From Ballparks to Concert Halls

Innovations in Opera with The Cleveland Orchestra

Cleveland is known for producing new and exciting developments in the arts, and the genre of opera is no exception. Ever since the founding of the Musical Arts Association in 1915, opera has held a strong presence in Cleveland. In the last 100 plus years, The Cleveland Orchestra has performed over 75 operas either in concert, semi-staged, or fully-staged productions. The Orchestra’s innovations in venue, staging, and choice of operatic subject material continue to shape the future of opera in Northeast Ohio.

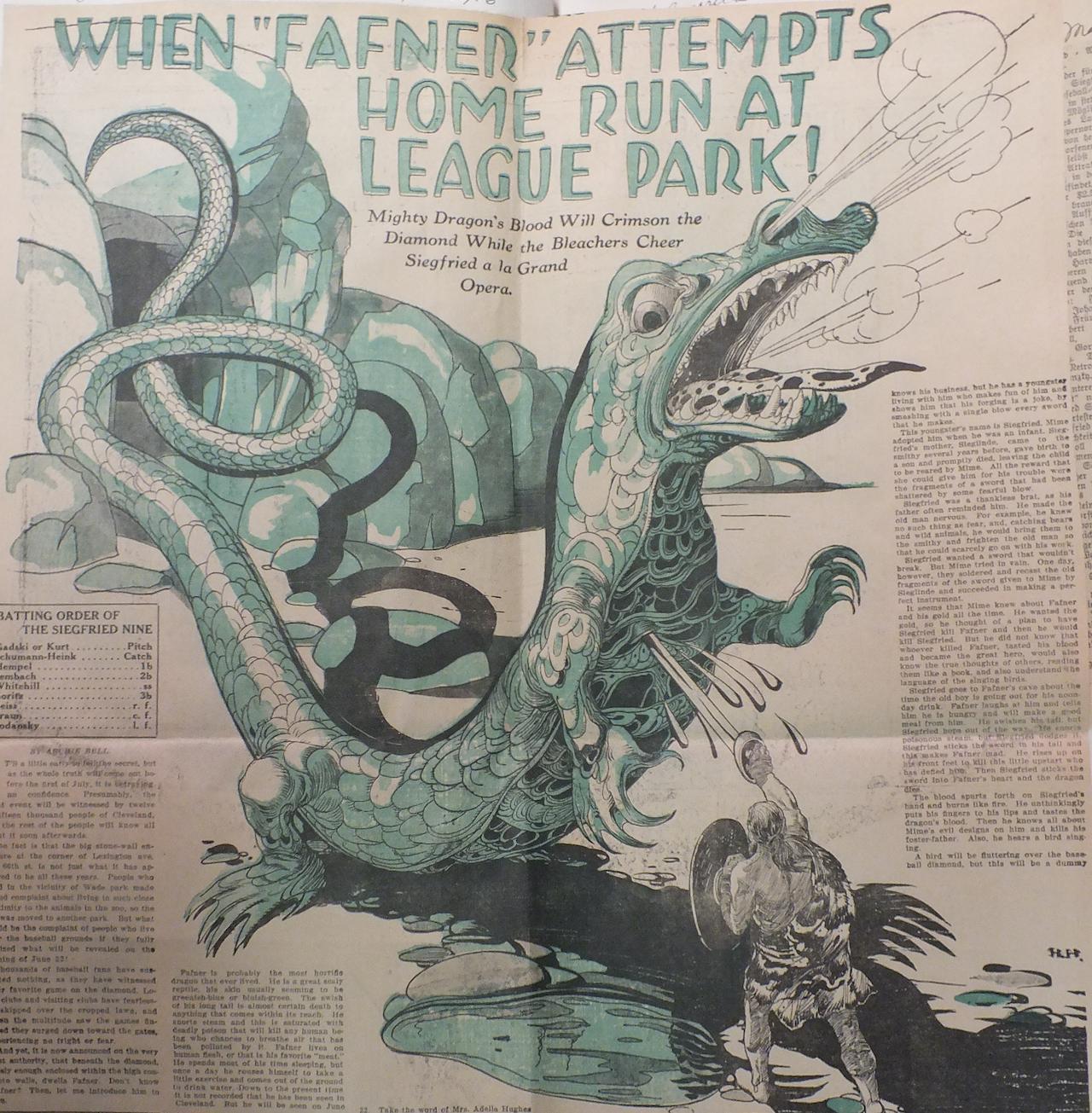

The history of opera performances in Cleveland sponsored by the Musical Arts Association dates back to 1915, three years before the founding of The Cleveland Orchestra. During this time, opera was performed in Cleveland by visiting opera companies, such as the New York Metropolitan Opera and Boston-National Grand Opera Company. Perhaps the most memorable of these performances was an open-air presentation of Wagner’s Siegfried in 1916. Masonic Hall and Grey’s Armory, the typical places for performing arts events in Cleveland at the time, were not large enough to accommodate the audiences or sets needed for the production, so there was only one option: opera at the ballpark!

Adella Prentiss Hughes, arts impresario and later founder of The Cleveland Orchestra, rented Cleveland’s League Park stadium for a performance of the opera. The performance featured a specially-constructed permanent portable stage, and the entire production cost $20,000 to put on for a single night – nearly $350,000 in today’s dollars! Conductor Arthur Bodansky led the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra that night, and among the cast were the European superstars – Johannes Sembach in the role of Siegfried, along with Melanie Kurt in the role of Brunnhilde, and Ernestine Schumann-Heink as Erda. This opera was “fully-staged,” meaning that scenery, costumes, and choreography accompanied the music. With such a unique combination of performing forces and venue, it is no surprise that over 10,000 audience members showed up for the spectacle.

The Cleveland newspapers had a field day with opera at the ballpark. The Plain Dealer headlined their story, “Siegfried in Box, Wagner at Bat - Play Ball! How Operatic Fans Will Yell When Fiery Dragon Dies on First!,” and the News remarked that “not a peanut was cracked by the 10,000 fans who shivered, not in the bleachers, but in the boxes, grandstand and pavilions of League Park when Siegfried played a three inning game of big league opera there Thursday night.”

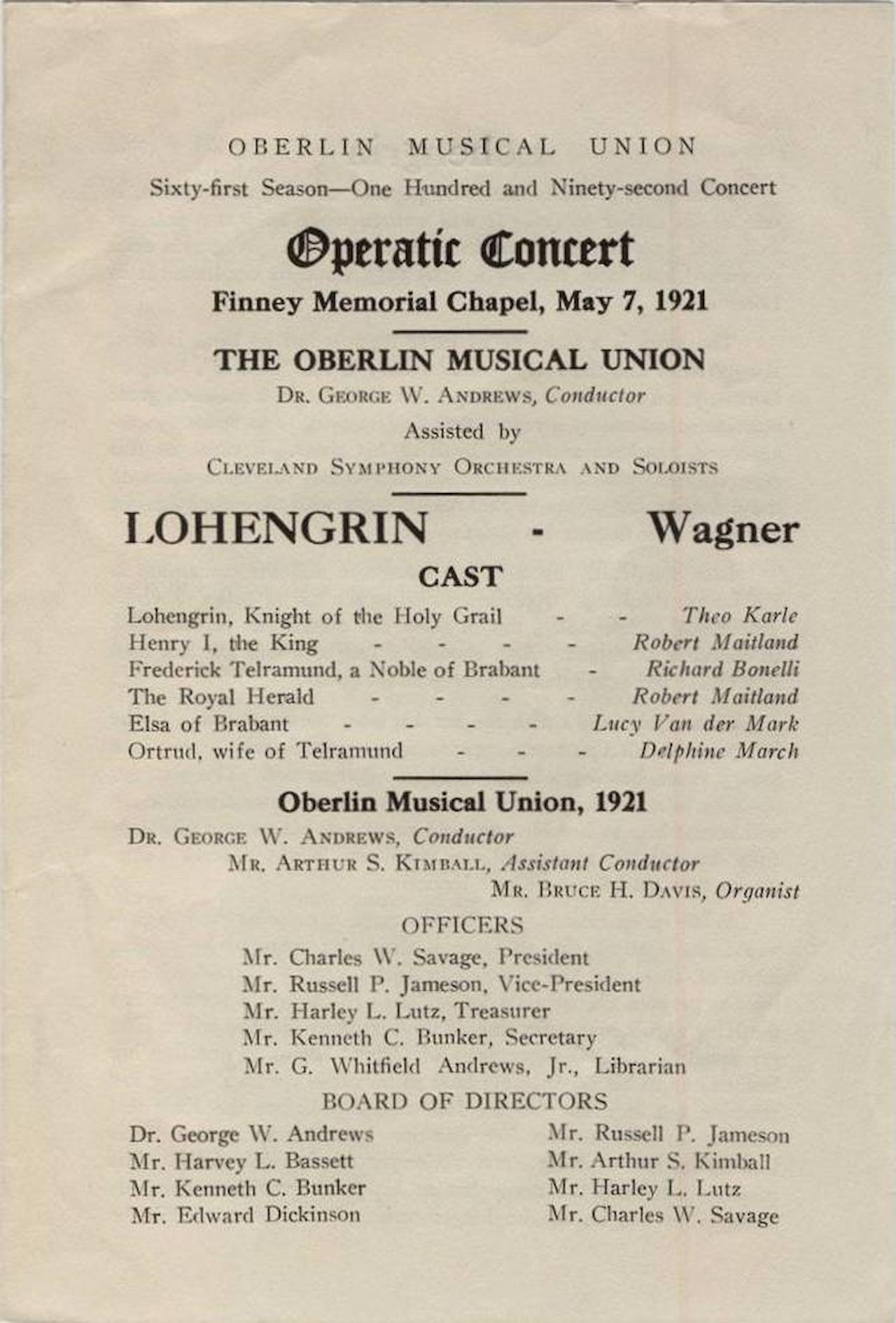

After this big hit, performances of opera in Cleveland continued throughout the 1920s. Then-conductor Nikolai Sokoloff first led The Cleveland Orchestra as a pit orchestra with several well-known choral groups, including the Oberlin Musical Union and the Elgar Choir of Hamilton (Ontario). Unlike the Siegfried performance, these operas were not “fully staged,” but were instead presented as “concert versions”: the music was presented intact, yet without props, scenery, or costumes.

In 1931, opera in Cleveland enjoyed a brief return to the outdoors, and a “Stadium Opera” week was staged in late July at the ballpark before the start of baseball season. This week of productions included complete performances of Verdi’s Aida and Mascagni’s Cavalleria Rusticana, and involved over 1,500 participants on stage, including several members of The Cleveland Orchestra. The events drew over 90,000 spectators each paying two bits to two dollars for their tickets. Though the week of “Stadium Opera” was repeated again in 1932, it was not financially viable enough to continue in subsequent years.

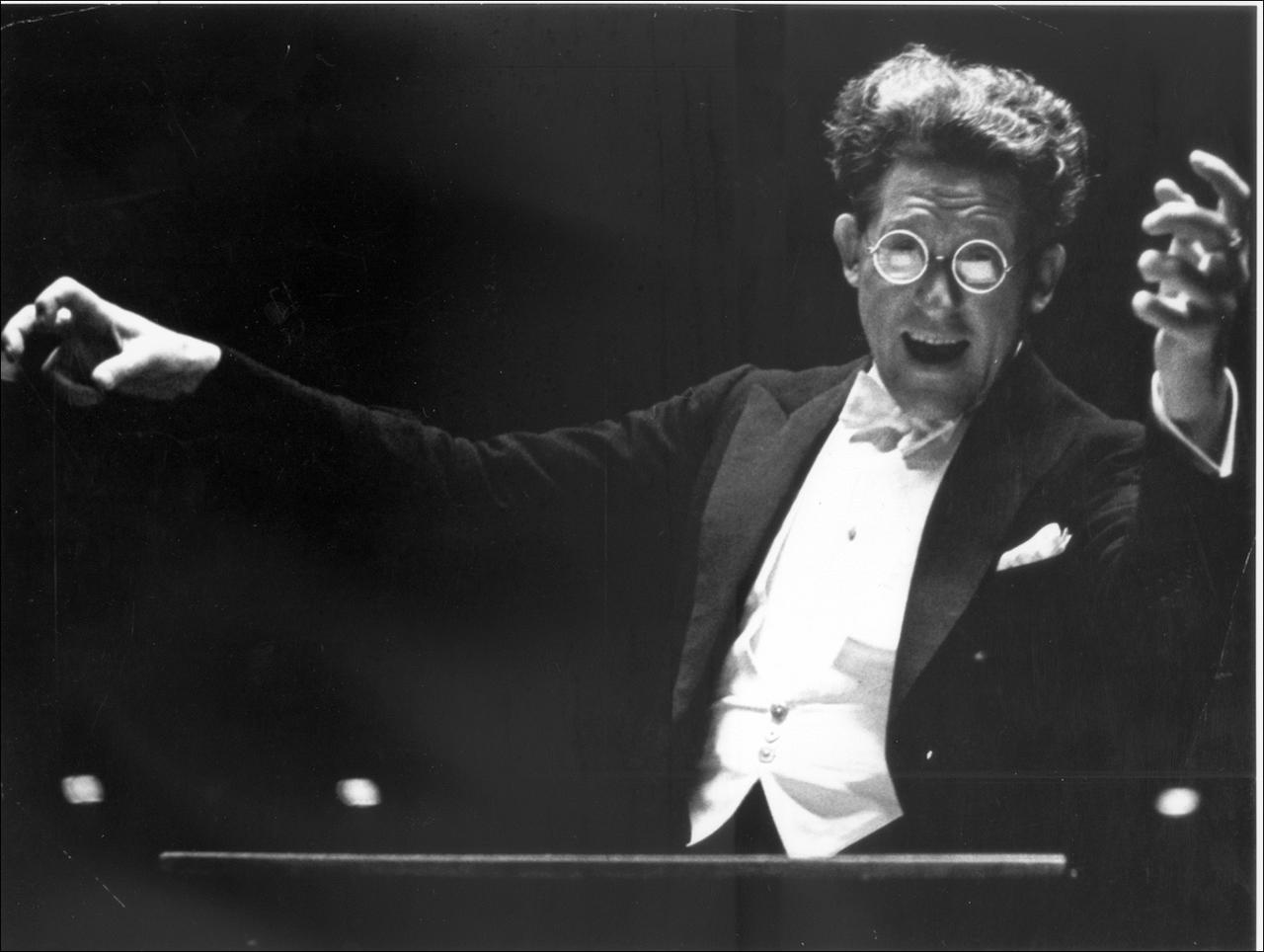

During the years of the depression, the Metropolitan Opera and other touring groups stopped visiting Cleveland due to financial reasons. To keep opera alive in Cleveland, the Musical Arts Association gave Cleveland Orchestra conductor Artur Rodzinski a large budget for presenting operas at Severance Hall. And Rodzinski did not disappoint: fifteen fully-staged operas were presented at Severance Hall within the span of five years! For these productions, the Orchestra played in Severance Hall’s orchestra pit, and singers performed on the main stage.

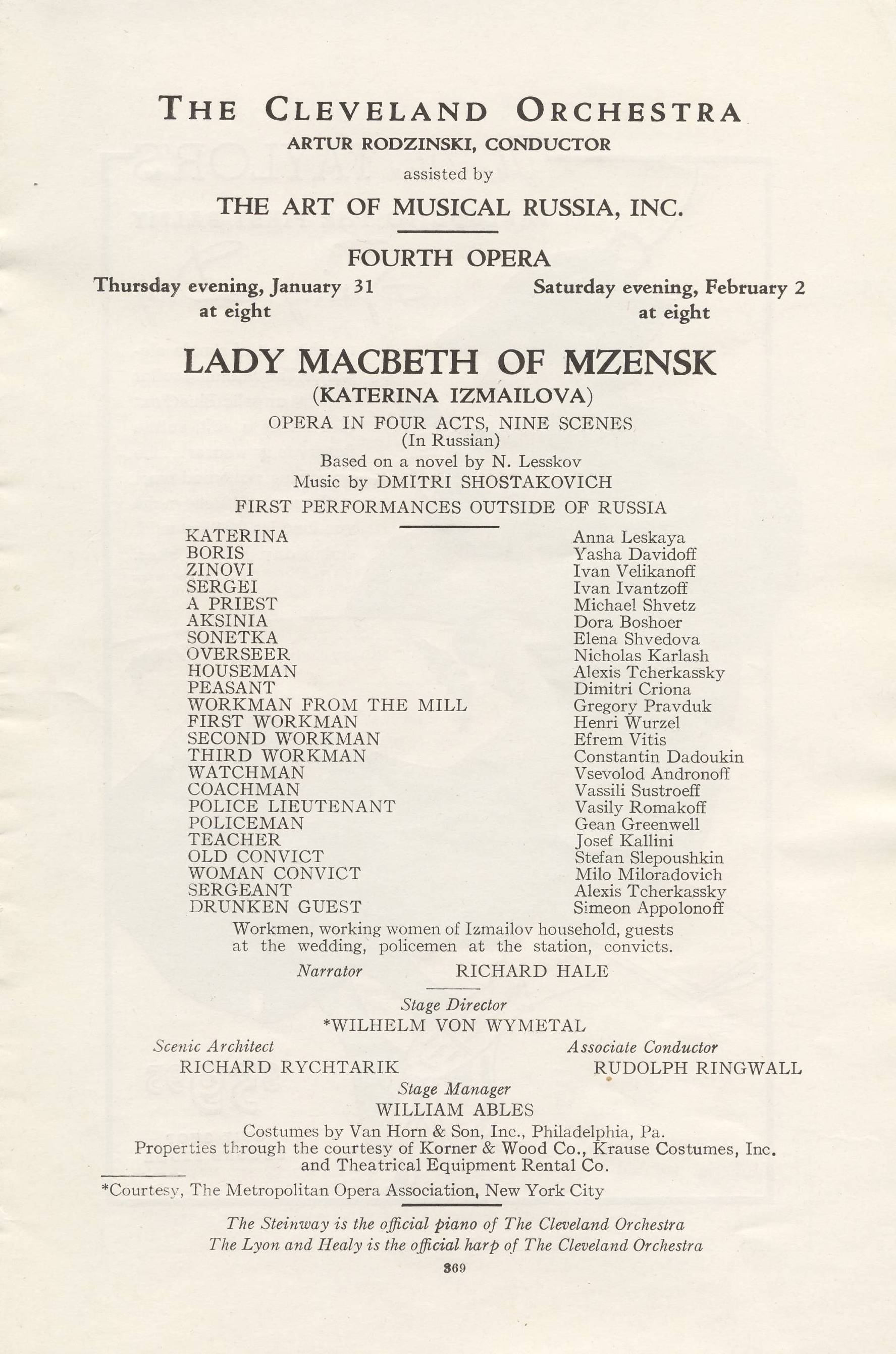

Rodzinski began to collaborate with Wilhelm von Wymetal and Richard Rychtarik in 1934 to produce fully-staged operas at Severance. Formerly a producer at the Vienna Opera, Wymetal had worked with such artistic greats as set designer Alfred Roller and conductor Gustav Mahler. He moved to America in 1921 when he began working at the Metropolitan Opera. In the 1930s, he produced six of Rodzinski’s operas in Cleveland with Richard Rychtarik as his assistant. Rychtarik worked on the majority of Rodzinski’s operas as “scenic architect,” and later moved to New York where he became the principal set designer for the Metropolitan Opera.

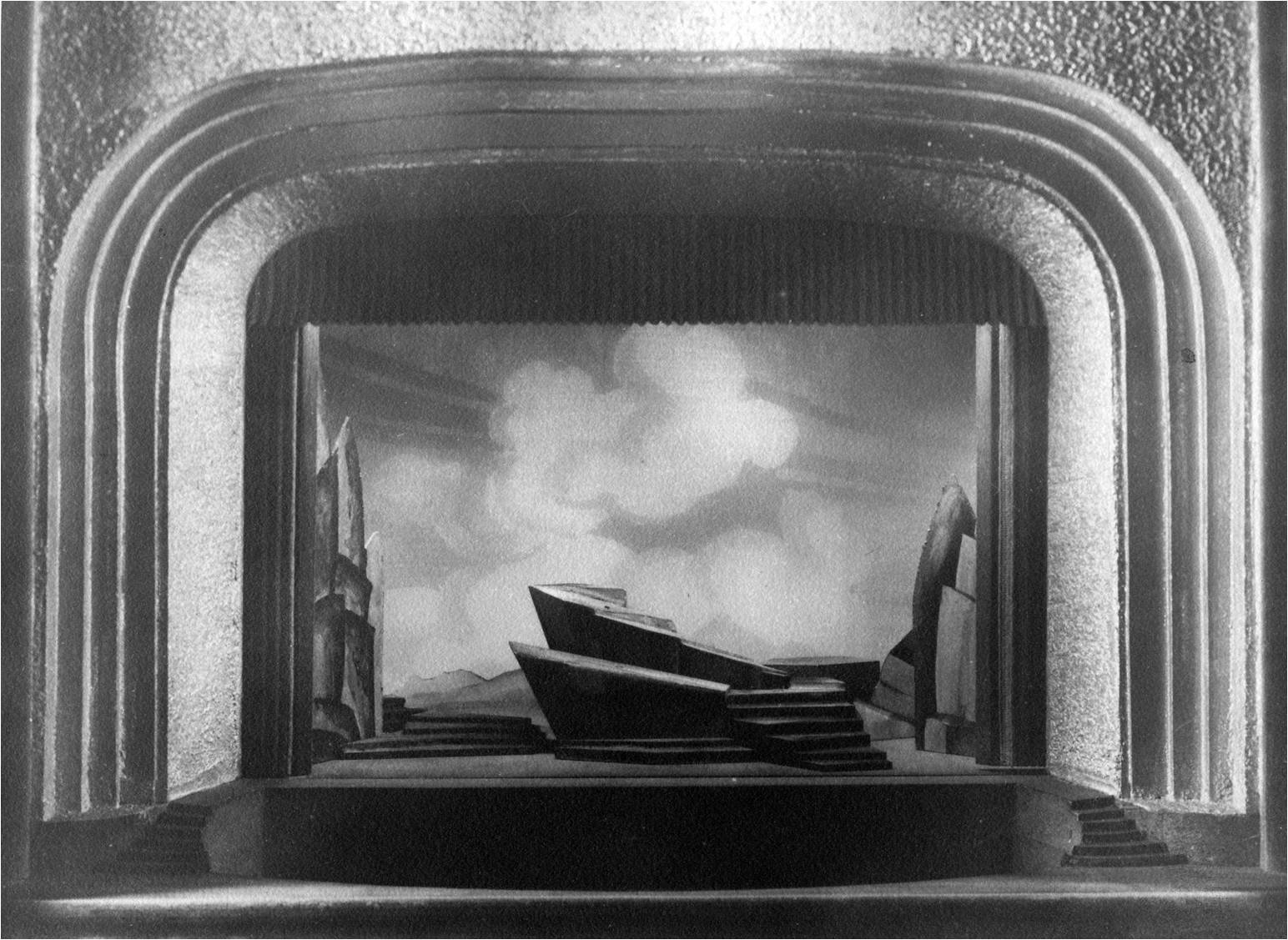

Rychtarik created a maquette (small-scale model) for each of The Cleveland Orchestra’s operatic productions under Rodzinski, and it is amazing how closely the models resemble the scenery of the actual performance!

Wymettal, Rychtarik, and Rodzinski kept Cleveland on the cutting-edge of opera in the 1930s. Rychtarik stated in a 1935 interview that “the modern trend in plays and operas especially, is away from the ‘painted’ realism of yesterday. It is striving more and more for the ‘natural’ realism, such as has been produced in the last few years and last few operatic productions at Severance Hall.”

Cleveland audiences received Rodzinki’s opera productions with great enthusiasm. In the 1934/35 season alone, six fully-staged operas were offered as part of the regular concert subscription series. The national publication Musical America even noted that “The Cleveland Orchestra has always been noted for its enterprise. In its decision to give opera on the highest plane it has challenged the attention of musical institutions everywhere.”

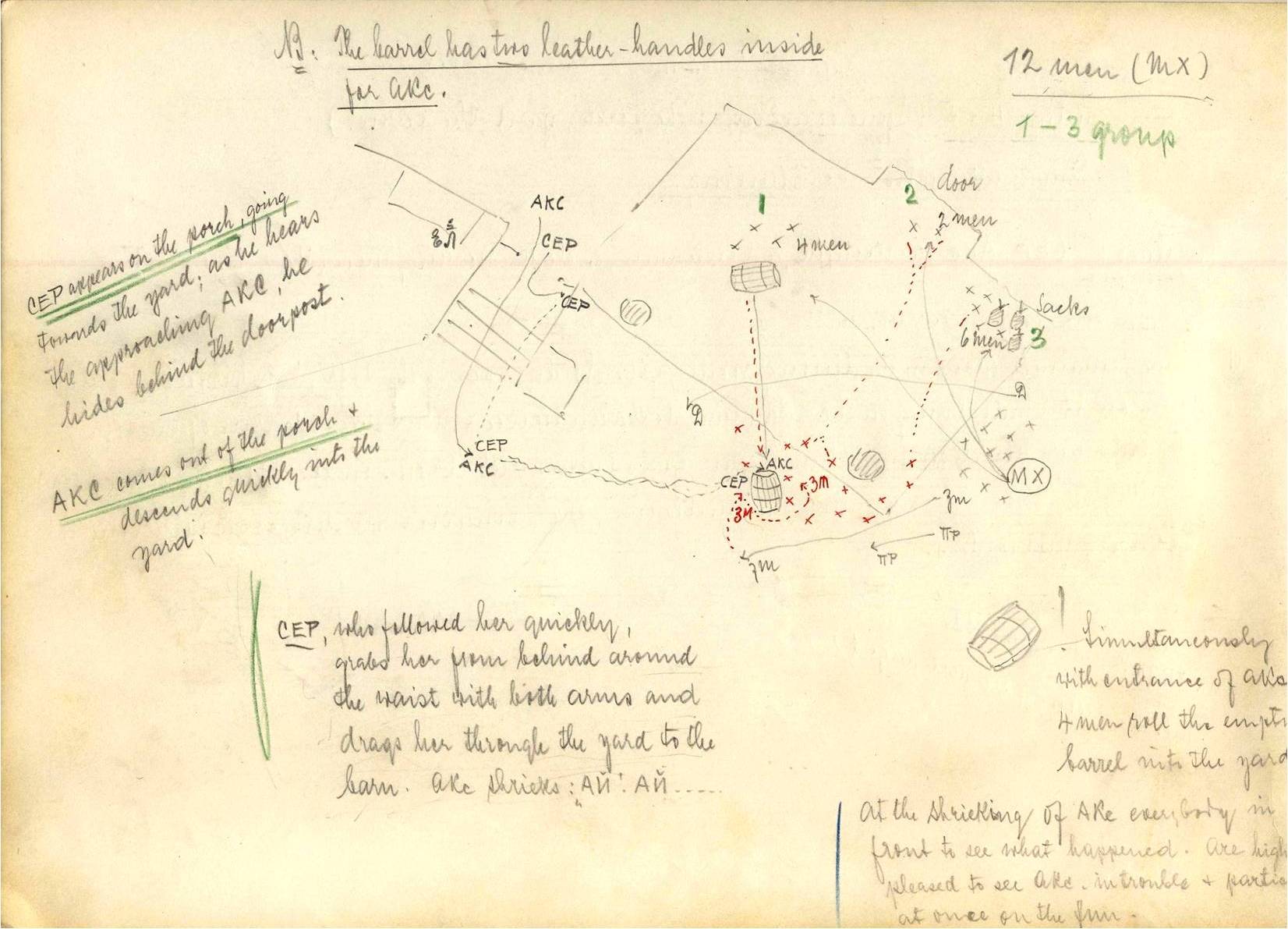

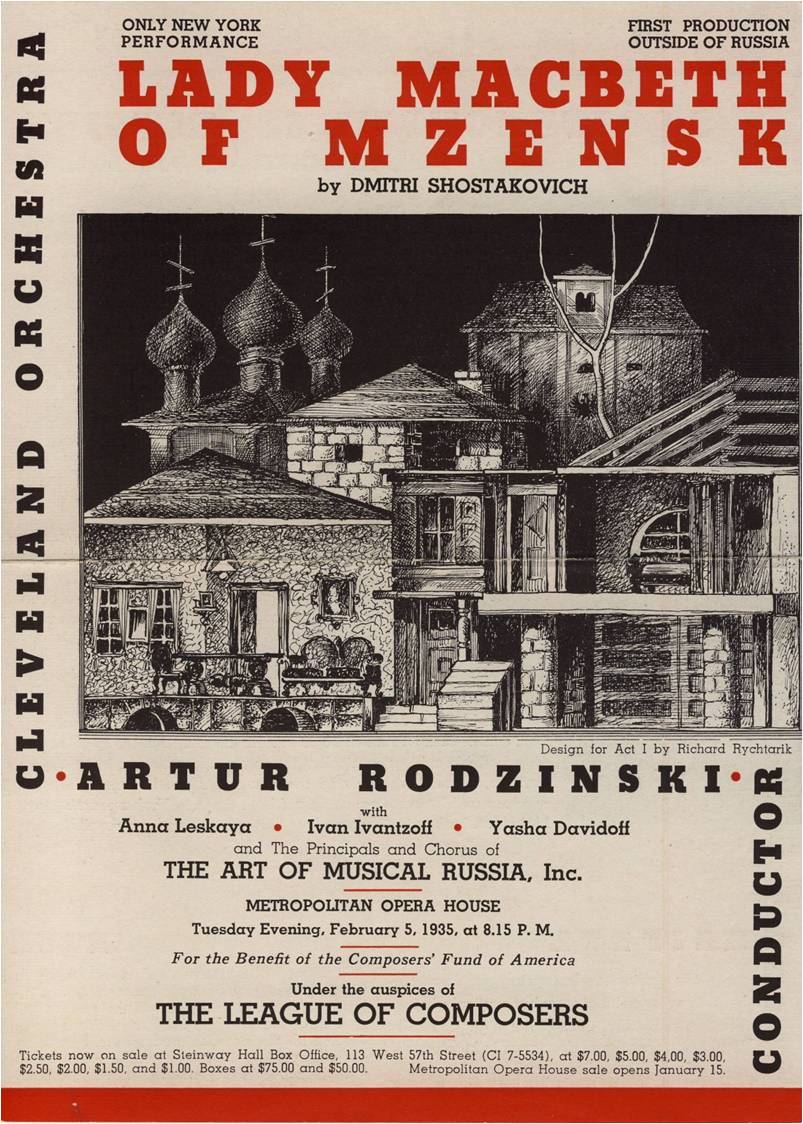

Perhaps the most significant operatic performance during the Rodzinski years was the United States premiere of Dmitri Shostakovich’s Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk. During a trip to the Soviet Union in the summer of 1934, Rodzinski saw the opera performed seven times. He made notes of the opera’s lavish settings during his numerous attendances and conferred with the young Shostakovich to get firsthand information concerning other details. By the end of the summer, Rodzinski was so moved to claim the piece’s American premiere for Cleveland that he outbid conductor Leopold Stokowski for the privilege of performing the opera. When Rodzinski returned to Cleveland, his travel trunks bulged with most of the original manuscripts of Lady Macbeth written in Shostakovich’s own hand.

It took the combined efforts of Rodzinski, the American ambassador, William C. Bullitt, and Newton D. Baker, former Secretary of War, to persuade Soviet officials to allow Shostakovich’s work to be “exported” to the capitalistic world. Rodzinski discusses the experience of trying to leave Leningrad with the manuscripts in a WTAM radio interview on October 10, 1934:

The interviewer begins: “You are putting Cleveland on the musical map in a big way securing the American premiere of this Russian Lady Macbeth. How did you succeed in getting it?”

Rodzinski responds: “Through Mr. Newton D. Baker’s kind recommendation, I met Ambassador Bullitt, who was a wonderful help, for he was so excited over the opera he did everything he could. He attended almost as many performances as I did. You can’t imagine all the interviews, all the details we studied. You see, the product of a Soviet artist belongs to the state, so my dealings were with the high officials of the Soviet Government. It was fortunate I could speak some Russian!

At Leningrad I was ready to board the plane for Danzig with part of Shostakovich’s precious manuscript and some drawings for stage settings – with crosses, circles and dotted lines on them. The big customs officer found them in my luggage. He looked ominous and sternly said, “We will keep these. For all we know, these may be drawings of fortifications, the placement of guns and guards.” Such a business! Here was the work of my whole six weeks to be snatched away! My heart stopped beating! It took me more than one hour to persuade and explain – and finally he let me take them!”

In January of 1935, The Cleveland Orchestra staged Lady Macbeth at Severance Hall. People traveled from as far away as California to hear the American premiere of the opera, and George Gershwin was among the celebrities in the audience. After the performance, Herbert Elwell of Plain Dealer wrote that “surely nothing quite like it has been heard here… But as to the reaction of the audience which packed the house to the door, there can be no doubt. Its members were shocked and stimulated simultaneously. They tittered and gasped. They recalled principals time after time, and when Rodzinski appeared at the beginning of the third act, applause broke into a deafening roar.” The production was later taken on the road to New York, and The Cleveland Orchestra became the first “visiting opera team” to perform at the Met, as they were called by the press.

It is extremely fortunate that Rodzinski was able to take his sketches with him when departing Russia. On January 28, 1936, Stalin attended a performance of the Bolshoi production of Shostakovich’s opera, and left before the fourth act. Two days later, an unsigned editorial bearing the title “Muddle Instead of Music” appeared unexpectedly in the government newspaper Pravda. An uncompromising attack on the opera, it equated the piece’s perceived flaws with “leftist distortions” in the other arts, contrasting it with the realistic, wholesome character of the “true” art demanded by the people. The opera was repressed and disappeared from the repertory, not to return for nearly 30 years -- and then only after Stalin’s death, and in a sanitized, revised version. Had Rodzinski not stuffed his travel trunks with the manuscripts documenting his conversations with Shostakovich, one wonders if the original production could have been restored!

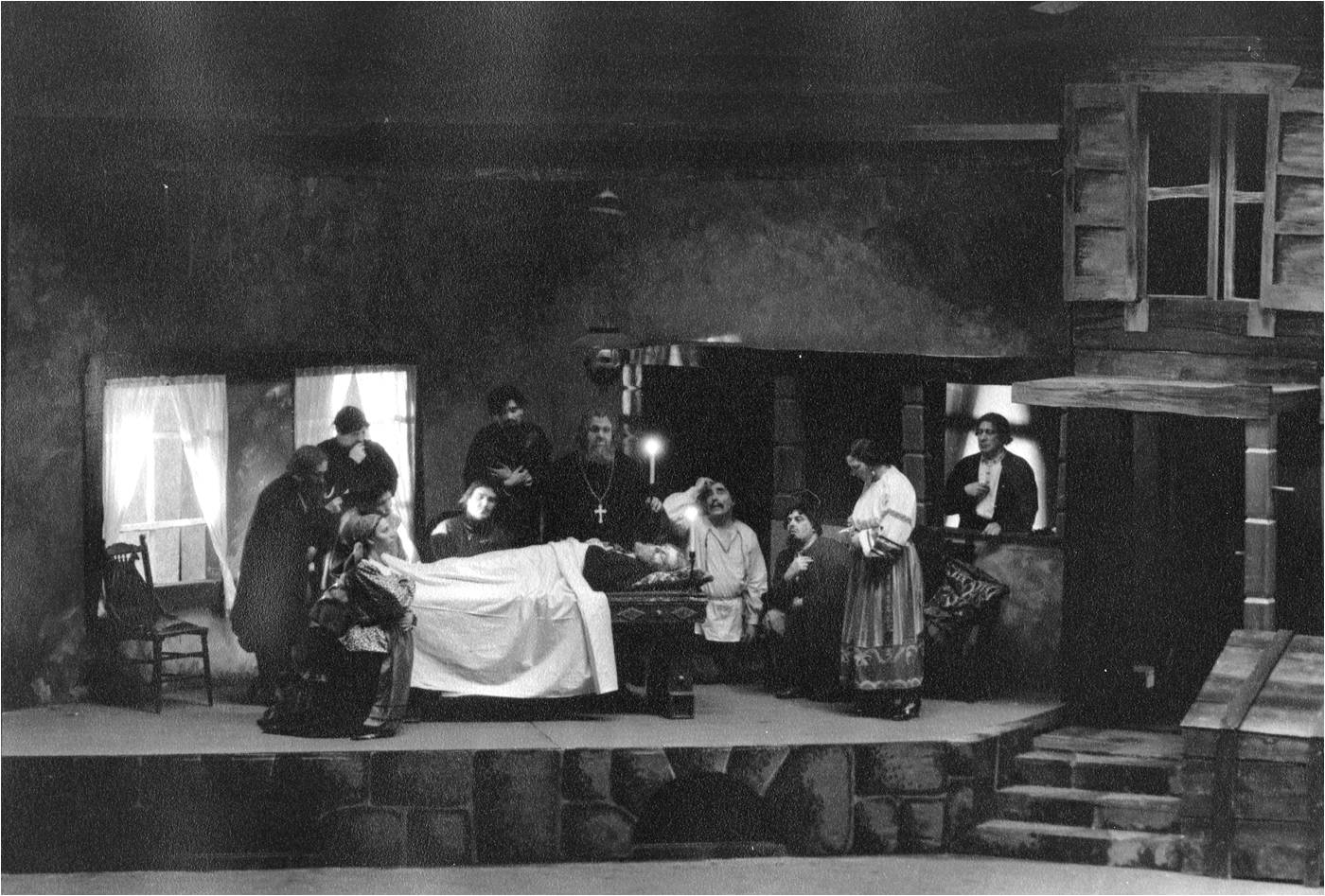

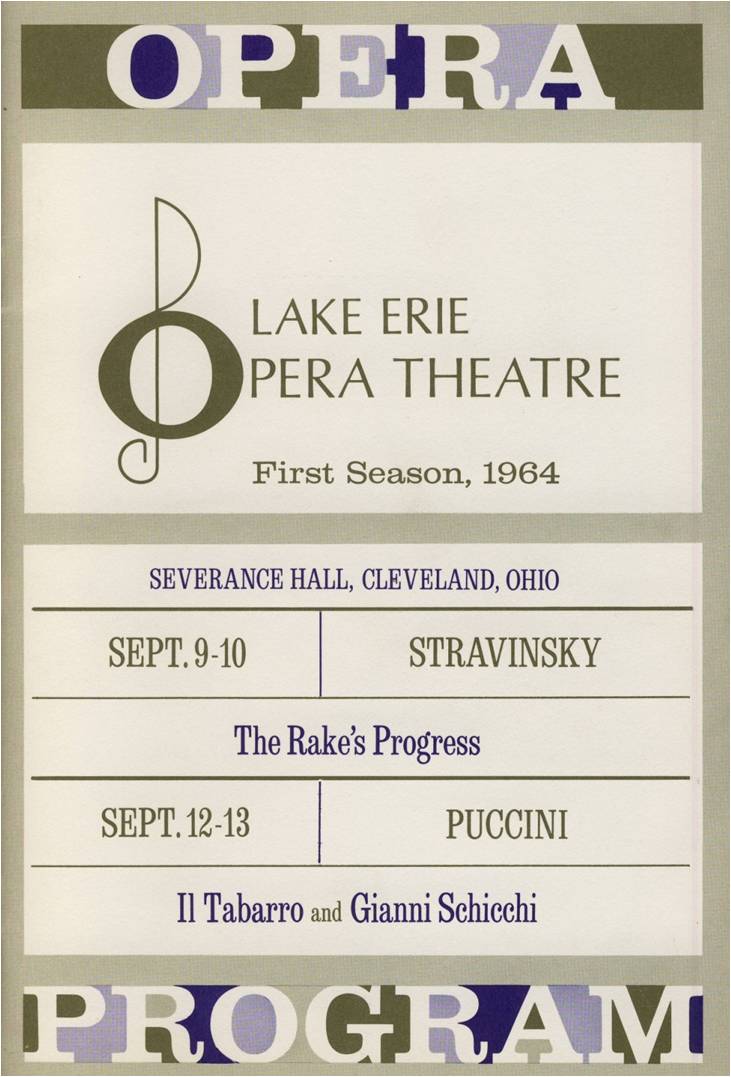

The Great Depression and the years during and after World War II led to the end of fully-staged operatic productions at Severance, but opera returned to the hall in the 1960s when The Cleveland Orchestra and twelve other local arts organizations came together to create the Lake Eerie Opera Theatre (LEOT). This project presented new and unfamiliar operas to Cleveland audiences at Severance Hall before the start of the official Orchestra season. Among the operas presented were fully-staged versions of Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress, Prokofiev’s The Love for Three Oranges, Britten’s Albert Herring, and Poulenc’s Dialogues of the Carmelites.

In 1985, The Cleveland Orchestra returned to outdoor opera productions with performances at Blossom Music Center under the direction of Christoph von Dohnányi. Staged versions of Mozart’s The Magic Flute and Lehar’s The Merry Widow were presented, as well as some concert productions at Severance.

Franz Welser-Möst has led annual opera performances at Severance during his tenure in Cleveland, re-establishing the Orchestra as an important operatic ensemble. Following six seasons of opera-in-concert presentations, he brought fully-staged opera back to Severance with a three-season cycle of the Mozart-Da Ponte operas in Zurich Opera productions.

Beginning a series of innovatively staged operas was The Cleveland Orchestra’s production of Leoš Janáček’s The Cunning Little Vixen as part of the 2013-14 season. This performance was groundbreaking in more ways than one: the staging for this “digitally-animated opera” was created specifically for Cleveland Orchestra performances of the work, and the set was made up of three 26-foot screens upon which animation was projected. The characters of the opera were mostly animated, and cutouts in the screens let them adopt the heads of human singers at times, melding animation with reality. The opera was also done in the Centennial season (2017-18) in Cleveland and in Vienna, Austria.

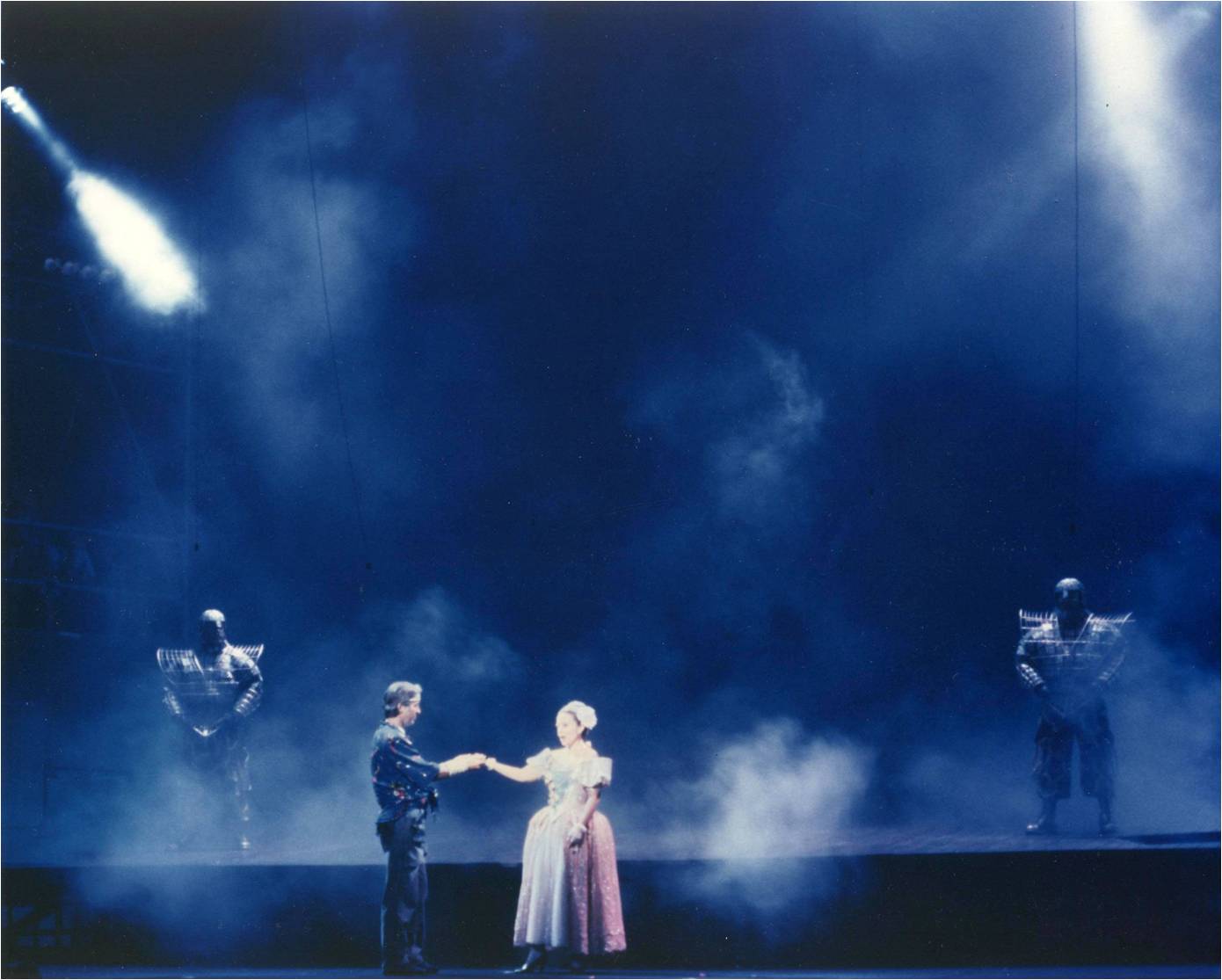

The Cleveland Orchestra continues to showcase their mastery of the genre. In May 2015, The Cleveland Orchestra performed a staged version of Strauss’s Daphne, for which Severance was transformed into a “tableau of nature,” with artificial grass on stage and a large orb alternately representing the sun and moon. In 2016, the opera feature was a double bill of opera and ballet with Béla Bartók’s The Miraculous Mandarin and Bluebeard’s Castle in partnership with the Joffrey Ballet. In May 2017, a fully staged production of Debussy’s Pelleas et Melisande was presented to wide acclaim. This production featured a large glass box on stage that was transformed with fog and lights to match the various scenes of the opera.

The centennial season featured two operas: The Cunning Little Vixen in fall 2017 and Richard Wagner's Tristan and Isolde in spring 2018. The following year, the orchestra staged a production of Strauss’ Ariadne auf Naxos featuring design motifs of Severance Music Center throughout the production. Opera returned after the pandemic with Verdi’s Otello in concert format.

Building on decades of experience and recent successes, The Cleveland Orchestra aspires to present an opera each season, featuring either works in concert or in fully staged performances that transform Severance into a world-class opera house.

All photographs and audio clips courtesy of The Cleveland Orchestra Archives.