What Utopia Feels Like:

Beethoven's Symphony No. 6, "The Pastoral" (1808)

By Alexander Lawler

Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony premiered on the same concert as the Fifth Symphony (December 22, 1808). The two works were quite different: Whereas the Fifth was a difficult journey from darkness to light, the Pastoral was a genial, warm-hearted journey through the countryside. The Pastoral symphony is the most programmatic of Beethoven’s symphonies: Each of its five movements bears a title loosely depicting the experiences of an anonymous figure moving through the countryside. However, the Pastoral is one of Beethoven’s most forward-looking compositions, as Music Director Franz Welser-Möst describes in the video below.

Music Director Franz Welser-Möst discusses another side to Beethoven’s style — pastoral and distinctly non-heroic — and connects it to Romantic-era ideas of sensation and feeling.

There seems to be a conscious effort by Beethoven to prioritize sensation and emotion over form and literal depictions of nature in the Pastoral. According to Beethoven scholar Lewis Lockwood, Beethoven sought to find the best of both worlds in his Pastoral: to illustrate these naturalistic scenes through music that would paint them in tones, but, above all, to have the music be, in Beethoven’s words, “‘understood without a description, as it is more feeling than tone-painting.’”1 Essentially, by drawing on musical tropes of nature to cue a listener into the general ambiance, Beethoven could focus his compositional efforts on the expression of emotion. This is what makes the symphony truly Romantic. Composer Robert Schumann felt as much, writing that Beethoven’s remarks about the symphony provided “ ‘an entire aesthetic system for [future] composers.’”2

Whereas works like the Eroica or Egmont celebrate heroic individuals and their struggles, the Pastoral ultimately seems to celebrate the strength of community and harmony – whether it be of nature or people. Franz compares the last movement of the Pastoral to the first of the Eroica: Both of their main themes are derived from the notes of one chord, which he describes as, “the harmony itself is the theme.” However, both themes are very different, which suits Beethoven’s aims in each symphony. The opening theme of the Eroica constantly fights off dissonance, and is about heroism, conflict, and victory; in contrast, the theme of the last movement of the Pastoral celebrates consonance, signifying, as described, the harmony among different people.

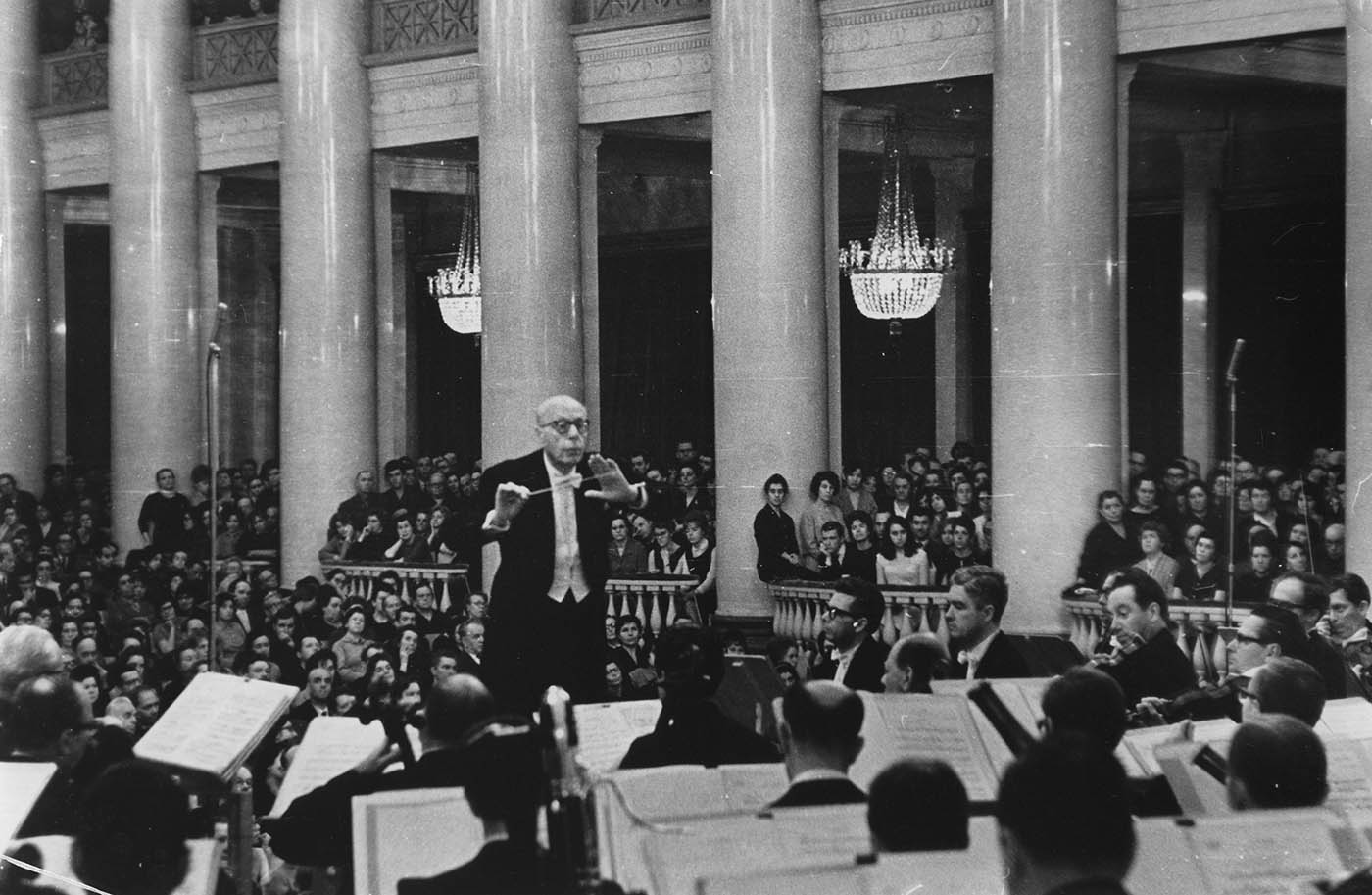

![A portrait of the Orchestra and von Dohnányi in Severance Hall from his final season as music director [2001-02]. Photograph by Roger Mastroianni](/globalassets/1819/archives/prometheus/symphony-6-4.jpg)

In line with Franz’s musical analysis and the festival’s promethean theme, musicologist Richard Will has interpreted the Pastoral (composed during the heyday of Napoleon’s empire in Europe) as an “effort to conjure a world protected from violence, degradation, human foible” in which the people escape calamity by the “apparent intervention of a higher power” and are inspired to “redeem [themselves].”3 If works such as the Eroica or the Fifth Symphony are about heroic conflict and the move from darkness to light, then this symphony is about the “utopia” that emerges from that struggle: a beautiful portrait of a “pastoral arcadia.”4

- 1 Lewis Lockwood, Beethoven: The Music and the Life (New York: W.W. Norton, 2005), 225.

- 2 David Wyn Jones, Pastoral Symphony (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 82.

- 3 Richard Will, The Characteristic Symphony in the Age of Haydn and Beethoven (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 156-157.

- 4 Maynard Solomon, Beethoven, second revised edition (New York: Schirmer Books, 1998), 404

- Alexander Lawler worked for the Orchestra’s Archives over three seasons while working on a Historical Musicology PhD at Case Western Reserve University. First writing the “From the Archives” online essays in the 2015/16 season, next designing a photo digitization and metadata project in the 2016/17 season, and finally, in the 2017/18 centennial season with the Prometheus Project.

Essay & Audio Library

Beethoven: The Prometheus Connection

In 1812, Ludwig van Beethoven received a letter from a young pianist named Emilie M. Her letter, enclosed with a home-made embroidered pocketbook, expressed her fondness for, and appreciation of, his music.

Continue Reading

Overture to The Creatures of Prometheus

1801

Perhaps the most overt example of Beethoven’s interaction with the idea of Prometheus was his only published ballet, The Creatures of Prometheus.

Continue Reading

Leonora Overture No. 3

1806

Fidelio (1805), Beethoven’s only opera, is a celebration of freedom. In the opera, Florestan has been imprisoned by the tyrant Don Pizarro.

Continue Reading

Overture to Coriolan

1807

Beethoven’s Overture to Coriolan is the only tragic piece in our Prometheus Festival. Indeed, in spite of the intense conflict that marks much of his music, Beethoven was something of an optimist.

Continue Reading

Egmont Overture

1810

Beethoven’s Egmont Overture is one of his many concert overtures depicting different kinds of heroic individuals.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 1

1800

In the mainstream history of Beethoven, his early works are more classical in style, hewing close to Mozart and (especially) Haydn.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 2

1802

Beethoven first realized he was becoming deaf in the summer of 1798, at age twenty-seven. After an initial episode of total deafness, Beethoven found that his hearing had become filled with an unending “maddening chorus of squealing, buzzing, and humming.”

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 3

1804

Beethoven’s Third Symphony, the Eroica, or “Heroic,” is one of the most influential pieces of music in history.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 4

1806

Beethoven’s Fourth Symphony seems an anomaly compared to the heroic Third and the fateful Fifth.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 5

1808

Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony is so familiar to us now that it might be difficult to imagine it as shocking or difficult.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 6

1808

Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony premiered on the same concert as the Fifth Symphony (December 22, 1808). The two works were quite different: Whereas the Fifth was a difficult journey from darkness to light, the Pastoral was a genial, warm-hearted journey through the countryside.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 7

1812

In the Seventh, Beethoven suffuses each movement with a unique and persistent rhythmic pattern.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 8

1812

The Eighth Symphony generally has been regarded as the slightest of Beethoven’s mature symphonies because of its short length, lighter tone, and frequent return to the musical styles and forms of the eighteenth century.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 9

1824

Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony stands as the culmination of Beethoven’s twenty-four-year career as a composer of symphonies.

Continue Reading

Grosse Fuge

1825

The Grosse Fuge (Great Fugue) is Beethoven’s most complex work. It was originally to be the last movement of his String Quartet No. 13. However, it unluckily proved to be both technically challenging for the performers and bewildering to the audience, and was, instead, turned into its own stand-alone work.

Continue Reading