Remembering Ravel’s Conducting Debut in Cleveland

By Kate Rogers (April 2015)

Many great composers of the twentieth century have come to Cleveland at the invitation of The Cleveland Orchestra to conduct concerts of their own music. While all of these visits have been memorable to Cleveland’s musical community, surely one of the most unforgettable was the time that Maurice Ravel came to town.

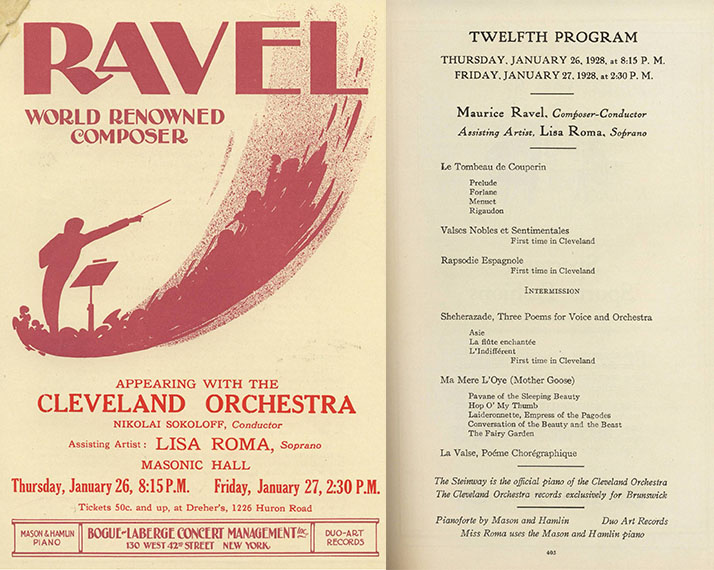

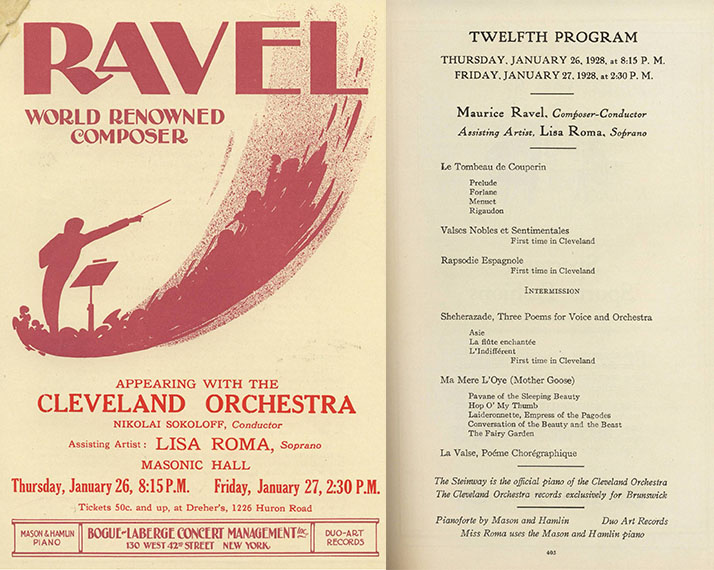

Ravel visited Cleveland during his first American tour in 1928 at the age of 52. The Sixth City (as Cleveland was known in the 1920s) was the third stop on his list, right after Boston and New York. While in Cleveland, Ravel gave a lecture and a chamber music concert at the Cleveland Museum of Art, and led performances with The Cleveland Orchestra on January 26 and 27 at Masonic Hall.

Right: Program from Ravel’s concert with The Cleveland Orchestra, 1928

At the museum concert, Ravel performed a selection of his piano pieces and vocal compositions with soprano Lisa Roma. The composer also presented an essay about his forthcoming second sonata for violin and piano, focusing on how the American blues tradition had influenced his composition of the piece. Much of the music presented at Ravel’s museum concert had not been heard in Cleveland before, and various newspaper reviews of the performance describe the confusion of the audience. James Rogers of The Plain Dealer describes Ravel’s audience at the museum as “friendly but somewhat puzzled,” and likens the audience’s experience with Ravel’s unfamiliar compositions as a journey to “an undiscovered country.”

After this “puzzling” concert at the museum, Ravel conducted two performances of his orchestral works with The Cleveland Orchestra. Unfortunately, not everything went as planned in the first rehearsal, and Music Director Nikolai Sokoloff was not at all impressed with Ravel’s behavior or conducting technique. Sokoloff recounted Ravel’s visit in detail in his unpublished memoir:

“…. There were one or two composer-conductors whose appearances with the Orchestra generated something less than pleasure. One of these was Maurice Ravel.

I always attended the first rehearsal in order to introduce the composer to the orchestra and see that everything got started smoothly; also, to be sure that the composer could handle the assignment. That Monday morning I was at Masonic Hall before ten o’clock…. I had asked Carlton Cooley, who passed the Statler Hotel on his way to the rehearsal, to stop there and pick up Ravel. Ten o’clock came and went and no Ravel; also no first violinist. I couldn’t just let the orchestra sit there and wait, so I started rehearsing. About twenty minutes past ten, Ravel strolled in and a somewhat white and shaken Cooley took his place in the orchestra.

Ravel was greatly surprised that we had started without him, but I explained that, in America, we had strict union regulations and every minute of rehearsal time counted. “Oh, I didn’t know,” he said airily. “In France we are not so particular.”

I reiterated the importance of using every available minute of rehearsal time. “Well, well,” he murmured, “I shall try to be prompt tomorrow.” With that he stepped up to the stand, raised it almost up to his chin, and started rehearsing.

I saw immediately that his technique was simply abominable; the musicians couldn’t understand a thing he did. In the first place, he was very short and, with the raised stand (he must have been extremely nearsighted and too vain to wear glasses) the men could hardly see him, in spite of his unusually long neck. He did not use a baton, but pressed his fingers together so that his hand resembled nothing so much as the head of a snake, and this he weaved and waved about so indiscriminately that nobody could understand what he wanted. Nor did he seem to know where any section of the orchestra was located.

To make matters worse, he hesitated constantly and, of course, as he did so, the orchestra played more slowly. After a while, he would say, “No, no, no – it is much too slow!” I felt like saying, “Well, go ahead, they will follow you!” But he seemed incapable of going ahead….

It was both messy and ghastly, but there was nothing to be done. He had been announced to conduct and conduct he would. He was apparently unaware of his utter incompetence and, after the rehearsal, assured me that I need not worry, everything would go beautifully. Of this he failed to convince me, so I decided not to go away for fear something would go shockingly wrong that I would have to conduct all, or at least part, of the concert.

After the rehearsal, when Ravel had gone to my dressing room to freshen up, Cooley confided to me that the reason they had been late was because Ravel had become entangled in a hairnet which he wore at night to keep his hair in place. When Cooley had arrived at the hotel and had sent his name up, Ravel had asked that he come to his room. There Cooley found him in front of the mirror, completely entangled in the hairnet from which his nearsightedness made disentanglement impossible. Even Cooley had difficulty getting him out of it!

I shall never forget the night of the concert. Among other compositions of his, he conducted his Rhapsodie Espagnole, which is a picturesque and brilliant piece. But, as he could never remember where any part of the orchestra was located, he would signal to the right for the violas and find the cellos there, and at one point where the percussion had something stunning to do, he signaled in a totally different direction, with the natural result – a sloppy and indecisive entrance by the percussion section.

The whole concert was terribly shaky and I almost had a nervous breakdown. The audience, appreciating his greatness as a composer, was polite, so he had a certain success. But that was his first and last appearance with us as a conductor. I, for one, couldn’t have lived through a return engagement.”

Despite mixed reviews of his conducting debut with The Cleveland Orchestra, Ravel had great success with his American tour overall. Sokoloff’s memories of Ravel’s conducting experience in Cleveland remind us that even the greatest of composers are still human, and can get stuck in their hairnets from time to time.

Kate Rogers was an intern in the 2014-15 season with The Cleveland Orchestra Archives, during which she was a PhD student in musicology at Case Western Reserve University.

All photographs and excerpts from Sokoloff’s memoirs Courtesy of Cleveland Orchestra Archives.

Looking for more?

Click here to listen to the Radiolab podcast “Unraveling Boléro,” which discusses what happened to Ravel after he wrote Boléro and explores “a strange symmetry between a biologist and a composer that revolves around one famously repetitive piece of music.”