"Als ob" or Making Old New Again:

Beethoven's Symphony No. 8 in F Major (1812)

By Alexander Lawler

The Eighth Symphony generally has been regarded as the slightest of Beethoven’s mature symphonies because of its short length, lighter tone, and frequent return to the musical styles and forms of the eighteenth century. However, beneath the gaiety of its surface lies much complexity and a promethean connection. Listen below to Music Director Franz Welser-Möst describe how he came to appreciate the symphony in a new light when he viewed it through the lens of “als ob” (as if):

Music Director, Franz Welser-Möst Franz discusses how the Eighth Symphony is a reinvention of the symphonic past.

The idea of “als ob” (as if) is a sophisticated way of returning to the past: doing something “as if” it were something else. Instead of simply copying or repeating older musical styles or forms, Beethoven reinvents them by infusing musical elements of his time. Beethoven scholar Lewis Lockwood describes this “reanimation of the classical manner” as “an expression of [Beethoven’s] sense of freedom.”1 If in the Seventh Symphony, Beethoven explored rhythm as an expanded dimension of music, then in the Eighth, Beethoven is reminding us that there is much that the musical past can tell us and that one does not need to be a pioneer and revolutionary to have something to say.

You can hear some of this in the third movement. Beethoven returns to the minuet and trio, a distinctly eighteenth-century dance form and, prior to his popularization of the scherzo, the typical third movement of a classical symphony. However, Beethoven’s minuet freely mixes new and old: The middle trio section is scored in imitation of its roots (a literal trio of musicians), but, as Franz remarks, when Beethoven brings in the strings, the sound changes to something much more romantic. In the minuet sections of the movement, Beethoven playfully comments on the minuet’s grand and sometimes pompous associations with past nobility through exaggerated accents and dynamic shifts.

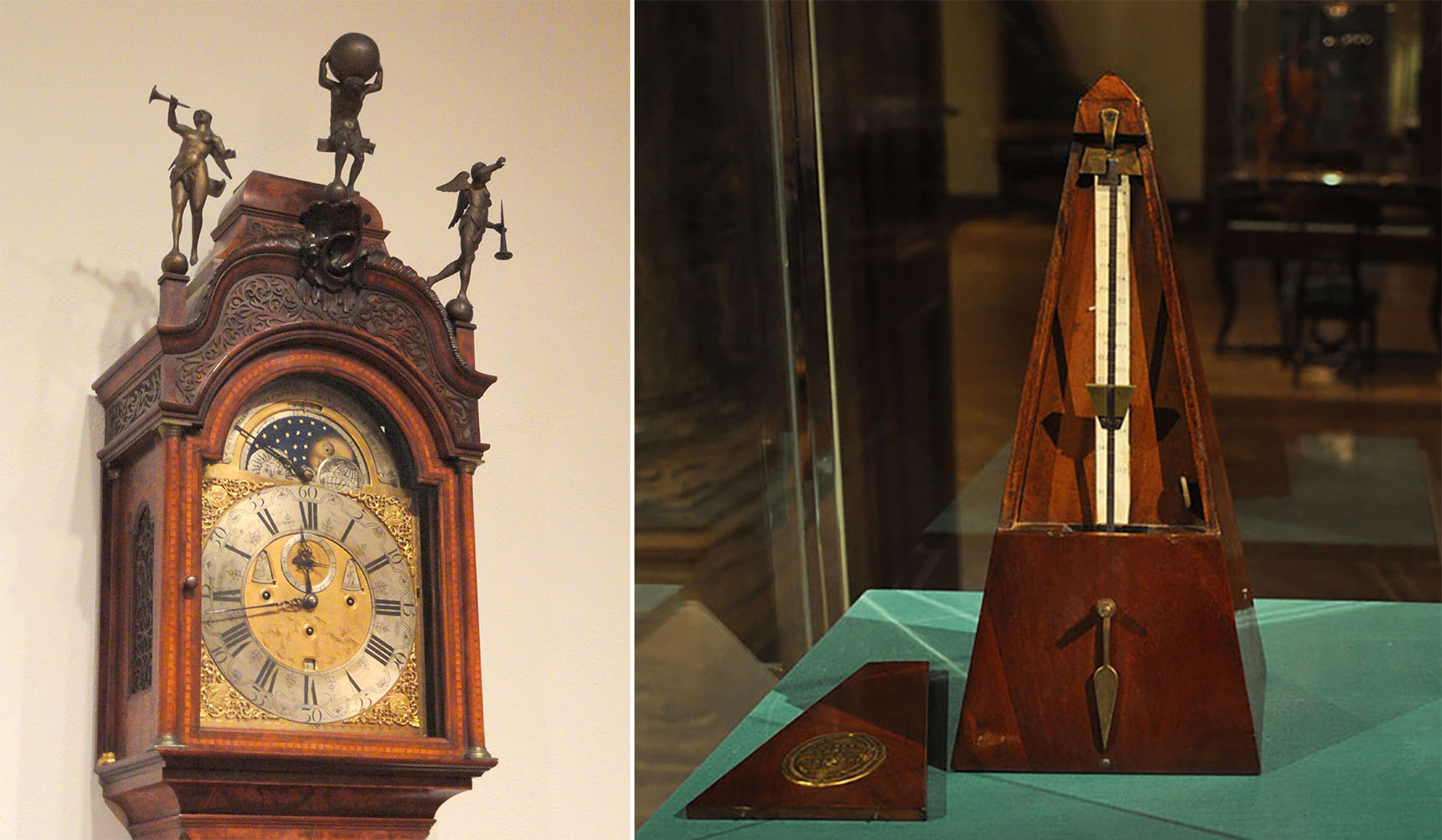

A Musical Clock: Symphony No. 8, II: Allegretto Scherzando

The superficially simple second movement is an excellent example of this engagement with the past. Dominated by a musical imitation of a ticking clock, this movement is commonly considered to be a representation of the beating of a metronome, a new device for which Beethoven should great enthusiasm.2 However, this interpretation is now considered apocryphal.3 In line with the idea of “als ob,” the movement can be heard (and likely was heard at the time) as an imitation of a major classical work by Beethoven’s teacher, Haydn, Symphony No. 101 in D Major, “The Clock.” Additionally, this movement harkens back to an older meaning of Scherzo as a “joke” – with this movement then being “a little joke.”4 Listen below to the opening of this movement, taken from a 1936 recording of The Cleveland Orchestra, Artur Rodzinski conducting:

However, according to musicologists Martin Geck and Lewis Lockwood, it is not simply a return to an older classical model, but a sophisticated, sly play on the idea of a musical clock. Lockwood and Geck both note how the movement playfully deconstructs the idea both of a clock and also of a musical imitation of a clock: unlike a clock’s precise, regular mechanisms, those of this movement are out of whack: timings get off progressively, phrases get stuck in ruts, and there are unexpected surprising shifts in tone.5Listen to the remainder of the movement below in a 2011 recording with Franz conducting:

To a promethean figure in art, creating something that can inspire and uplift others does not require the work be on an epic scale, of vast dimensions, or completely new and revolutionary. There is value in the small and the already-done, and Beethoven’s Eighth Symphony stands as a reminder of this truth.

- 1 Lewis Lockwood, Beethoven’s Symphonies: An Artistic Vision (New York: W.W. Norton, 2015): 171.

- 2 The story behind this attribution is that at an 1812 farewell dinner in Vienna for Beethoven (before he left for Linz to visit his brother and work on his Eighth Symphony), Beethoven composed a canon in honor of Maelzel and his device, the chronometer (later renamed the metronome). The tune of this canon later became the source of the main theme for the symphony’s second movement. Source: Anton Felix Schindler, Beethoven as I Knew Him, translated by Constance S. Jolly, edited by Donald W. MacArdle (Meneola, NY: Dover, 1996), 170-171.

- 3 Martin Geck, Beethoven, translated by Anthea Bell (London: Haus Publishing, 2003), 87.

- 4 Lockwood, Beethoven’s Symphonies, 180-181.

- 5 Geck, Beethoven’s Symphonies: Nine Approaches to Art and Ideas, translated by Stewart Spencer (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2017), 129-130; Lockwood, Beethoven’s Symphonies, 180-182.

- Alexander Lawler worked for the Orchestra’s Archives over three seasons while working on a Historical Musicology PhD at Case Western Reserve University. First writing the “From the Archives” online essays in the 2015/16 season, next designing a photo digitization and metadata project in the 2016/17 season and finally, in the 2017/18 centennial season with the Prometheus Project.

Essay & Audio Library

Beethoven: The Prometheus Connection

In 1812, Ludwig van Beethoven received a letter from a young pianist named Emilie M. Her letter, enclosed with a home-made embroidered pocketbook, expressed her fondness for, and appreciation of, his music.

Continue Reading

Overture to The Creatures of Prometheus

1801

Perhaps the most overt example of Beethoven’s interaction with the idea of Prometheus was his only published ballet, The Creatures of Prometheus.

Continue Reading

Leonora Overture No. 3

1806

Fidelio (1805), Beethoven’s only opera, is a celebration of freedom. In the opera, Florestan has been imprisoned by the tyrant Don Pizarro.

Continue Reading

Overture to Coriolan

1807

Beethoven’s Overture to Coriolan is the only tragic piece in our Prometheus Festival. Indeed, in spite of the intense conflict that marks much of his music, Beethoven was something of an optimist.

Continue Reading

Egmont Overture

1810

Beethoven’s Egmont Overture is one of his many concert overtures depicting different kinds of heroic individuals.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 1

1800

In the mainstream history of Beethoven, his early works are more classical in style, hewing close to Mozart and (especially) Haydn.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 2

1802

Beethoven first realized he was becoming deaf in the summer of 1798, at age twenty-seven. After an initial episode of total deafness, Beethoven found that his hearing had become filled with an unending “maddening chorus of squealing, buzzing, and humming.”

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 3

1804

Beethoven’s Third Symphony, the Eroica, or “Heroic,” is one of the most influential pieces of music in history.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 4

1806

Beethoven’s Fourth Symphony seems an anomaly compared to the heroic Third and the fateful Fifth.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 5

1808

Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony is so familiar to us now that it might be difficult to imagine it as shocking or difficult.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 6

1808

Beethoven’s Pastoral Symphony premiered on the same concert as the Fifth Symphony (December 22, 1808). The two works were quite different: Whereas the Fifth was a difficult journey from darkness to light, the Pastoral was a genial, warm-hearted journey through the countryside.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 7

1812

In the Seventh, Beethoven suffuses each movement with a unique and persistent rhythmic pattern.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 8

1812

The Eighth Symphony generally has been regarded as the slightest of Beethoven’s mature symphonies because of its short length, lighter tone, and frequent return to the musical styles and forms of the eighteenth century.

Continue Reading

Symphony No. 9

1824

Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony stands as the culmination of Beethoven’s twenty-four-year career as a composer of symphonies.

Continue Reading

Grosse Fuge

1825

The Grosse Fuge (Great Fugue) is Beethoven’s most complex work. It was originally to be the last movement of his String Quartet No. 13. However, it unluckily proved to be both technically challenging for the performers and bewildering to the audience, and was, instead, turned into its own stand-alone work.

Continue Reading