Rychtarik’s Cleveland Operas

The Birth of Modern Stage Design

By Michael Quinn

It is difficult to imagine an American symphonic tradition without The Cleveland Orchestra, but the institution’s role in pioneering opera as it is known today during the early twentieth century has gone largely overlooked, as has the man responsible. A romantic story of artistry if ever there were one, Richard Rychtarik’s rise to prominence as one of the world’s foremost stage designers traces a vibrant trajectory of displacement, disenfranchisement, ingenuity, and artistic conviction that revolves around Cleveland. After emigrating from what is now the Czech Republic to Cleveland, Ohio, in 1920, Rycharik found success in designing stages for Cleveland’s famous theaters. But as a student of music, history, engineering, architecture, and literature, Rychtarik knew he could only find creative fulfillment on the operatic stage.

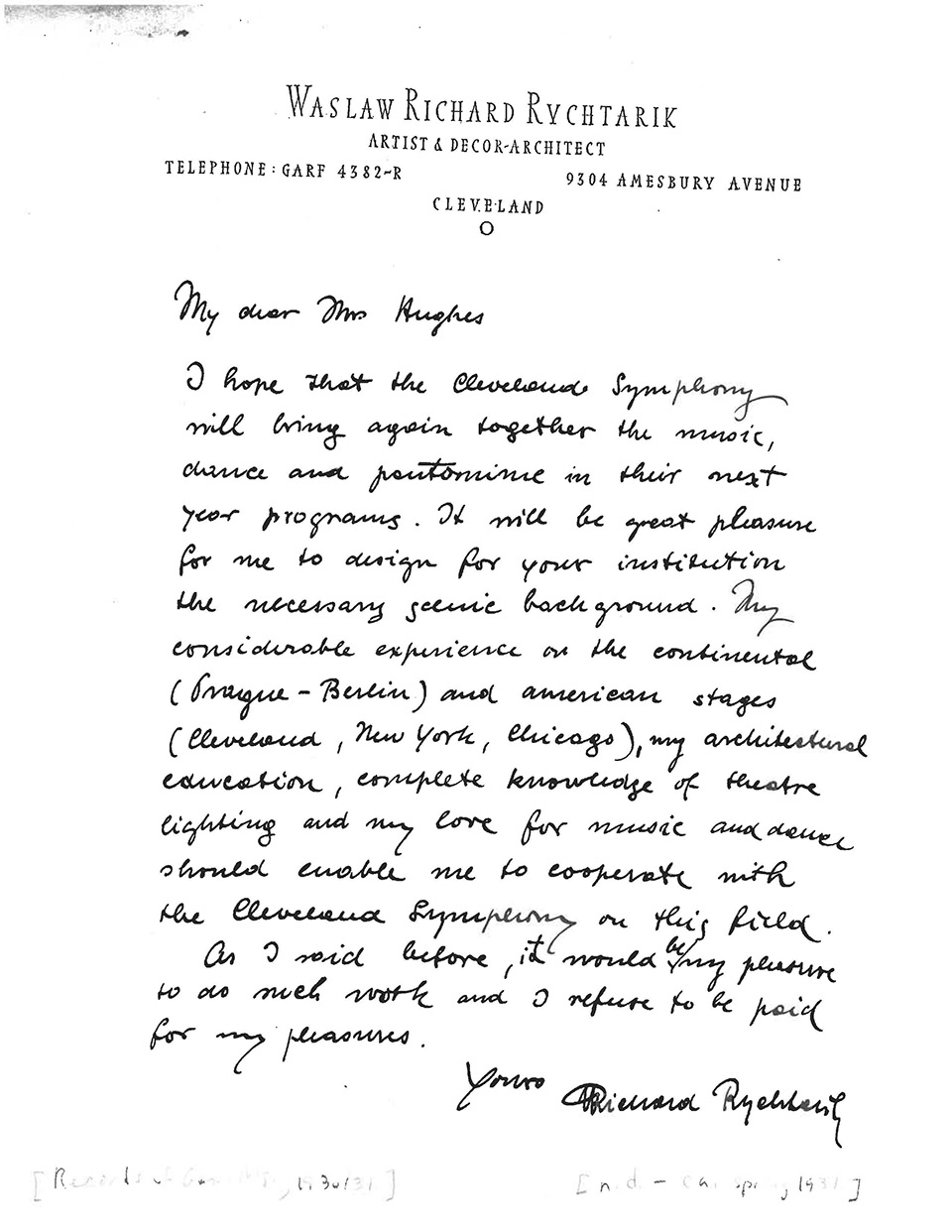

His desire for opera whetted by the traveling productions of the Metropolitan Opera, an eager Rychtarik penned an introduction letter to Adella Prentiss Hughes in 1931, expressing his interest in collaborating with The Cleveland Orchestra. It would not be until three years later, in the midst of the Great Depression, that a letter from the same Mrs. Hughes would launch the young designer’s auspicious career. At the time, the New York Metropolitan Opera had suffered tremendous blows to its finances. A dip into the company’s archives reveals frantic scribbles of boardroom minutes: laundry lists of budget cuts, including omitting Cleveland from its 1933 tour.

No sooner did news of the Met’s cancellation reach Cleveland than the city’s artistic community expressed its refusal to go without opera. As a matter of fact, then-director Artur Rodzinski immediately recognized an opportunity to improve on American opera as it stood and announced his intent to mount a production of Richard Wagner’s monumental Tristan und Isolde, inaugurating a Cleveland operatic tradition through which the young and little-known Rychtarik would carry out his revolution in stage design. Indeed, the Met’s abbreviated tour would mark the beginning of an eager Richard Rychtarik’s operatic involvement. The designer received his long-awaited conscription to design the set of The Secret of Suzanna in 1934. And not unlike Rodzinski, Rychtarik appreciated the blank slate, as it were, offered by a young and experimental opera project. Both perceived in the Met’s operas an over-prioritization of the vocal component that left other elements of the opera underdeveloped. Through Cleveland’s productions, Rodzinski took to raising the standard of the orchestra while Rychtarik would assert the dramatic capabilities of the visual.

Imparting his vision on Cleveland opera was not as simple as convincing audiences of its artistic value at a time when aesthetic movements were especially bound up with nationalist sentiments. The young designer, whose style was forged by the spectacle aesthetics of Continental modernists, found himself working in the midst of post-war nationalism, as countries regathering from years of global disorder sought to define distinctly national identities, and the arts were no exception. But, of all places, Rychtarik would find a saving grace in The Cleveland Orchestra’s meager budget. Indeed, making do with modest resources trumped concerns for any sort of nationalistic integrity; and it so happened that Rychtarik’s took pride in that his modernist style embodied material economy and simplicity, an idea that, as the designer recalled, he had begun cultivating as a young boy while constructing set models from garage scraps.

His artistic economy is epitomized in his stage design for The Cleveland Orchestra’s 1934 production of Wagner’s Die Walküre, in which a set of four three-dimensional graded structures were rearranged to provide a unique setting for each of the four-hour-long opera’s dramatic scenes. And, by all accounts, Rychtarik’s design dazzled audiences. In a 1934 Cleveland Plain Dealer article, Denoe Leedy describes the audience’s reaction: “The giant doors of Hundling’s dwelling flung open to the brilliance of a spring night. As the curtain rose on the second and third acts, so impressive were the forms [Rychtarik] had constructed that that the audience gasped in unison and burst into applause.”

Combined with his vast knowledge of architecture and engineering that made possible sets at once dazzling and economical, Rychtarik’s extensive education in art and music histories instilled in him a conviction that opera was comprised of equal parts visual and audial stimulation. For him, stage elements, when meticulously thought-out, complimented and could even accentuate the undertones and “deeper meanings” of the libretto. It comes as no surprise that the painted backdrops and classical prosceniums that characterized American operatic settings until the early twentieth century had grown tired to Rychtarik’s eyes. On the dramatic level, the designer believed that the stage architect should at once embrace the fantasy of operatic settings and resist the element of the fantastical—something of a paradox. But the designer himself put it best in describing his vision for the staging of Die Walküre during an address to the Women’s Committee in 1934:

“No matter how high we climb the Alps, we will not meet the mighty Wotan nor Brunnhilde. They live on mountains much higher or in ranges lost or not yet discovered. It is my problem to search for such mountains, to create a world in which Wotan and Valkyries are still living.”

The stage designer’s job, as Rychtarik saw it, was to render realistic the conditions of an imaginary world. He theorized that sensory satisfaction was achieved by visually exploiting the dramatic extremes of the music and text on stage, something no less critical to conveying the opera’s subject matter. In other words, the visual should exaggerate the libretto’s dramatic extremes to achieve a “reality of the stage,” even if that reality was entirely implausible. At times, this meant setting an opera adrift into seemingly anachronistic worlds. Particularly in his later stage designs, Rychtarik would altogether abandon audiences’ stereotypical notions of ancient Greece or early modern Europe for polychromatic and mid-century modern stage settings that at once captured the “spirit” of the opera and with which audiences could better identify. Toward this end, stage elements emerged from their two-dimensional backdrops of the nineteenth century and appeared in the foreground among the performers and lighting became increasingly important as an affective device.

To be sure, opera as it developed in Cleveland, caught national attention. Soon after recovering from its financial crisis, the Metropolitan Opera recruited Rychtarik to design the set for its production of C.W. Gluck’s Alceste. Drawing on techniques developed at Severance Hall, Rychtarik would continue designing for opera’s capital stage and be appointed technical director in 1947. One need not look further than the Metropolitan Opera’s 2011 production of Die Walküre for obvious traces of Rychtarik’s legacy. Met stage designer Robert Lepage’s setting for the entire opera centered around 24 rotating bars mounted on a spindle. Depending on their configuration, the bars could act as a cascade, clouds, bucking horses, or mermaids’ tails. Save for the lighting and projections, no new objects were introduced to or removed from the stage over the course of the opera’s four hours, but the contraption morphed into various worlds before the audience’s eyes, not unlike Rychtarik’s versatile stage pieces of 1934. Had he been born into the era of technology that made Lepage’s monstrous machine possible, one cannot help but sense that Rychtarik would have done something along the same lines.

Michael Quinn was a research fellow in The Cleveland Orchestra Archives for the 2018-19 season.