From Score to Sound

Recording Rachmaninoff’s Symphony in 1928

By Kate Rogers (March 2015)

Recording technologies have come a long way since The Cleveland Orchestra cut its first commercial record in 1924. In those early days of recording, pieces often had to be modified to fit on 78 rpm discs, often leading conductors to condense musical works so that they could be commercially viable. Sometimes composers would listen to the concerns of orchestra conductors, revising their scores to be more acceptable for both live performance and commercial recording. One of those composers was Sergei Rachmaninoff, longtime friend of The Cleveland Orchestra’s first conductor, Nikolai Sokoloff.

From 1923 to 1942 Rachmaninoff visited Cleveland at the invitation of the Orchestra to perform his three piano concerti and his Rhapsody on a Theme by Paganini. Cleveland was also one of the first cities in the United States to witness performances of Rachmaninoff’s symphonies, and The Cleveland Orchestra was the first ensemble ever to record his stunning Symphony No. 2 in E minor. As The Cleveland Orchestra’s next performance of this symphony approaches, let’s examine Rachmaninoff’s own changes to his score of the work, and the history behind the piece’s first recording.

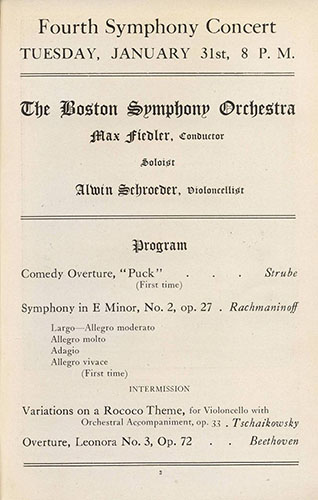

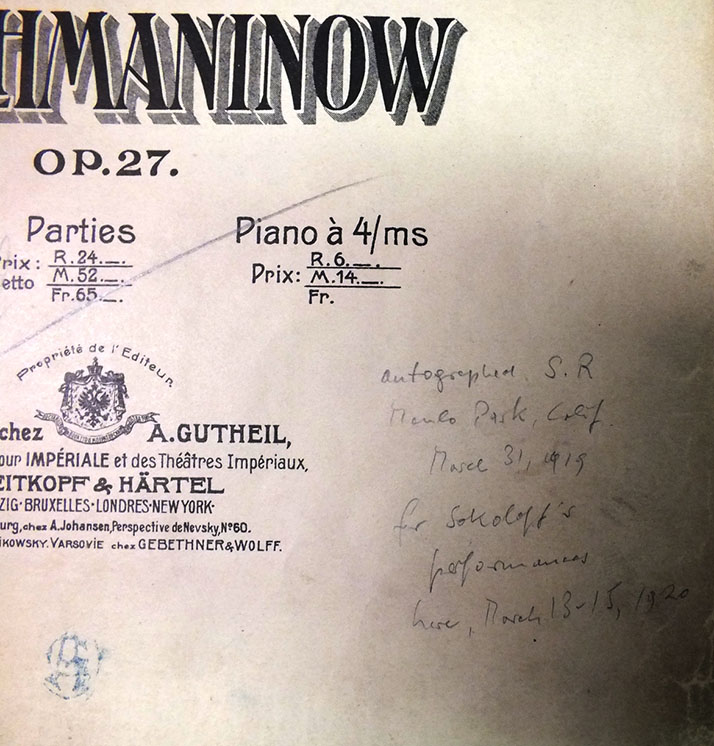

Rachmaninoff’s Symphony No. 2 was first performed in Cleveland by the Boston Symphony Orchestra in 1911, just three years after its world-premiere in St. Petersburg. During the summer of 1919, Sokoloff approached Rachmaninoff about making a revised edition of the piece for The Cleveland Orchestra to perform, as he felt the current version was too long for practical concert purposes. Rachmaninoff admitted that the score could stand to be shortened, and the two musicians prepared a new score to use for the upcoming performance of the work. In order to create a tighter (and more performable) version of the symphony, the composer altered tempi, made changes to the orchestration, and made cuts to all movements of the piece. The Cleveland Orchestra played the symphony for the first time as part of their second season in March of 1920, Sokoloff conducting from the score that reflected Rachmaninoff’s changes.

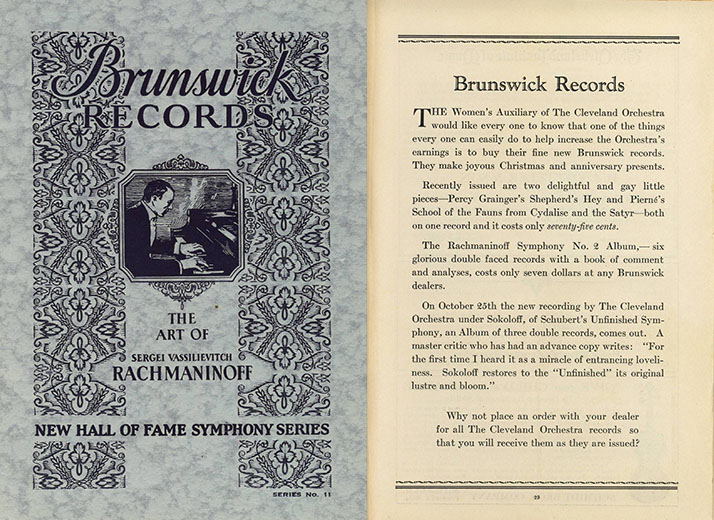

Rachmaninoff’s Symphony No. 2 quickly became a big hit: over the next eight years, Sokoloff and The Cleveland Orchestra performed it thirty-three times at home and on tour, using the score that had been prepared by the composer. Sokoloff led the ensemble in their first commercial recording of the piece in May of 1928. Only four years earlier, in 1924, The Cleveland Orchestra had made its debut commercial recording, a condensed version of Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture which fit onto one 78 rpm disc. Rachmaninoff’s lengthy symphony was another story: the recording took up both sides of six discs, despite Rachmaninoff’s edits to the score! Click hereto hear an excerpt of this early recording, taken from the second movement of the piece.

Setting this symphony to vinyl was no easy task. This landmark recording represents not only the Orchestra’s first major commercial release, but also the world-premiere recording of the symphony. In his unpublished memoirs, Sokoloff describes the recording experience and some of Rachmaninoff’s revisions to the score:

In spite of our calamitous start, we continued recording and, in 1928, even recorded for Brunswick the first “album” of a symphony ever attempted. This was Rachmaninoff’s Symphony No. 2, which took six twelve-inch records (that is twelve sides – twelve perfect wax bases!) to record. Fortunately, this was done in the Brunswick studios in New York and there were no make-shift seating arrangements to collapse under any musician [as had happened during an earlier recording session!].

Also fortunately, I had seen Rachmaninoff the summer before and, when I told him we were going to record his Second Symphony, he immediately said that he would like to make some cuts in it about which he had been thinking seriously for some time as the symphony was far too long. Also, that he wanted to make a change in the orchestration at the end of the slow movement and give me the exact tempo he wished in the Scherzo, which had been given an incorrect metronome mark when the score was published.

Rachmaninoff’s revisions and cuts are all recorded in my score, which I left with the Cleveland Orchestra. I feel sure the present librarian would be gracious enough to allow any conductor, wishing to know Rachmaninoff’s own final revisions, to look at it. Even with the cuts, it took us four hours of almost every morning of a week in New York to record it!

—from Eleanor Reynolds Sokoloff’s unpublished typescript of her husband’s memoirs, recorded in early 1965. Courtesy of Cleveland Orchestra Archives.

Thankfully, all of the hard work paid off – the recording was a huge success and received large amounts of press coverage. The September 1928 issue of Phonograph Monthly Review praised the recording as “a phonographic jewel of the very first water,” also suggesting that “it contributes a note to recorded music that has not been known before.” The recording sold for seven dollars (a little over $95 today!), and was prominently advertised in The Cleveland Orchestra’s 1928-29 season program books.

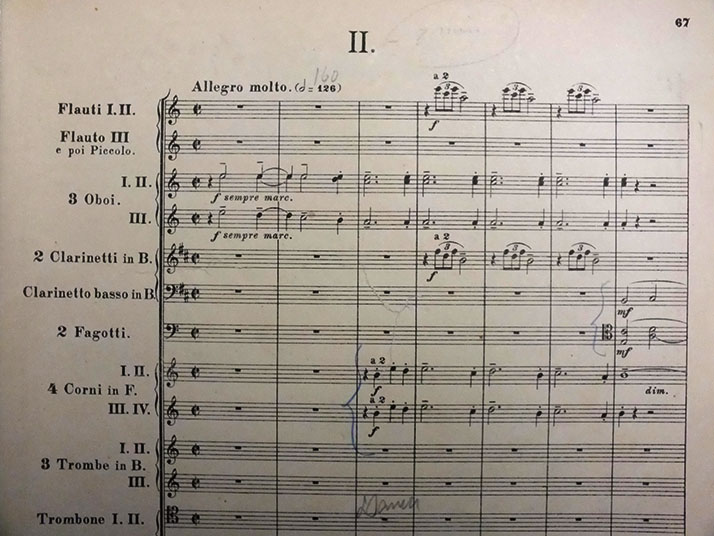

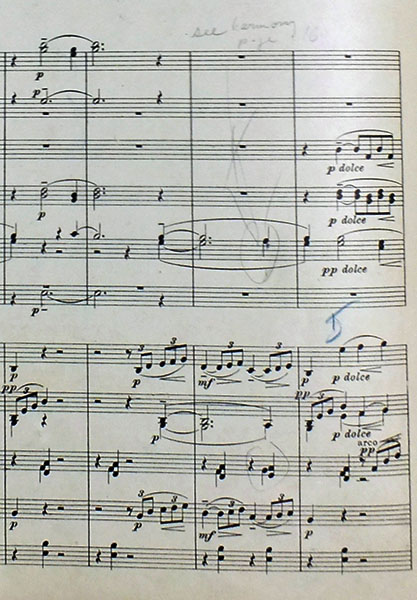

Sokoloff’s score of Rachmaninoff’s Symphony No. 2 is held in The Cleveland Orchestra’s Music Library. In addition to alterations of tempo and orchestration, Rachmaninoff made cuts to all of the movements, and even removed an entire section of twelve pages from the fourth movement!

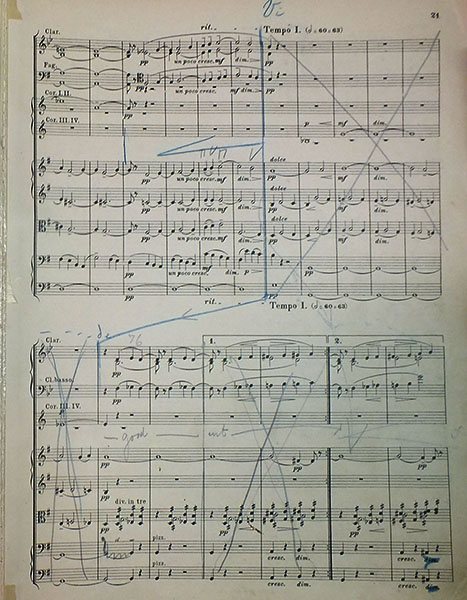

Both Sokoloff and Artur Rodzinski, Sokoloff’s successor as conductor of The Cleveland Orchestra, took this cut (see below) in the first movement. Sokoloff has marked the cut in blue pencil, starting with the syllable “vi” at Tempo I and ending with “de” in the second bar of the second staff. The gray pencil markings crossing out these measures, as well as an indication to cut the first ending, may have been written in later.

Many of Rachmaninoff’s and Sokoloff’s original changes are still visible on the score, though others have been erased. Artur Rodzinski and other Cleveland Orchestra conductors used the same score for their own performances after Sokoloff and wrote in their own sets of cuts. At least four different hands are present in the score, ranging from heavy lines in blue pencil to light gray pencil markings. Since no set of cuts is considered “standard,” the score now holds layers upon layers of possible performance variations.

Rachmaninoff’s changes to the score of his symphony and The Cleveland Orchestra’s 1928 recording of the piece both show that a score by itself is not a fixed piece of art. Instead, composers, performers, and conductors come together to create something new for their audiences every time they take the stage or create a commercial recording.

Kate Rogers is an intern this season with The Cleveland Orchestra Archives.

She is a PhD student in musicology at Case Western Reserve University.

Looking for more?

Click here to read about other cuts to the Symphony: Clinton F. Nieweg discusses cuts in the piece in detail with Ron Whitaker, retired Principal Librarian of The Cleveland Orchestra.

Photographs, audio clips, and excerpt from Sokoloff’s memoirs courtesy of The Cleveland Orchestra Archives.