A “Martyred Opera” Comes to Cleveland

Perhaps no cultural history informs the modern political trajectory as well as that of opera. From its inception, governments and subversive factions alike have capitalized on the opera as a vehicle for allegorical commentary on urgent contemporary issues. Recall the self-aggrandizing spectacles by Jean-Baptiste Lully of Louis XIV’s court or Mozart’s La Nozze di Figaro, which sets to music Lorenzo da Ponte’s harsh criticism of class inequality on the brink of European revolution. This is all to say that to study opera without the context from which it emerges is to miss, in large part, its aesthetic and thematic significance.

Perhaps no institution has capitalized on the arts’ political valence to the extent of Soviet Russia’s Communist regime. Artists were yoked by the close scrutiny of government committees dedicated to curating cultural products that advanced the government’s campaign as well as censoring those which did not. A case in point is Dmitri Shostakovich’s 1934 Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk, for which the composer became the subject of harsh polemics by state critics and even came to fear for this life. In his memoires, Shostakovich relays the events of a 1936 performance of the opera at the Bolshoi during which Stalin stood and left before the final curtain. Cued by the Premier’s overt gesture of disapproval, audiences departed the theater in silence and, within days, Pravda, the Communist Party’s official arbiter, issued a polemic lambasting the work for "tickling the perverted taste of the bourgeoisie with its fidgety, screaming, neurotic music.” For Shostakovich, the evening marked the beginning of a life lived in terror.

Less than a year later, on the evening of January 31, 1935, Lady Macbeth enjoyed its U.S. premiere on the stage of Severance Hall under the direction of Artur Rodzinski. While creativity under Soviet sanctions has been a popular area of study for historians, little has been said of the process by which these works arrived in geographically and ideologically distant places as objects of aesthetic beauty. Indeed, it was not without difficulty that Shostakovich’s opera came to Severance’s stage. But something within the work transcended its political message enough to appeal to Rodzinski, who was determined to return to Cleveland with the manuscript in hand, confident that American audiences would enjoy the work no less. And it might be that the very popularity Shostakovich’s work enjoyed in the United States following its Cleveland premiere explains its precarious position in Soviet aesthetics.

What was it of Lady Macbeth that so obviously threatened state ideologies? After all, the opera’s subject matter, a blatant attack on pre-Soviet society, had all the credentials to bolster Stalin’s campaign. The story is that of a merchant woman, Katerina Ismailova, who is driven to madness by the social tensions of class stratification in Czarist Russia, killing her father-in-law, husband, and nephew. In his critique of the New York Metropolitan Opera’s 1995 revival of Lady Macbeth, musicologist Richard Taruskin pursues subversive gesture within the opera. Some historians, he notes, have argued that Stalin’s government perceived danger in the madwoman’s response to her environment; that, inasmuch as it defamed anti-communist ideals, it provided a model for political unrest antithetical to the solemnity by which the regime sought to subjugate its constituents. For Taruskin, however, it is the opera’s music, which so aptly depicts the eponymous madwoman’s desires, pleasures, and internal disorder, that betrays the composer’s own personal identification with her tortured psyche and surely disturbed government leaders in the audience.

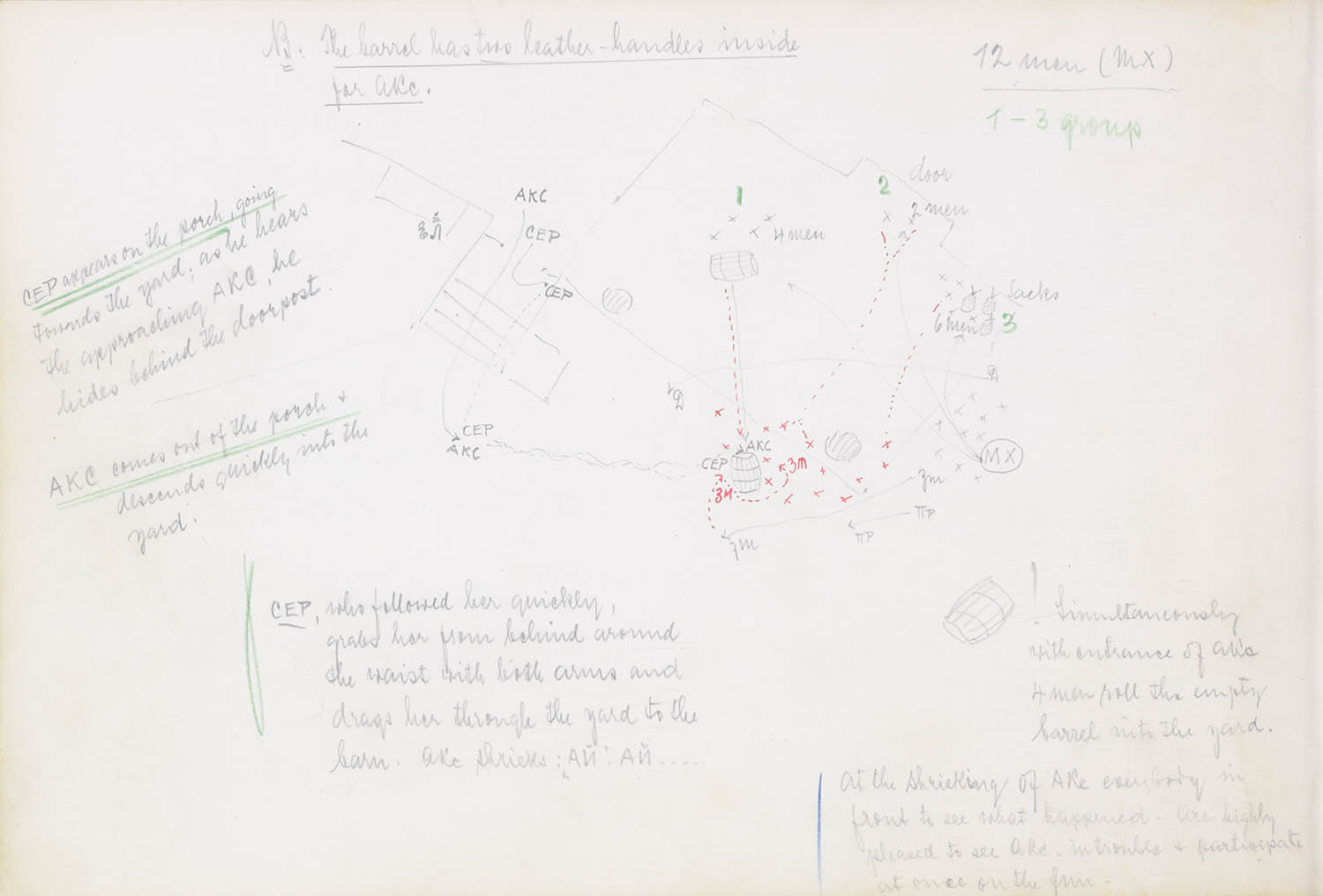

It was this very element of humanism that so appealed to Rodzinski when he attended several performances of Lady Macbeth during a 1934 trip to Russia, “the most moving of operas” and “Shostakovich’s personal masterpiece,” as he wrote. Rodzinski went to great lengths to bring the manuscript with him to Cleveland, a feat complicated by the U.S.S.R.’s claims to ownership of its constituents’ intellectual property. Aided by Ambassador William Christian Bullitt, Rodzinski secured the rights to the score, only to have it confiscated upon leaving the country when a border patrol agent confused its stage sketches for battle plans. After hours of negotiation, Rodzinski was permitted to leave with the manuscript in hand and the opera premiered in the season that followed.

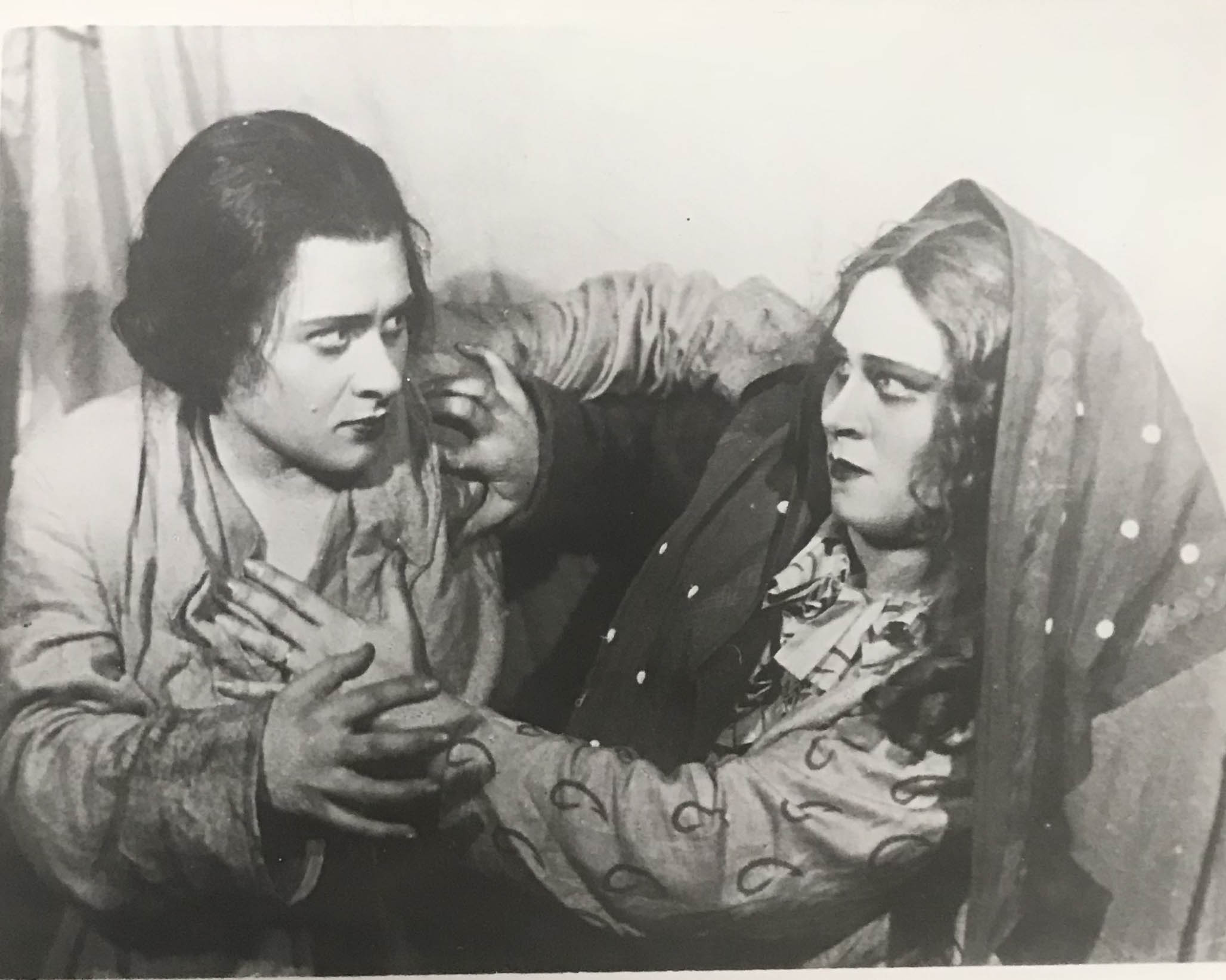

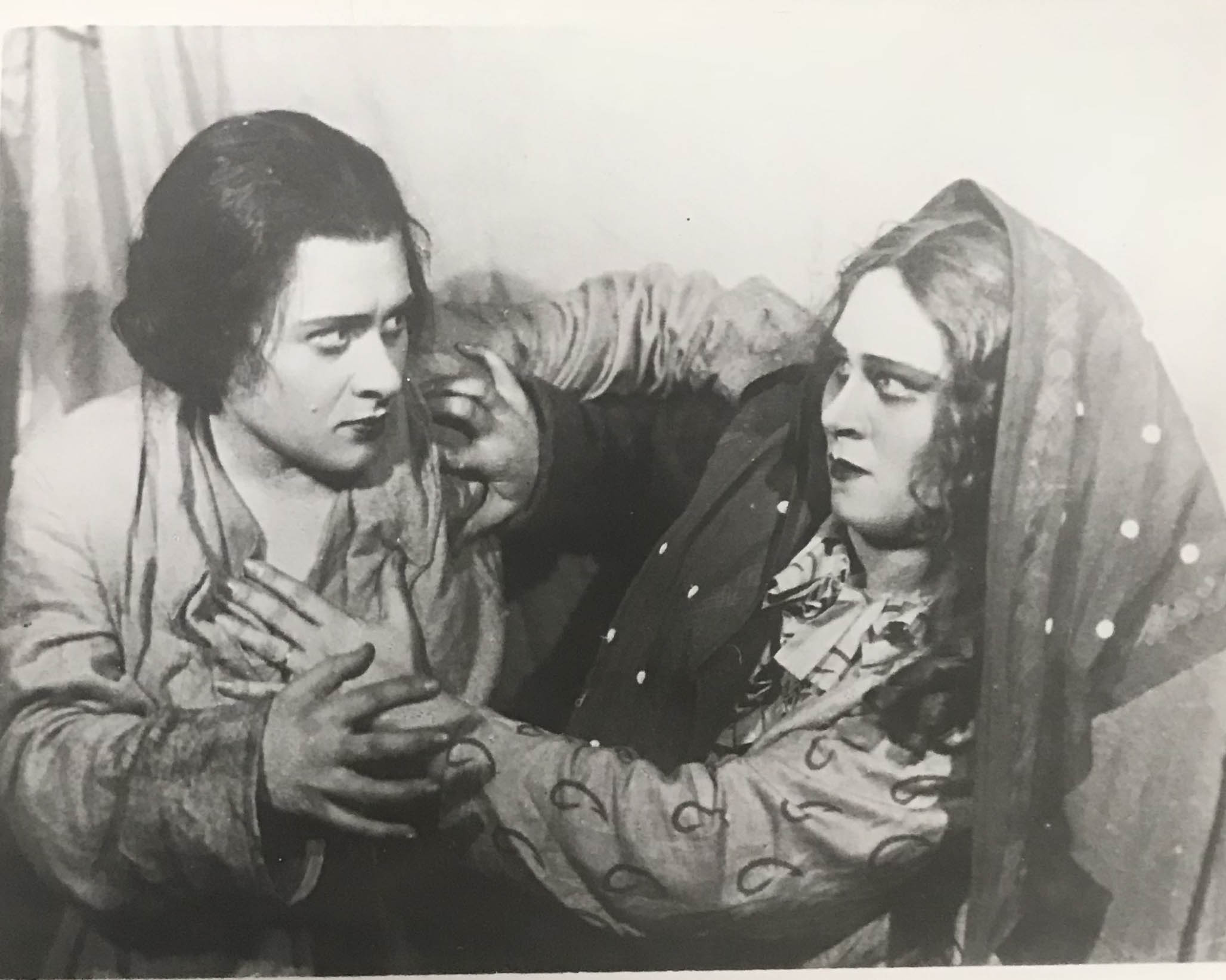

The press eagerly followed the opera’s preparations and promised a “work of unrivaled Russianness” (Plain Dealer, 1934). Evidenced by an impressive body of stage directions and designs held in The Cleveland Orchestra Archives, a great deal of attention was given to setting the opera in a manner that did justice to its themes and remained true to the work’s world premiere. Stage designer Richard Rychtarik envisioned a dark and tenebrous stage on which to set the tortured, eponymous madwoman, a close reproduction of the setting employed in the Leningrad performances at which Rodzinski had been present. One critic for the Plain Dealer lauded the stage as “sketchy in design—equipped with transcendental scenery that suggested, rather than pictorialized idealistically.” And on all accounts, audiences were impressed by the emotional cohesion of the production, held in “the thralls of a composer who imposes his own suffering on Katerina and the listeners alike.”

It is obvious from critical responses that American audiences perceived in the production not only tumultuous subject matter, but a creative voice that closely identified with it and musically reveled in it. That is, its story line was only a point of departure to convey a world of uneasiness not at all unfamiliar to Shostakovich. It is this very element of self-reflection in Lady Macbeth that led Taruskin to name the work a “martyred opera,” or a sacrificial, iconoclastic work unsuccessfully guised with propagandistic themes. Within two years of the fateful Leningrad premiere, power to censure was consolidated to the Central Committee; and Shostakovich’s opera was officially proscribed. Indeed, it was only through the cracks of the early regime’s fragmentation that Lady Macbeth narrowly crossed U.S.S.R boarders and arrived in Cleveland. In Soviet Russia, it became the object of a general denunciation of Shostakovich’s music. In the United States, however, it enjoyed widespread popularity as the symbol of artistic beauty born of socio-political hardship. Whether it was this very quality that saw to its silencing at the hands of U.S.S.R. leaders cannot be answered with certainty. In any case, The Cleveland Orchestra had introduced a work that could not be contained to any time, place, or ideology.