The Cleveland Orchestra Chorus Finds a Hero:

Robert Shaw Makes His Mark

By Dane–Michael Harrison (2024)

“Before my experience in The Cleveland Orchestra Chorus, I had never fully realized the intimate nature of the relationship between a director and his choir. When I applied for an audition I had no idea that Mr. Shaw himself would judge each prospective member individually. I had expected that tedious task to be delegated to a subordinate. But from the moment I rather timidly marched up on the stage and was informed that the sandy-haired, blue-shirted man sitting across the card-table from me was the Robert Shaw, I began to comprehend how completely the Chorus was his creation.”

— Michael Swanson, a fourth-year bass in The Cleveland Orchestra Chorus, writing in 1966

The Cleveland Orchestra’s most formative choral director suffers, to a degree, from overexposure in public memory on account of his eminence in the international choral community, especially during and after his directorship of the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra. Yet relatively few Cleveland natives nowadays would likely recall Robert Shaw’s earlier tenure at Severance Hall, which marked a crucial phase in the careers of both Shaw and The Cleveland Orchestra.

When Music Director George Szell hired Shaw in 1956 as an associate conductor (for the Orchestra) and the Director of Choruses, he was the latest in a succession of musical impresarios who had perceived Shaw’s peculiar ability to hone a group of singers into a choral battery of overwhelming artistic impact. Shaw would work with both professional and amateur choristers over the course of his long career, and he was at special pains to communicate to his amateur singers, like those comprising The Cleveland Orchestra Chorus, his belief in their artistic worth, which he regarded as perhaps greater than that of the average professional musician, because of their lack of mercenary motivation. (The members of the Orchestra’s chorus are not now — and never have been — paid for their contributions to Cleveland’s musical life.)

Michael Charry and Donald Rosenberg, in their respective biographies of Szell and the Orchestra, report how the ensemble was, around this time, becoming firmly established in the international consciousness as one of the greatest orchestras. During their first European tour in 1957, the Clevelanders bowled over audiences and critics in the old countries, many of whom freely conceded that Szell’s orchestra equaled — and perhaps could even eclipse — their more venerable symphonic institutions. Over the course of a decade, from the mid-1950s to the mid-’60s, Shaw accomplished Szell’s assignment in elevating Cleveland’s amateur symphonic chorus to a fearsome artistic caliber.

Born in 1916, Shaw had already begun his precipitate professional rise by the late 1930s (his early career slightly predates the Second World War). His talents were nurtured early on under the auspices of Fred Waring’s radio empire — Shaw’s first big break out of college. That Shaw would eventually graduate to the greenest of musical pastures, by joining forces with Szell in Cleveland, is hardly surprising. His whole career trajectory was a remarkable, willful ascent from the amateur collegiate ensemble to the directorship of another major American orchestra, the Atlanta Symphony.

Already renowned as a choral conductor well before his arrival in Cleveland, Shaw would maintain additional professional activities and commitments during his tenure here, continuing to record with his own professional ensemble, the Robert Shaw Chorale. The popular (and popularizing) instinct evidenced by Shaw’s various projects with his personal chorus (for example, an album of sea shanties with the Chorale’s male voices), shows that he never lost his sense of readily accessible music-making, inculcated in the college glee club settings where he’d got his inauspicious start.

Though the Orchestra’s archives contain quite a few non-commercial, live recordings of Shaw’s performances in Cleveland, his corpus of commercial recordings with the Clevelanders is slight. This would have been due, at least in part, to Shaw’s recording contract with RCA, predating his arrival in Cleveland, which conflicted with the Orchestra’s at Columbia Records. (Ironically, both labels would be subsumed under Sony years later.) One therefore has to do a bit of light digging (along with some imaginative extrapolation) when attempting to piece together a sonic portrait of Shaw’s Cleveland years. Shaw was able to record commercially with musicians from the Orchestra and Chorus, but the contractual snags resulted in the musicians’ professional affiliation being somewhat euphemized when they appeared on the RCA label under his direction.

Shaw’s principal commercial recording with the Clevelanders is not entirely representative of the scope of his conducting activities with the Chorus. Rather, it is more a public-facing demo for the Orchestra’s revitalized vocal contingent. Hallelujah! and Other Great Sacred Choruses (1962) presents essentially a greatest hits of the symphonic Mass and oratorio repertoire. Certainly, the album’s concept is lighter than what Szell would likely have produced, its popular choral extracts substituting for the larger multi-movement works that Shaw took pride in preparing for collaboration with the Orchestra. But the album does provide a sense of the chorus that Shaw had cultivated around a half-decade into his tenure in Cleveland. Some of its selections give us a tantalizing taste of what a more ambitious recording contract for Shaw and the Chorus might have produced. Listen, for example, to their deft treatment of the Kyrie from Beethoven’s Missa solemnis.

Strangely enough, one of the more compelling (and clarifying) aspects of Shaw’s legacy is not, strictly speaking, musical. He was an exceptionally enthusiastic writer, remembered for his casual, yet carefully wrought letters to the choir — missives that, in addition to providing more businesslike reminders of rehearsals, included discourses on the various musical problems with which his ensemble, or any musical group, was confronted. The letters’ distinctive eloquence, along with the revealing portrait they paint of Shaw as an ensemble leader and musical personality, has led to some of them being published in The Robert Shaw Reader, edited by Robert Blocker. (Original copies of many of these letters can also be found in the Orchestra’s archives.)

These letters show that high among Shaw’s gifts was an ability to render the sublime and the spiritual in practical terms. (It has been suggested by his biographer, Joseph A. Mussulman, and others that this was an inheritance from his upbringing as a minister’s son who intended, as late as university, to take up his father’s vocation.) For Shaw, the communal aspect of choral singing was such an overwhelming spiritual imperative that he was willing to undertake repertoire that might, in theory, sound best with a smaller choir, yet without whittling down the membership of his symphonic chorus in order to do so. Regarding preparations for performances of J.S. Bach’s B-minor Mass, he wrote to his choristers:

“Bach is above all a composer whose understanding and enjoyment are found in participation; his choral writing is undeniably an act of common worship. Were we to cut the ranks of [T]he Cleveland Orchestra Chorus, to allow but one of every five members to participate, it well might be that we would have dusted off the letter of Bach’s law, but killed his spirit.”

— November 5, 1957

(Shaw may eventually have thought better of this approach, as evidenced by a later letter concerning Bach’s Magnificat, dated November 30, 1960, which rationalizes a reduction in performing forces.) When writing his letters, Shaw undoubtedly trafficked in ideas and imagery that might easily curdle into sentimentality in the work of a less purposeful artist; yet he was ultimately too demanding a craftsman to allow the spiritual to be tainted by preciousness.

The quasi-religious aura was hardly lost on contemporary observers. One Chorus member, Michael Swanson (who is also quoted at the beginning of this essay), wrote that “Mr. Shaw’s position vis-à-vis The Cleveland Orchestra Chorus is that of prophet-priest. The choir is his congregation — the score his text. He transmits to his choir the message of Bach or Beethoven as interpreted from the vantage point of his own vision” (“Entr’acte” program essay, 1966).

Biographers tend to stress the contrast between Shaw’s fervent artistry and his vivacious verbal impieties. But Shaw’s virtue cannot be doubted as regards the then-fraught arena of domestic race relations. His extraordinarily successful Collegiate Choir (which was decidedly not a college ensemble), founded in New York in the 1940s, was integrated from the first by its conductor. Of his chorus in Cleveland, his secretary, Edna-Lea Burruss wrote: “Who are the people who make up [T]he Cleveland Orchestra Chorus? They're teachers, students, doctors (M.D., Ph.D.), secretaries, architects, plumbers, housewives, engineers — all races, all religions — each fissured and fractioned by all matters of daily living” (“Entr'acte” program essay, 1963).

Shaw’s quirksome humor — a sure antidote to any over-indulgence in the ethereal side of music-making — is so deliciously zany as to be almost unsummarizable, demanding quotation: “The business of a conductor is to holler “Sheep!” and to holler it so loud so clear so long and so successfully that even the wolves begin to doubt their existence, shuffle off their mortal coils to buffalimbo — has-beens, were wolves” (February 5, 1958). Everywhere in the letters, we find weird, unforgettable exhortations. For example, “We just have to get our haunches in harness” (February 26, 1958), or “The chorus that bays together stays together” (November 30, 1960). The letters reinforce a popular image of the choral conductor as patriarch. We come away picturing Shaw as a sort of choral society’s Father Christmas, an overflowing font of gruff good humor.

A faintly paternal tone underlying the conductor’s letters is a part of their flavor — his affection is palpable and doubtless central to his choristers’ conception of him. These documents date from the midcentury, when an air of beneficence was often part and parcel of the senior music director’s public (and self) conception. Musical paternalism could also manifest less mildly. In his cultural history of the Orchestra, Rosenberg illuminates the extremity of Szell’s expectations for his own musicians, who often bridled under the stress of his musical and professional impositions. Conductor and pedagogue Michael Charry, who worked alongside Shaw as a staff conductor in the late 1950s and '60s, speculates that Shaw, who'd earlier been a chorus master for Toscanini, had acquired that maestro’s “autocratic” mien. Shaw-as-musical-paterfamilias was undoubtedly a man of his time, yet his sincerity and exactitude (to say nothing of his humor) ensures that the overall impression is fatherly.

“He had a great ego ... and rightly so,” Charry says of Shaw; but any potential for grandiosity was effectively short-circuited by the conductor’s acute awareness of his own deficits in early musical training. Shaw may have been prodigiously clever; still, he was no prodigy. His self-education in professional musicianship was hard-won. Charry recollects overhearing Shaw toiling away one day over score study in the offices of Severance Hall (now Severance Music Center). Without the piano background that Szell, Charry, and many conductors take for granted, Shaw’s score preparation in private could be tedious indeed, chords pecked out at the keyboard with considerable effort.

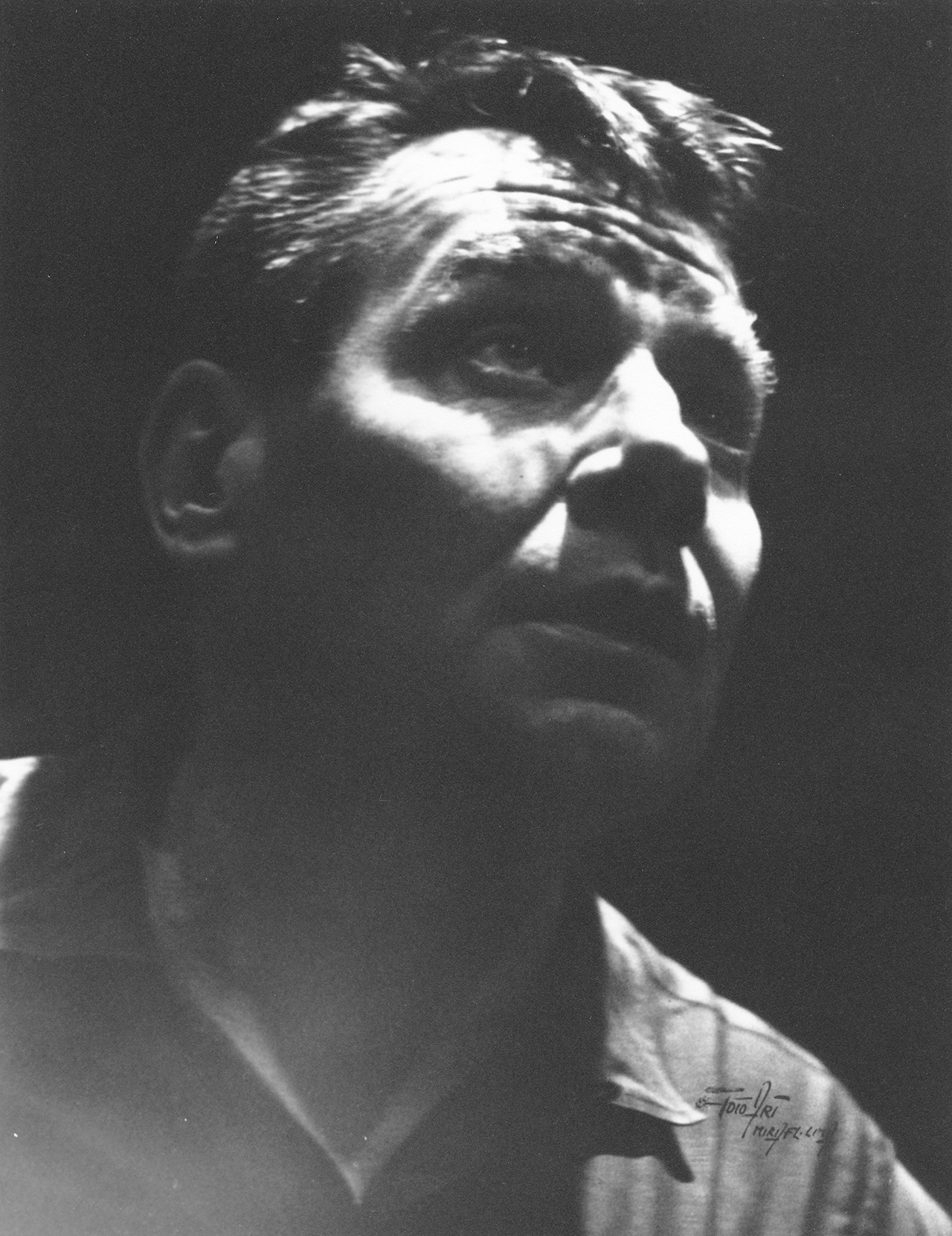

Yet Szell, who could be crushing when his musicians betrayed their own fallibility, was definitely respectful, Charry believes, of the very real, personal trouble that Shaw took in overcoming his lack of youthful preparation for an international-level career in music. Once having prepared his scores, Shaw worked at the highest artistic and professional level as a choral director. “When it came to performing the repertoire that he knew, he was a genius,” says Charry; “his performances were expressive, and dynamic, and hair-raising,” Charry recalls serving as accompanist for some of the Chorus’s rehearsals (as can be seen in the image below), where he was witness to Shaw’s almost terrifying command of the clock, with every precious scrap of rehearsal time predetermined in its use, necessitating exceptionally brisk transitions on the part of the accompanying pianist (as well as the Chorus). “I sweat bullets,” he remembers.

As with all perfectionists, it was the results that mattered — and that would be remembered by listeners. At every stage in Shaw’s career, senior conductors wondered at his almost uncanny instinct for choral transformation. Shaw was a workhorse who, through artistic intuition, intellect, and force of will, made his choral work indispensable to cultural figures as lofty as Toscanini and Szell.

It is probably suggestive of Shaw’s drive and ambition that he was not content to merely prep the chorus before the big show. Though Szell’s principal motivation in wooing Shaw to Cleveland was unquestionably a strategic bid for superior choral forces — which could soar aloft with his orchestra, never weighing it down — it mustn't be shortchanged that Shaw was, in fact, hired as a staff conductor for the Orchestra. Beyond leading regular choral rehearsals, he conducted the Orchestra in myriad concerts, many of them educational events for local children (see the first image, taken from one such event). Programming records for his performances show far more renditions of purely orchestral works than of works with choir. (And, as is usually the case with a symphonic chorus, much of Shaw’s effort was expended in preparing the chorus to be absorbed into a larger musical context for major works that would be conducted in concert by Szell.)

There were, however, significant performing opportunities for members of the Chorus under Shaw’s immediate direction. Especially suggestive is a commercial recording of a pair of Bach cantatas (Nos. 56 & 82) that deploys a stripped-down contingent from The Cleveland Orchestra and Chorus (euphemized on the album cover as the RCA Victor Orchestra and Chorus). Here the Chorus’s role is minimal; these particular cantatas are dominated by solos from the concert baritone Mack Harrell (father of cellist Lynn Harrell, who would later hold an important, early-career post as principal cellist with the Orchestra). This unassuming Bach album is in total contrast to the splashier “Great Choruses” LP, in that it records complete versions of repertoire we know, from the letters, Shaw would have regarded with particular respect and even awe. Here, you can listen to Shaw conduct the chorale that concludes Cantata No. 56.

But the Archives are also home to the previously mentioned non-commercial, live concert recordings by Shaw and the Clevelanders, both from his official tenure in the ’50s and ’60s and from subsequent performances as a visiting conductor (including performances from as late as the 1990s, shortly before Shaw’s death). Here is the opening of Stravinsky’s Symphony of Psalms (recorded live in 1997), which Shaw performed several times over the years with the Orchestra and Chorus. Despite Shaw’s well-earned reputation as a choral popularizer, he did not shy away from modernist repertory — indeed, the letters make clear that these contemporary (or near-contemporary) works mattered to him deeply.

Beyond their remit with the Orchestra, the choristers, under Shaw’s direction, undertook important international work. From 1963–64, a significant portion of their membership acted as resident choir for Festival Casals, performing under the baton of Pablo Casals himself in San Juan, Puerto Rico. (The festival’s performance rosters sport an eye-popping line-up of midcentury luminaries, including Claudio Arrau, Eugene Istomin, and Henryk Szerying.)

The choir’s role in these festivals was not a light one. Choristers would perform major repertory works with the festival’s orchestra, among them, Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, Haydn’s The Creation, Schubert’s G-major Mass, and J.S. Bach’s St. Matthew Passion (sung in an English translation prepared by none other than Robert Shaw!). More unusual were the performances of Casals’s own oratorio, El Pessebre (The Manger), a rumination on the Nativity that was carefully contextualized through program notes and marketing as part of Casals’s broader efforts in the pursuit of a postwar global peace. Shaw and the Chorus’s association with Festival Casals would achieve an apogee through special repeat performances, in collaboration with Casals, held stateside at Carnegie Hall.

Robert Shaw was and remains an original, a peculiar cultural figure not easily cross-referenced with his contemporaries. His success as a choral director, even before his arrival in Cleveland, was so lucrative that, Charry notes, Shaw’s personal financial assets actually exceeded Szell’s. (Charry recalls the splendiferous Bentley convertible Shaw used for his commutes to Severance.) Already, Shaw had been principal conductor at the San Diego Symphony. Szell’s Cleveland ensemble operated on a far more rarefied level, however, and Shaw openly admitted it was an unmissable opportunity for further career development. His shrewdness paid off. After tilling the fields in Cleveland for over a decade, he finally achieved his career-capping tenure as conductor of the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra. He retained his position in Atlanta for many years, resulting in a considerable choral-symphonic recorded legacy (on the Telarc label).

Shaw died in 1999, at the age of 82. Even today, a quarter century after his death, choristers the world over who sang for him remember Shaw as perhaps the closest thing to a patron saint that 20th-century American choral music ever had. Other choral directors, like Roger Wagner in Los Angeles, might vie with him for artistic distinction, but no one seriously approached the breadth of Shaw’s influence on the national choral life. Here in Cleveland, at a crucial juncture in his professional and artistic development, Shaw found the opportunity to work regularly with an orchestra and chorus that could match and further expand his outsized musical vision.

For historical and biographical information, including authors’ observations and interpretations, the following sources were consulted:

- Blocker, Robert, ed. The Robert Shaw Reader. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004.

- Charry, Michael. George Szell: A Life of Music. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2011.

- Mussulman, Joseph A. Dear People ... Robert Shaw: A Biography. 2nd ed. Chapel Hill, N.C.: Hinshaw Music, 1996.

- Oestreich, James R. “Robert Shaw, Choral and Orchestral Leader, Is Dead at 82.” The New York Times. Jan. 26, 1999.

- Rosenberg, Donald. The Cleveland Orchestra Story: “Second to None.” Cleveland: Gray and Company, 2000.

Photographs and non-commercial recordings come from the collection of The Cleveland Orchestra Archives.

A particular debt of gratitude is due to former Cleveland staff conductor Michael Charry, who graciously shared his memories of the Shaw era in an online interview.