Miss Baldwin’s Opus

The Early History of The Cleveland Orchestra’s Education Programs

By Alex Lawler

The Cleveland Orchestra’s involvement in music education programs is almost as old as the Orchestra itself. The first outreach concert that the Orchestra performed was on January 28, 1919 at West Technical High School in Cleveland, and a few short years later in 1921, began bringing school children to Masonic Hall (the Orchestra’s rented home before the completion of Severance Hall in 1931). Initially, these concerts were conducted by Nikolai Sokoloff (the Orchestra’s first conductor) and Arthur Shepherd (assistant conductor 1921-22 to 1925-26, sole children’s conductor 1926-27 to 1927-28) until Rudolph Ringwall (assistant conductor 1926-27 to 1933-34, associate conductor 1934-35 to 1955-56) took over these performances starting in the late 1920s. However, the Orchestra’s education efforts at this point, as Adella Prentiss Hughes described, were “hit or miss,” due to the lack of professional music educators both in the Cleveland Public School District as well as at The Cleveland Orchestra. Hughes and others sought to find a qualified candidate to spearhead a new direction in their educational efforts, and in 1929 their search ended with the arrival of Lillian Baldwin.

Lillian Baldwin (1887-1960) was born into a musical family and originally trained to become a singer. Sometime in the late 1910s she decided that music education was more her forte and enrolled at Columbia University, earning her Bachelors and Masters. Baldwin was attracted to the idea of working in Cleveland because of the presence of The Cleveland Orchestra, and Adella Prentiss Hughes was attracted to Baldwin because of her bold and comprehensive approach to music education. Baldwin envisioned a comprehensive and inclusive music education program that focused not just on musically gifted kids but any child willing to learn. She created a range of age-specific study materials for each concert, and had them distributed throughout the Cleveland Public School District. Study over a semester would culminate in a live performance by The Cleveland Orchestra at Severance Hall.

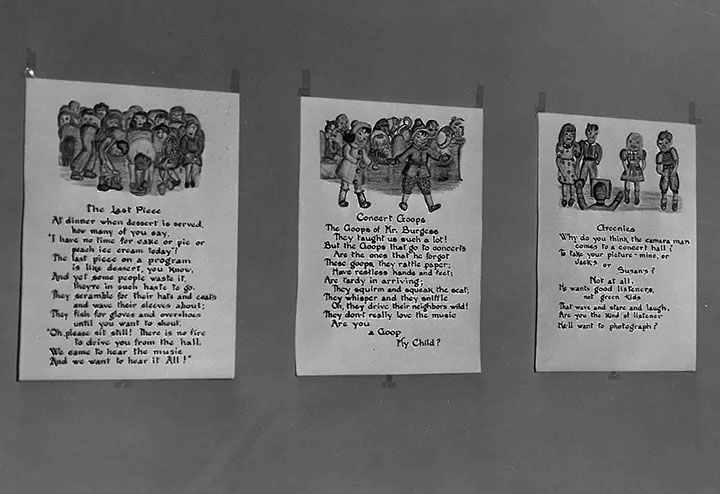

Her methods and curriculum combined thorough structure and organization with whimsy and magic. Deciding that simply telling students “Do’s and Don’ts” of attending a concert would not be effective, she created rhymes which she illustrated to teach students proper concert etiquette. The most unusual thing on record was an incident from 1942 in which she devised an unusual lesson to teach fourth grade students about what a fugue is: she had the director of the Cleveland Public Library, Clarence S. Metcalfe, orchestrate Domenico Scarlatti’s Cat-Fugue (whose main theme was, the story goes, taken from one day when Scarlatti’s cat walked across his harpsichord) for instruments and cats. Finally, Baldwin was insistent on making music available to everyone, and many of her concerts had braille books especially written so that blind children could more easily participate. Baldwin’s efforts later became known as “The Cleveland Plan,” and were imitated by orchestras all over the country, becoming the de facto model for orchestral music education programs.

It has been a little over sixty years since Lillian Baldwin left The Cleveland Orchestra, but her legacy continues on in our continued commitment to our education program. Today, over fifty-thousand people participate in education programming offered in-person and virtually. The Orchestra provides community programming in Northeast Ohio neighborhoods with collaborative performances at local organizations and hands-on music activities at community festivals. Several times per year, students from all around Cleveland are bused to Severance, as they’ve done for over a century, to attend a series of education concerts.

Alex Lawler was an intern for the 2015/16 season in The Cleveland Orchestra Archives.

Want to know more?

Adella Prentiss Hughes’s autobiography “Music is My Life” devotes an entire chapter to The Cleveland Orchestra’s Educational Program. Half narrative, half series of charming anecdotes, you can find the book here at the Cleveland Public Library.

You can view a 2009 WKYC (Channel 3 News) story about one of our Education Concerts (entitled “Meet the Orchestra”) at James Rhodes High School here. Additionally, you can also watch a short excerpt of our educational concert series for young children (entitled “Musical Rainbow”) here.

All photographs and audio clips courtesy of The Cleveland Orchestra Archives and WKYC (Channel 3 News).