A Symphonic Revolution

Beethoven: Symphony No. 3 in E-flat Major, the Eroica (1804)

By Alexander Lawler

Beethoven’s Third Symphony, the Eroica, or “Heroic,” is one of the most influential pieces of music in history. Often considered the beginning point for the romantic era of music and Beethoven’s influential “Middle Period,” this symphony cast a long shadow over European musical and philosophical life in the first half of the 19th century. The longest, largest, and loudest symphony written to that date, it also carries immense cultural baggage attached to it in the form of its title and its dedication (and subsequent retraction) to Napoleon Bonaparte. The story behind this retraction is that upon hearing from Ferdinand Ries, Beethoven’s secretary, that Napoleon had forsaken the title of First Consul for that of Emperor, Beethoven went into a rage, denounced Napoleon as “nothing but an ordinary mortal” who had only “become a greater tyrant,” and ripped the title page in half.1 Although quite likely exaggerated, the violent obliteration of Napoleon’s name on the title page of the manuscript seems to support the story’s central truth – that until that point, Beethoven held Napoleon in great esteem and had considered him an important model in the composition of the Eroica.2

For Beethoven, Napoleon was a promethean figure much like himself: a man of low status who rose through intellect and skill to become the highest power in his field and who then sought to use that power to guide the nation and elevate its people toward an enlightened future. Until he declared himself emperor, Napoleon was the guardian of the revolution and the keeper of liberty’s flame. A promethean hero can exemplify many virtues, and the one Napoleon possessed was heroism – hence, the Eroica. Although many commentators have read the symphony as overtly representing Napoleon and his exploits, at its core, the symphony and its former dedicatee share promethean heroism. Prometheus was a hero for defying the gods and granting fire to humanity; Napoleon was a hero for defying the crowned heads of Europe and protecting the fire of freedom granted to the French people by the Revolution. Similarily, Beethoven was a hero for defying musical orthodoxy in search of new ways to express complex philosophical truths and ideas through music to uplift his listeners.

To express something as vast as heroism, Beethoven began in earnest in the Eroica, in the words of Music Director Franz Welser-Möst, to “condense the message.” To that end, below is a consideration of a few moments from the symphony and how they condense and express the idea of heroism.

Beethoven encapsulated his views on heroism into just the opening eight seconds of the first movement. As you can hear in the video above, Beethoven uses two orchestral hammer blows to firmly establish the key and mood for the symphony, which the cellos, entering on the first theme seem to reinforce. However, this stability of self is quickly undercut by the descent of the cellos to a dissonant note foreign to the movement’s key of E-flat major. This sets up a conflict that spans the entire movement; this initial theme continuously seeks to establish itself securely and overcome the difficulties presented by this dissonance. Perhaps this was a statement on the nature of heroism as Beethoven saw it: that heroism was a consequence of what one does and not what one was; the theme itself is not heroic, but attains it through displays of musical heroism in the first movement as it overcomes seemingly endless obstacles on its path to finding a higher and more enlightened state.

Beethoven: Symphony No. 3, II. Marcia funebre

The Cleveland Orchestra, George Szell

Archival Recording: Severance Hall, October 17, 1946

Archival Recording: Severance Hall, May 7, 1970

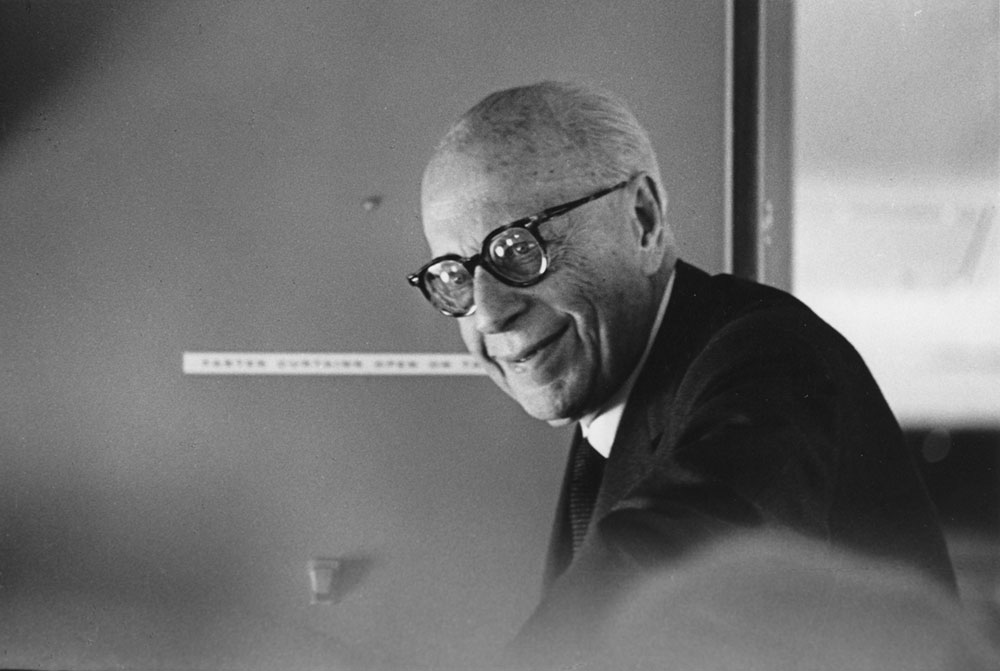

George Szell became the Orchestra’s fourth music director in 1946, only leaving the post upon his death in 1970. Like Artur Rodzinski before him, Szell raised the profile of the Orchestra in the musical world and helped the Orchestra achieve the distinction of being one of the “Big Five” American orchestras. This audio example blends two archival recordings of Szell’s and the Orchestra’s from the first and last years of his tenure as music director. The photo on the left is taken from a 1955 recording session with the Orchestra in the Masonic Auditorium, while the one on the right is Szell on a plane returning to Cleveland from the last leg of the Orchestra’s 1970 Japan tour, his last. Photograph (left) by Dan Weiner, November 1955. Photograph (right) by Peter Hastings, May 30, 1970. Both photographs courtesy of The Cleveland Orchestra Archives.

The second movement is a funeral march, which serves as a darker side to the triumph of the first movement – a connection heightened by their shared length and closely related keys. How Beethoven condenses the message here is through the frequent return to, and expansion of, the dirge-like opening theme. Through this, Beethoven takes the funeral march’s typical ternary form (two identical or similar sections with a contrasting section in the middle) and transforms it into what is essentially a rondo (a form in which a theme or section of music alternates with contrasting episodes). This focuses attention on this first theme and allows Beethoven to pair it with musical episodes of different affect in order to give the audience an opportunity to reflect upon the different ways in which the sorrow and pain of loss, the consequences of heroic struggle, can be felt: remembrance, despair, hope, and acceptance.

Beethoven: Symphony No. 3, IV. Allegro Moltoe

The Cleveland Orchestra, Christoph von Dohnányi

Archival Recording: Severance Hall, October 20, 1983.

The fourth and final movement of the symphony is an elaborate set of variations on a theme, another way which Beethoven often capitalized on forms and techniques that could turn a single short musical motif into an entire composition. The theme (which can be heard in the opening of the above audio example) is taken from Beethoven’s previous ballet, The Creatures of Prometheus, further connecting the symphony with the idea of Prometheus. The movement’s generally celebratory mood, and the contrasting presence of stormy and pensive movements, allow the movement to be heard as a series of unfolding thoughts and reflections brought on by victory.

- 1 Sir George Grove, Beethoven and His Nine Symphonies (London: Novello and Company, 1896), 54.

- 2 Nicholas Matthew, Political Beethoven (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013), 19.

- Alexander Lawler worked for the Orchestra’s Archives over three seasons while working on a Historical Musicology PhD at Case Western Reserve University. First writing the “From the Archives” online essays in the 2015/16 season, next designing a photo digitization and metadata project in the 2016/17 season and finally, in the 2017/18 centennial season with the Prometheus Project.

Essay & Audio Library

Beethoven: The Prometheus Connection

In 1812, Ludwig van Beethoven received a letter from a young pianist named Emilie M. Her letter, enclosed with a home-made embroidered pocketbook, expressed her fondness for, and appreciation of, his music.

Continue Reading

Overture to The Creatures of Prometheus

1801

Perhaps the most overt example of Beethoven’s interaction with the idea of Prometheus was his only published ballet, The Creatures of Prometheus.

Continue Reading

Leonora Overture No. 3

1806

Fidelio (1805), Beethoven’s only opera, is a celebration of freedom. In the opera, Florestan has been imprisoned by the tyrant Don Pizarro.

Continue Reading

Overture to Coriolan

1807

Beethoven’s Overture to Coriolan is the only tragic piece in our Prometheus Festival. Indeed, in spite of the intense conflict that marks much of his music, Beethoven was something of an optimist.

Continue Reading

Egmont Overture

1810

Beethoven’s Egmont Overture is one of his many concert overtures depicting different kinds of heroic individuals.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 1

1800

In the mainstream history of Beethoven, his early works are more classical in style, hewing close to Mozart and (especially) Haydn.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 2

1802

Beethoven first realized he was becoming deaf in the summer of 1798, at age twenty-seven. After an initial episode of total deafness, Beethoven found that his hearing had become filled with an unending “maddening chorus of squealing, buzzing, and humming.”

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 3

1804

Beethoven’s Third Symphony, the Eroica, or “Heroic,” is one of the most influential pieces of music in history.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 4

1806

Beethoven’s Fourth Symphony seems an anomaly compared to the heroic Third and the fateful Fifth.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 5

1808

Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony is so familiar to us now that it might be difficult to imagine it as shocking or difficult.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 6

1808

Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony premiered on the same concert as the Fifth Symphony (December 22, 1808). The two works were quite different: Whereas the Fifth was a difficult journey from darkness to light, the Pastoral was a genial, warm-hearted journey through the countryside.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 7

1812

In the Seventh, Beethoven suffuses each movement with a unique and persistent rhythmic pattern.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 8

1812

The Eighth Symphony generally has been regarded as the slightest of Beethoven’s mature symphonies because of its short length, lighter tone, and frequent return to the musical styles and forms of the eighteenth century.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 9

1824

Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony stands as the culmination of Beethoven’s twenty-four-year career as a composer of symphonies.

Continue Reading

Grosse Fuge

1825

The Grosse Fuge (Great Fugue) is Beethoven’s most complex work. It was originally to be the last movement of his String Quartet No. 13. However, it unluckily proved to be both technically challenging for the performers and bewildering to the audience, and was, instead, turned into its own stand-alone work.

Continue Reading