5

1808

Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony is so familiar to us now that it might be difficult to imagine it as shocking or difficult.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 6

1808

Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony premiered on the same concert as the Fifth Symphony (December 22, 1808). The two works were quite different: Whereas the Fifth was a difficult journey from darkness to light, the Pastoral was a genial, warm-hearted journey through the countryside.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 7

1812

In the Seventh, Beethoven suffuses each movement with a unique and persistent rhythmic pattern.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 8

1812

The Eighth Symphony generally has been regarded as the slightest of Beethoven’s mature symphonies because of its short length, lighter tone, and frequent return to the musical styles and forms of the eighteenth century.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 9

1824

Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony stands as the culmination of Beethoven’s twenty-four-year career as a composer of symphonies.

Continue Reading

Grosse Fuge

1825

The Grosse Fuge (Great Fugue) is Beethoven’s most complex work. It was originally to be the last movement of his String Quartet No. 13. However, it unluckily proved to be both technically challenging for the performers and bewildering to the audience, and was, instead, turned into its own stand-alone work.

Continue Reading