Even Beethoven Was Once New

Commissions and Premieres with The Cleveland Orchestra

By Alex Lawler (November 2015)

It’s hard to imagine it, but there was a time when Beethoven’s nine symphonies were not performed regularly, or even at all. In order to come to life musically, they had to be premiered by an orchestra, and very often commissioned by a patron or a publisher in order for Beethoven to support himself during their composition. The Cleveland Orchestra has been active in both commissioning and premiering new works throughout its near century existence. There are many reasons why the Orchestra does this: Supporting new music, honoring members of the Orchestra, promoting something specifically new and unheard of, or bringing something already performed elsewhere in the world to attention here. To talk about all of the pieces the Orchestra has premiered or commissioned would take a small book, so let’s look at three examples:

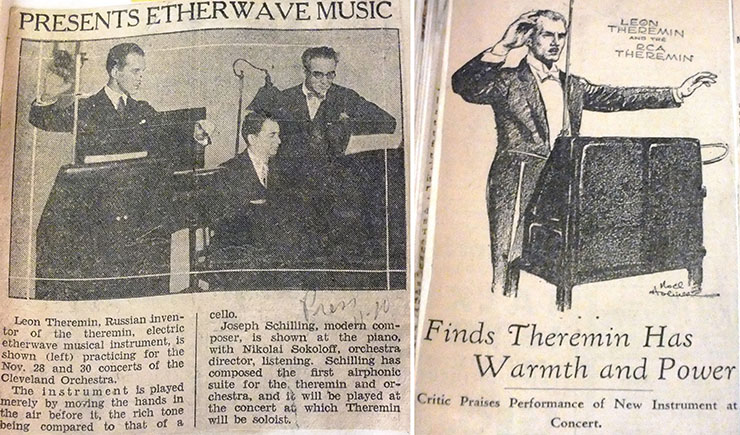

Promoting a New Instrument – Joseph Schillinger’s First Airphonic Suite for RCA Theremin and Orchestra (composed and premiered 1929)

The Theremin was invented by Russian scientist Léon Theremin, after whom the instrument was named. Using proximity sensors, the instrument could create different pitches based on the distance of the right hand from a vertical antenna, and different volumes upon the distance of the left hand from a horizontal circular antenna. First demonstrated in the early 1920s in the Soviet Union, Theremin brought it to the United States in 1927. RCA (The Radio Corporation of America) became interested soon after, and in 1929 began to manufacture the Theremin (now named the RCA Theremin).

The Cleveland Orchestra’s connection to the Theremin dates from 1929, when Joseph Schillinger, a composer and teacher who was a recent émigré from the Soviet Union, approached Nikolai Sokoloff (the Orchestra’s music director) with a proposal for a piece featuring the RCA Theremin to capitalize on the new instrument’s notoriety. Sokoloff, having already been impressed by the Theremin at a previous demonstration and (according to historian Albert Glinsky) wanting to scoop Stokowski and The Philadelphia Orchestra, agreed. Joseph Schillinger’s First Airphonic Suite for RCA Theremin and Orchestra (1929) was composed in a romantic style to showcase both the uniqueness of the Theremin while grounding it within the familiar. This was important, as many in the 1920s felt the idea of creating musical sound from electricity was strange and unsettling. This can be seen in Sokoloff’s description of the first rehearsal the Orchestra had with the Theremin:

We started the rehearsal…suddenly the thing emitted the most unearthly, ear-splitting shriek and, to my horror, I saw our wonderful first horn, Isadore Berv, keel over in a dead faint. It took some time to revive the poor fellow and his instrument was battered by his fall. Theremin was abject in his apologies – his hand had gotten into the wrong position and I was assured that it would never happen again. I wasn’t too sure that it wouldn’t, but we finished the rehearsal without any more casualties. (Albert Glinsky, Theremin: Ether Music and Espionage, 107.)

Right: Plain Dealer, November 29, 1929: A characteristic review of the concert, focusing on Theremin’s coaxing of sound of great “power” and “warmth”

Not everyone reacted this way to the Theremin, thankfully! The Cleveland Press described its sound as “the rich tone…of a cello,” and reviews of the Theremin’s premiere in Cleveland were all fairly positive. These reviews may have been assisted by Léon Theremin himself performing his instrument for the premiere. Unfortunately, while no archival recording of Schillinger’s First Airphonic Suite exists, you can listen here.

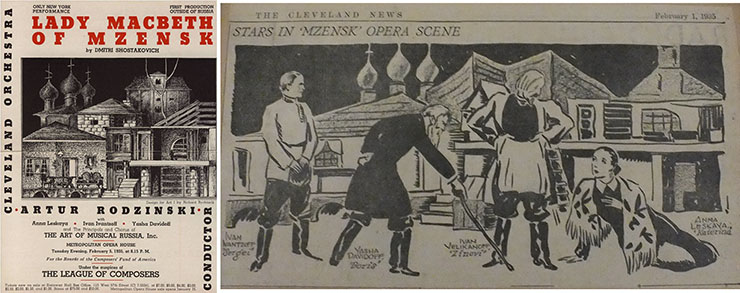

Bringing the World’s Best to Cleveland: Dmitri Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth of the Mzensk District (composed 1932; premiere in Soviet Union 1934; premiere outside of the Soviet Union 1935)

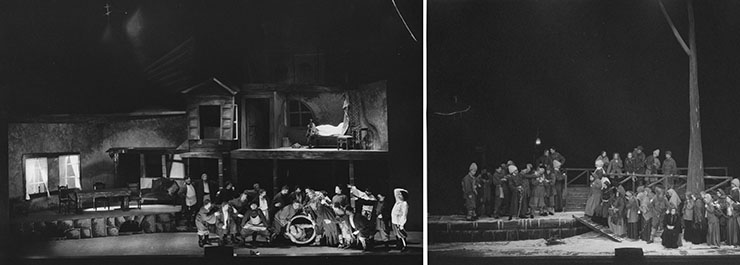

Perhaps one of the most famous premieres at The Cleveland Orchestra was not an orchestral piece, but an opera. Artur Rodziński, the second Music Director of The Cleveland Orchestra, had a particular passion for opera; beginning in 1933 he began a series of staged opera performances at Severance Hall, beginning with Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde. During a conducting trip to the Soviet Union in 1934, Rodziński was present at the premiere of Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth of the Mzensk District, which bowled him over with its unrelenting realism and intensity, leading him to attend the opera six more times. After a difficult fight to secure the performing rights from the Soviet government, Rodziński got the go-ahead to do the premiere of the opera outside of the Soviet Union.

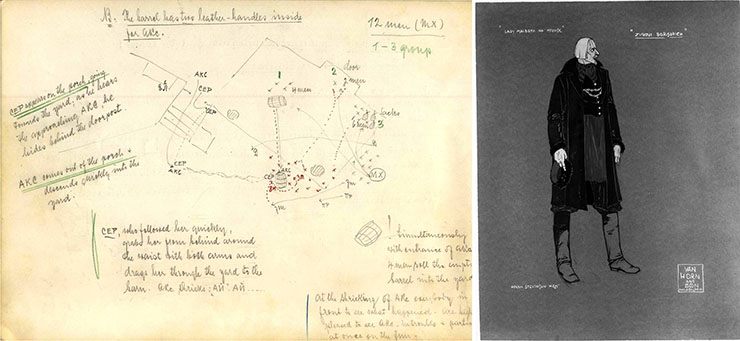

Top Right: Character sketch done by the costume designer, Helen Stevenson West, of Zinovi (Zinovy) Borisovich, the husband of Katerina

Dmitri Shostakovich’s opera, Lady Macbeth of Mzensk, had been a smash success in the Soviet Union upon its premiere in 1933. The opera tells the tragic story of Katerina, the neglected wife of the merchant Zinovy, whose father regularly torments her. Seeking escape from her boring, emotionally unfulfilling life, she enters into an affair with Sergei, one of Zinovy’s workers. After much conflict, in which Katerina poisons her father-in-law and strangles her husband (with the assistance of Sergei), they are eventually discovered and exiled to Siberia. It is there that Katerina is again betrayed by the men in her life, and Sergei abandons her for a younger woman, Sonyetka, leading to Katerina drowning herself and Sonyetka in an icy river. The opera’s frank depiction of sexuality, violence, and its feminist themes contributed to both the opera’s initial popularity, and later censoring by Stalin in 1936, after which the opera disappeared from performance for about four decades.

Right: Photograph of the Siberian Exile scene (Act 4, scene 9)

The production was the source of much excitement and enthusiasm in Cleveland, with newspapers reporting about the premiere many months in advance. The weeks leading up to the run, and the run itself were covered extensively, with many nearly half page articles with pictures and glowing descriptions. While a sophisticated piece of musical realism, much of the commentary focused on the work’s Soviet origins or its connection to some sort of mythic “Russianness.” While a tremendous success both in Cleveland and in New York City, where the opera was taken on tour in February 1935, Stalin’s censoring of the opera in 1936 put a premature close to future productions of the opera until the 1970s. The revival of the original 1933 version of the opera was only possible in more recent times because of Rodziński’s preservation of many original and priceless scores, documents and sketches.

Right: Review of Lady Macbeth of Mzensk in the Cleveland Plain Dealer, Early February 1935 (will find specific date when retaking photography)

Supporting New Music: Kaija Saariaho’s Orion (composed 2002; premiered 2003)

Another reason that The Cleveland Orchestra commissions and premieres so many new works is that it is the best way for Classical music to continue to grow, and to give new audiences new music to listen to that they might feel speaks to them in a different way than say Beethoven or Brahms.

The music of Finnish composer Kaija Saariaho (1952 - ) has been performed frequently by The Cleveland Orchestra over the past decade. Saariaho is one of the leading classical composers of today. Born in 1952 in Helsinki, Finland, she is a graduate of the Sibelius Academy. In 1982, she began to study at IRCAM (Institute for Research and Coordination in Acoustics/Music) in Paris, where she developed a mastery of the use of computers and mathematics in music. Saariaho combines this technical wizardry with an intent to, in the words of her own official biography, make her music an “urgent communication from composer to listener of ideas, images and emotions.” (http://saariaho.org/biography/).

The first work of Saariaho’s that The Cleveland Orchestra performed was a commission – Orion. The piece, inspired by Orion as the celestial constellation and mythological symbol is in three movements, all reflecting a different aspect: “Memento Mori” (translation: remember you must die; A reflection on mortality), “Winter Sky” (the time when Orion is most visible), and “Hunter” (reflecting the symbolism of the constellation in Greek mythology). More could be said about this stellar work, but I will leave the rest to her music and own words, as can be heard below:

Alex Lawler was an intern the 2015-16 season with The Cleveland Orchestra Archives. He is a PhD student in musicology at Case Western Reserve University.

All photographs and recordings courtesy of The Cleveland Orchestra Archives (Exception being the signed portrait of Kaija Saariaho, credit to Musikverein’s October 2003 Program Book)

Want to find out more?

- The Cleveland Orchestra Story: “Second to None” by Donald Rosenberg – Read about the history of The Cleveland Orchestra, with an appendix that lists many of the Orchestra’s premieres

- Excellent article by past Archives Intern Kate Rodgers (CWRU musicology PhD candidate) which features a discussion of the Orchestra’s history with Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth of Mzensk