I, Prometheus:

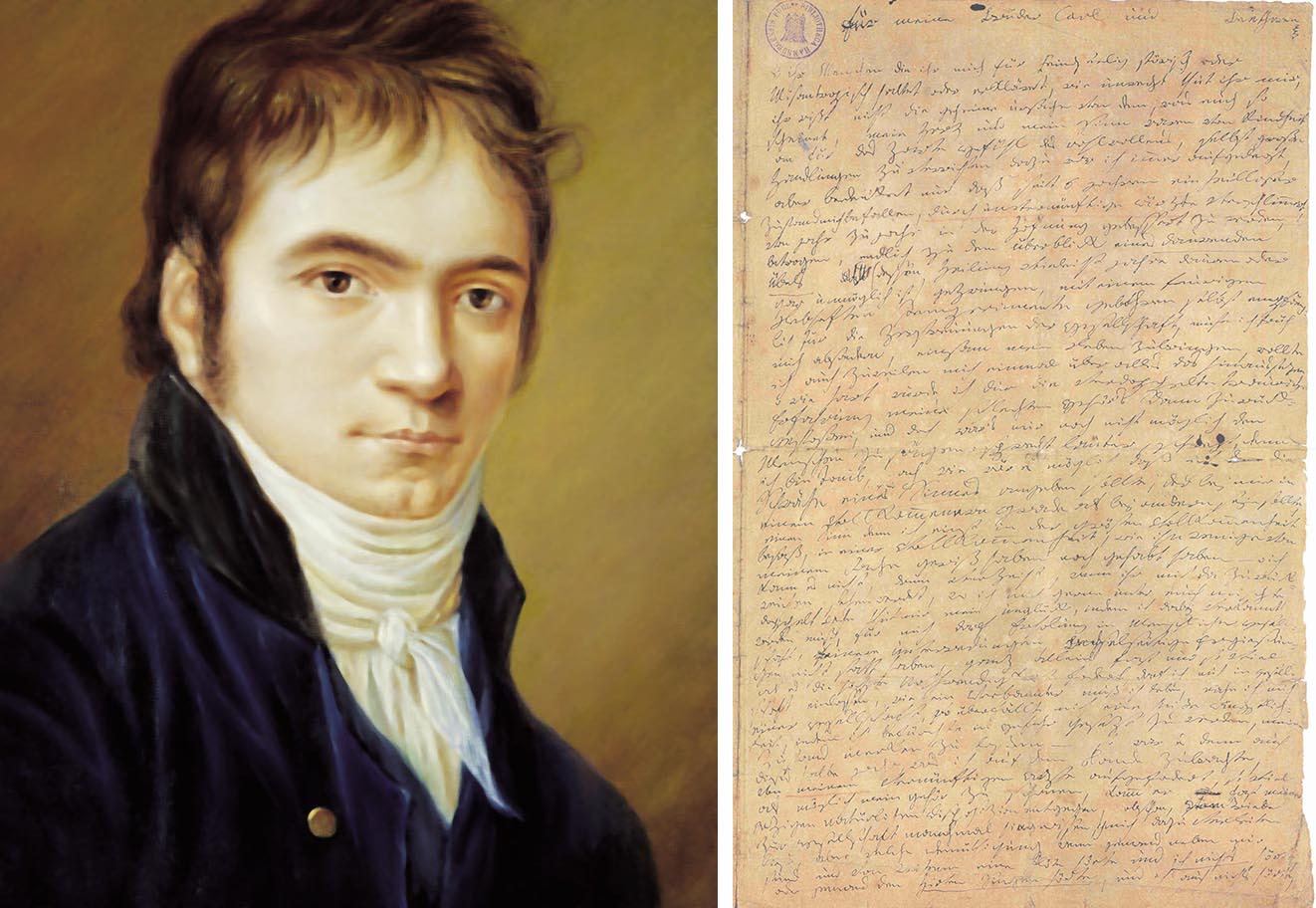

Beethoven's Symphony No. 2 in D Major (1802)

By Alexander Lawler

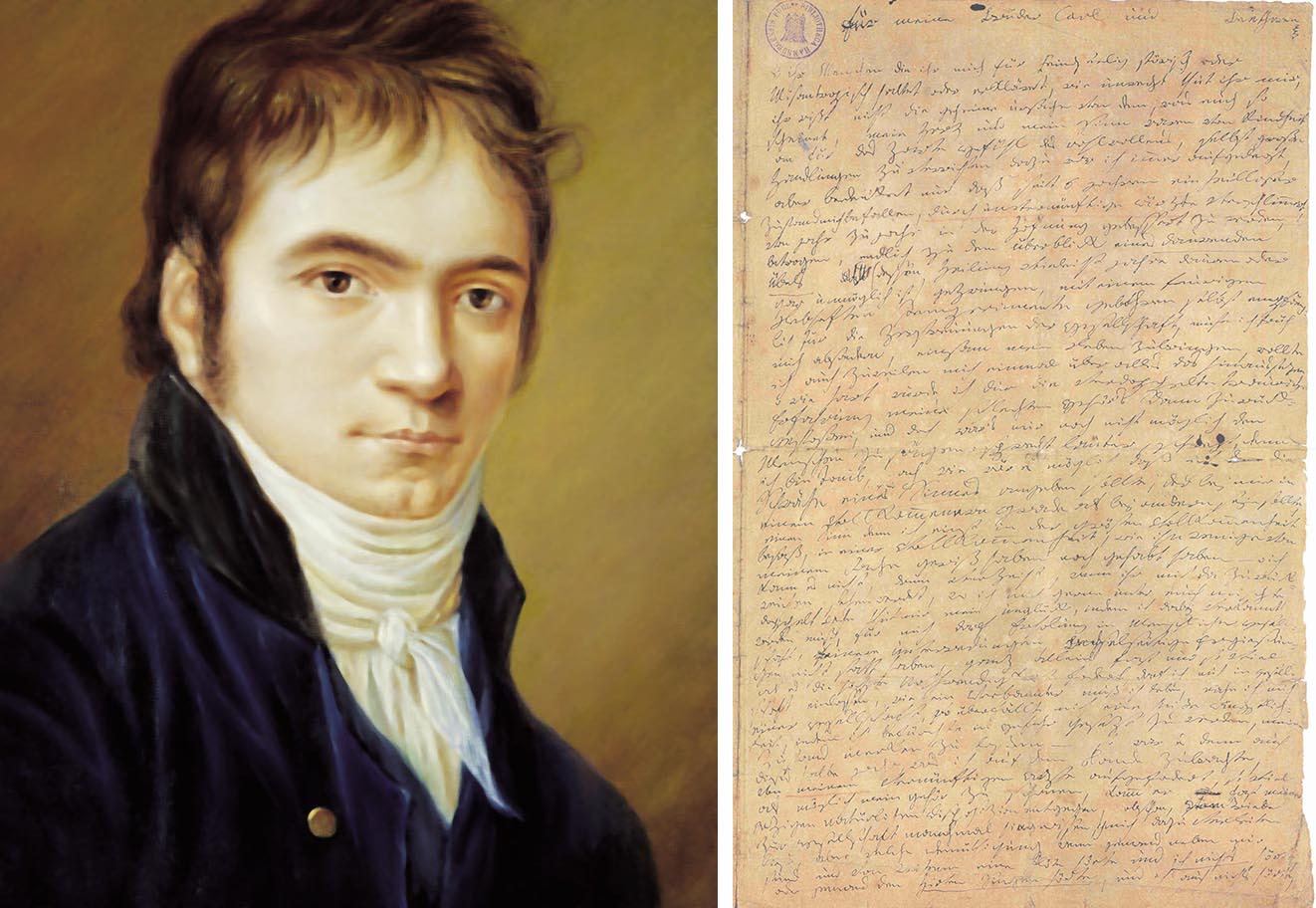

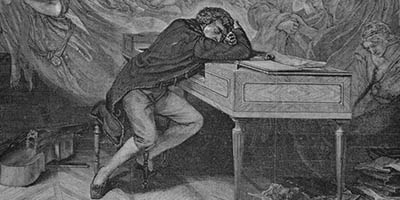

Beethoven first realized he was becoming deaf in the summer of 1798, at age twenty-seven. After an initial episode of total deafness, Beethoven found that his hearing had become filled with an unending “maddening chorus of squealing, buzzing, and humming.”1 Initially, Beethoven told no one; he feared what others would do and think if they had known of his condition, fearing for his career as a musician. It was not until 1801 that Beethoven revealed his deafness to anyone in his circle (having written to his close friend Franz Wegeler). During these years, even at his lowest, Beethoven did not seem to believe he would lose his hearing completely, and be left with that “maddening chorus.” However, in the summer of 1802, as he composed his Second Symphony while in Heiligenstadt, he finally came to realize his fears were coming to pass.2

In Heiligenstadt, Beethoven may have first contemplated suicide. Here, in the countryside which Beethoven loved, he struggled mightily with the realization that he would become fully deaf, having spent years denying it to himself. In the Heiligenstadt Testament, written following his stay in the town, he described how experiences such as: “‘When someone standing next to me heard a flute in the distance and I heard nothing or someone heard a shepherd singing and again I heard nothing.’” It was these small experiences which brought him “‘close to despair’” and “‘at the point of ending [his] life.’” 3

“The only thing that held me back was my art.”

— Ludwig van Beethoven4

It is here that Beethoven begins to self-consciously embrace the path of Prometheus as the only way forward. Beethoven describes how, with a “‘soul. . . filled with a love for humanity and a desire to do good’” he did not wish to die before he could write as much music as he could. He “vowed to live with suffering and for his art,” as Beethoven biographer Jan Swafford describes.5

Typically, scholars and critics have connected the Eroica, and not the Second Symphony, to the Heiligenstadt Testament; musicologist N. Straus traces this back to 1927.6The Second Symphony has long been overshadowed because of ideas that Beethoven was “not supposed to be able to write vivacious and energetic works” during the same period that he was in “torment,” as noted by musicologist Lewis Lockwood.7 However, this symphony, with its “strongly mercurial emotional climate” and often upbeat spirit speaks to a powerful sense of hope and joy in the face of something threatening lurking in the background.8 Perhaps this symphony also embodies another facet of Beethoven’s response to his personal crisis: the hope and joy that Art can bring.

- 1 Jan Swafford, Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2014), 224.

- 2 Swafford, Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph, 225, 275-276, 300.

- 3 MLewis Lockwood, Beethoven: The Music and the Life (New York: W.W. Norton, 2005), 119.

- 4 Ibid.

- 5 Ibid.

- 6 Joseph N. Straus, Extraordinary Measures: Disability in Music (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011), 54; Straus himself offers a reading of the Eroica (among other works) in this vein (45-62).

- 7 Lewis Lockwood, Beethoven’s Symphonies: An Artistic Vision (New York: W.W. Norton, 2017), 40-41.

- 8 Lockwood, Beethoven’s Symphonies, 41.

- Alexander Lawler worked for the Orchestra’s Archives over three seasons while working on a Historical Musicology PhD at Case Western Reserve University. First writing the “From the Archives” online essays in the 2015/16 season, next designing a photo digitization and metadata project in the 2016/17 season, and finally, in the 2017/18 centennial season with the Prometheus Project.

Essay & Audio Library

Beethoven: The Prometheus Connection

In 1812, Ludwig van Beethoven received a letter from a young pianist named Emilie M. Her letter, enclosed with a home-made embroidered pocketbook, expressed her fondness for, and appreciation of, his music.

Continue Reading

Overture to The Creatures of Prometheus

1801

Perhaps the most overt example of Beethoven’s interaction with the idea of Prometheus was his only published ballet, The Creatures of Prometheus.

Continue Reading

Leonora Overture No. 3

1806

Fidelio (1805), Beethoven’s only opera, is a celebration of freedom. In the opera, Florestan has been imprisoned by the tyrant Don Pizarro.

Continue Reading

Overture to Coriolan

1807

Beethoven’s Overture to Coriolan is the only tragic piece in our Prometheus Festival. Indeed, in spite of the intense conflict that marks much of his music, Beethoven was something of an optimist.

Continue Reading

Egmont Overture

1810

Beethoven’s Egmont Overture is one of his many concert overtures depicting different kinds of heroic individuals.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 1

1800

In the mainstream history of Beethoven, his early works are more classical in style, hewing close to Mozart and (especially) Haydn.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 2

1802

Beethoven first realized he was becoming deaf in the summer of 1798, at age twenty-seven. After an initial episode of total deafness, Beethoven found that his hearing had become filled with an unending “maddening chorus of squealing, buzzing, and humming.”

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 3

1804

Beethoven’s Third Symphony, the Eroica, or “Heroic,” is one of the most influential pieces of music in history.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 4

1806

Beethoven’s Fourth Symphony seems an anomaly compared to the heroic Third and the fateful Fifth.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 5

1808

Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony is so familiar to us now that it might be difficult to imagine it as shocking or difficult.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 6

1808

Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony premiered on the same concert as the Fifth Symphony (December 22, 1808). The two works were quite different: Whereas the Fifth was a difficult journey from darkness to light, the Pastoral was a genial, warm-hearted journey through the countryside.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 7

1812

In the Seventh, Beethoven suffuses each movement with a unique and persistent rhythmic pattern.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 8

1812

The Eighth Symphony generally has been regarded as the slightest of Beethoven’s mature symphonies because of its short length, lighter tone, and frequent return to the musical styles and forms of the eighteenth century.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 9

1824

Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony stands as the culmination of Beethoven’s twenty-four-year career as a composer of symphonies.

Continue Reading

Grosse Fuge

1825

The Grosse Fuge (Great Fugue) is Beethoven’s most complex work. It was originally to be the last movement of his String Quartet No. 13. However, it unluckily proved to be both technically challenging for the performers and bewildering to the audience, and was, instead, turned into its own stand-alone work.

Continue Reading