Cleveland’s “Giant Jewel Box”: Building Severance Music Center

By Krista Mitchell (2023)

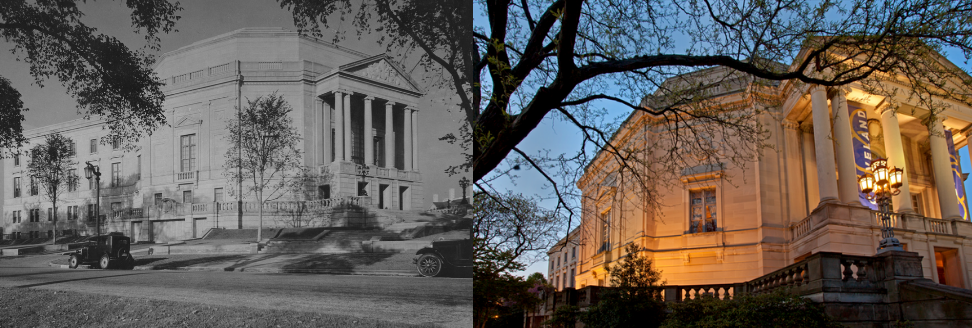

Severance Music Center and The Cleveland Orchestra have been cultural icons in Cleveland for so many decades that it can be challenging to imagine the city without them. Colloquially known as “America’s Finest,” the Orchestra has garnered acclaim throughout its tenure since its founding in 1918. Severance, acknowledged by the Cleveland Landmarks Commission and the National Register of Historic Places, seems permanently embedded in the city’s cultural life as if it were here from the founding of Cleveland. However, the story is less straightforward than expected, and much of our thanks for the beautiful hall enjoyed by thousands today rests with the philanthropy and imagination of several key figures of historic Cleveland.

Even before founding The Cleveland Orchestra, Adella Prentiss Hughes planted seeds for a future concert hall. Hughes stayed busy early in the 20th century by programming and promoting local and visiting musicians through the Fortnightly Musical Club and managing the Symphony Orchestra Concert series. Difficulty securing adequate performance spaces constantly plagued the organizers. Within the first decade of the 1900s, Hughes started writing to philanthropists and famous Clevelanders asking for assistance in creating a dedicated concert hall, but she received constant refusals. Shortly after the founding of the Orchestra, the Cleveland Masons opened Masonic Hall in 1919 and allowed the Orchestra to rent their building for concerts, temporarily satisfying the need for space. However, the Masons’ busy schedule prevented consistent rehearsals for the Orchestra, and scheduling concerts became more of a hurdle.

In the mid-1920s, Hughes resumed her quest for a concert hall in earnest, aided by the investigative work of the Women’s Committee (now called Friends of The Cleveland Orchestra) regarding the viability and location of a music hall. Hughes began collaborating with a local architect, Walter R. McCornack, as early as 1926 to develop these plans. Eventually, architectural drawings, price estimates, and a promising site in University Circle created a clearer picture of a future home for the Orchestra; now, the Musical Arts Association (MAA) and Hughes only needed to secure funding.

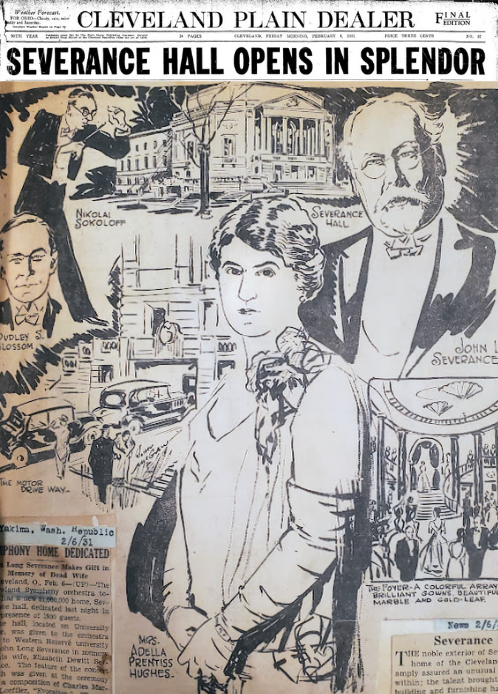

John Long Severance, president of the Musical Arts Association from 1921—36, continuously aided the Orchestra during its challenging early years — even personally paying the salary of the first music director (Nikolai Sokoloff) for a time. Though initially reluctant to donate, the Severances felt encouraged by the planning already in place and the promised donation from Mr. and Mrs. Dudley S. Blossom Sr. for the hall. Late in 1928, John and Elisabeth Severance came forward with a $1 million gift towards constructing a permanent home for The Cleveland Orchestra. They promised this incredible sum with the caveat that the Orchestra must create a $2 million endowment fund and secure the site for the hall. Dudley Blossom Sr. announced this gift to the public at the tenth-anniversary concert of the Orchestra on December 11, 1928.

Fortunately, the MAA quickly secured the location of the new music hall. Robert Vinson, then-president of Western Reserve University (now subsumed into Case Western Reserve University), suggested a mutually beneficial arrangement for this new hall. Philanthropist and industrialist Jeptha Wade originally owned Wade Park in University Circle but donated a portion to the University. If the Orchestra could build a $600,000 endowment fund for upkeep and maintenance, Western Reserve University would give this land to the Orchestra — valued at $600,000 — hoping for continued collaboration to serve the concertgoers of Cleveland and college students alike. Mr. and Mrs. Blossom Sr. kept their financial promise and singlehandedly provided the endowment for the site.

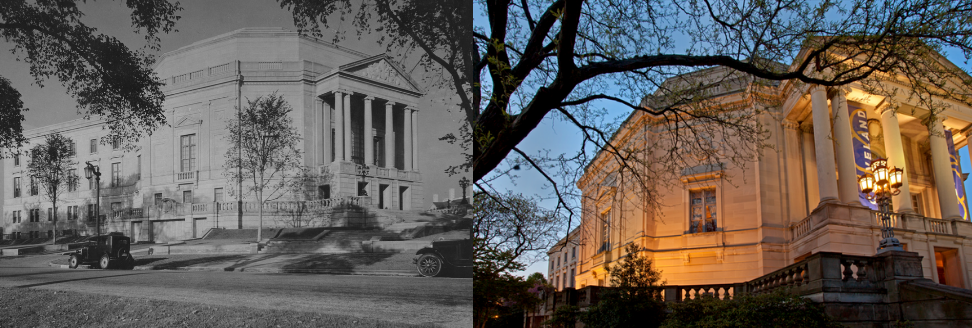

Even with these incredibly generous donations, the project needed more funding. Blossom Sr. served as chair of the endowment fund committee for the MAA. At first, the Executive Board focused on a private, personal campaign for funding, which was quite successful: $2 million from twenty-eight donors. Though John D. Rockefeller Jr., a longtime family friend and professional associate of Hughes, felt hesitant to support a new hall in Cleveland at first, Hughes won him over with the organization and planning she had already accomplished; as a testament to her leadership, Rockefeller Jr. pledged $250,000. In a telegram to Hughes, Rockefeller Jr. wrote, “As a tribute to what you have done in building up and centralizing in so marvelous a way the musical values of the city, I shall be happy to contribute....”

While these generous few provided a solid foundation for the endowment, an anonymous editorial contributor rightfully noted Severance should be “a temple to music, and not a temple to wealth,” and all Clevelanders should feel welcomed and claim ownership of the hall. In the spirit of community engagement, Blossom and over five hundred volunteers executed a nine-day campaign in April 1929 and successfully encouraged nearly 3,000 Clevelanders to donate — with much help from the local press coverage. Everyone seemed excited to participate in building the hall: the Orchestra, Mr. Severance, the general press, and the public.

The year 1929 brought encouraging progress for the Orchestra’s new hall but also tragedy. On January 25, 1929, Elisabeth Severance, the wife of John Severance and a loyal patron of the Orchestra and Cleveland organizations, passed away. Soon, Mr. Severance’s ideas regarding the new music hall began to change. Originally ordering the building team to avoid the elaborate use of bronze and marble, Mr. Severance began desiring increasingly opulent designs with rich materials. Though he did not advertise it publicly for quite some time, this music hall would no longer be merely a home for the Orchestra: it was to be a memorial for his beloved late wife. In the words of the building committee’s chairperson, Frank Ginn, “The plan has been much elaborated and embellished since Mrs. Severance has gone and is to be carried through by Mr. Severance with the thought and purpose of a most beautiful and appropriate memorial.” Mr. Severance’s $1 million donation quickly burgeoned into a nearly $3 million investment. This year also brought the Great Depression, further challenging finances for Mr. Severance and the world. It would take years for him to recover financially from this selfless act.

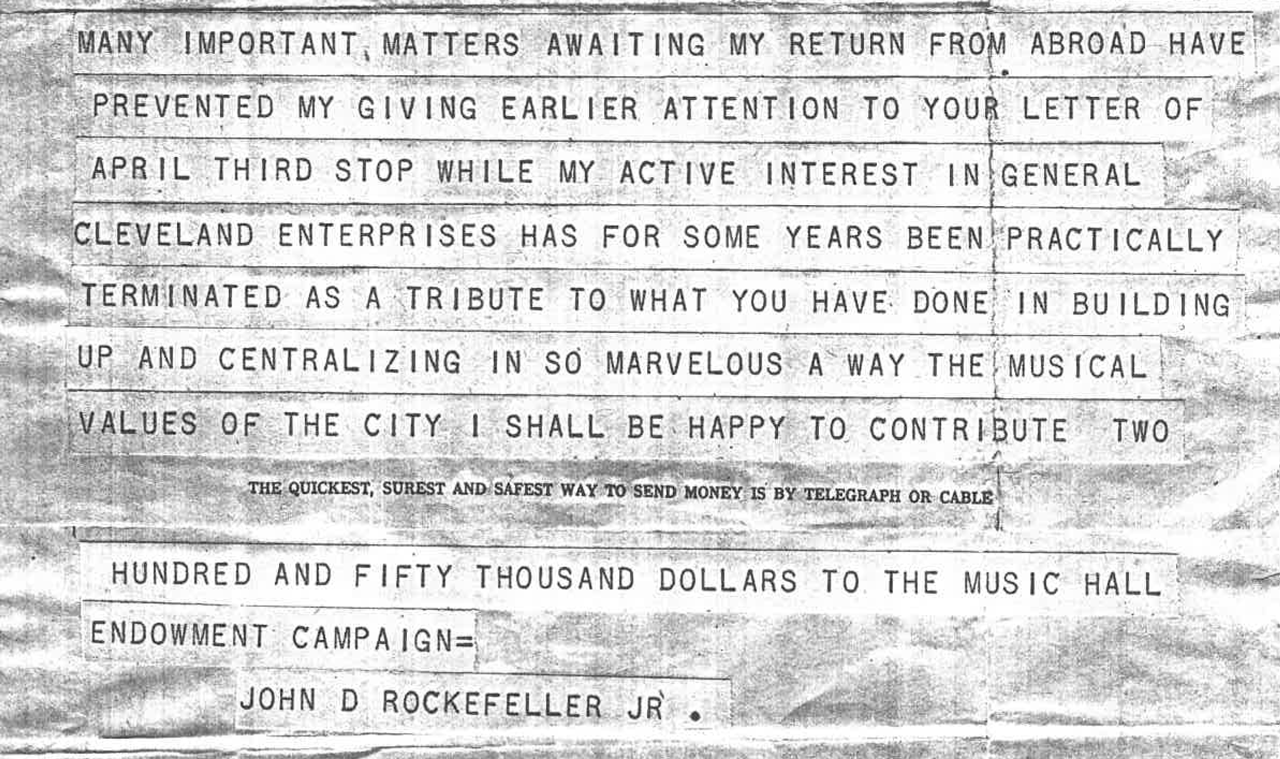

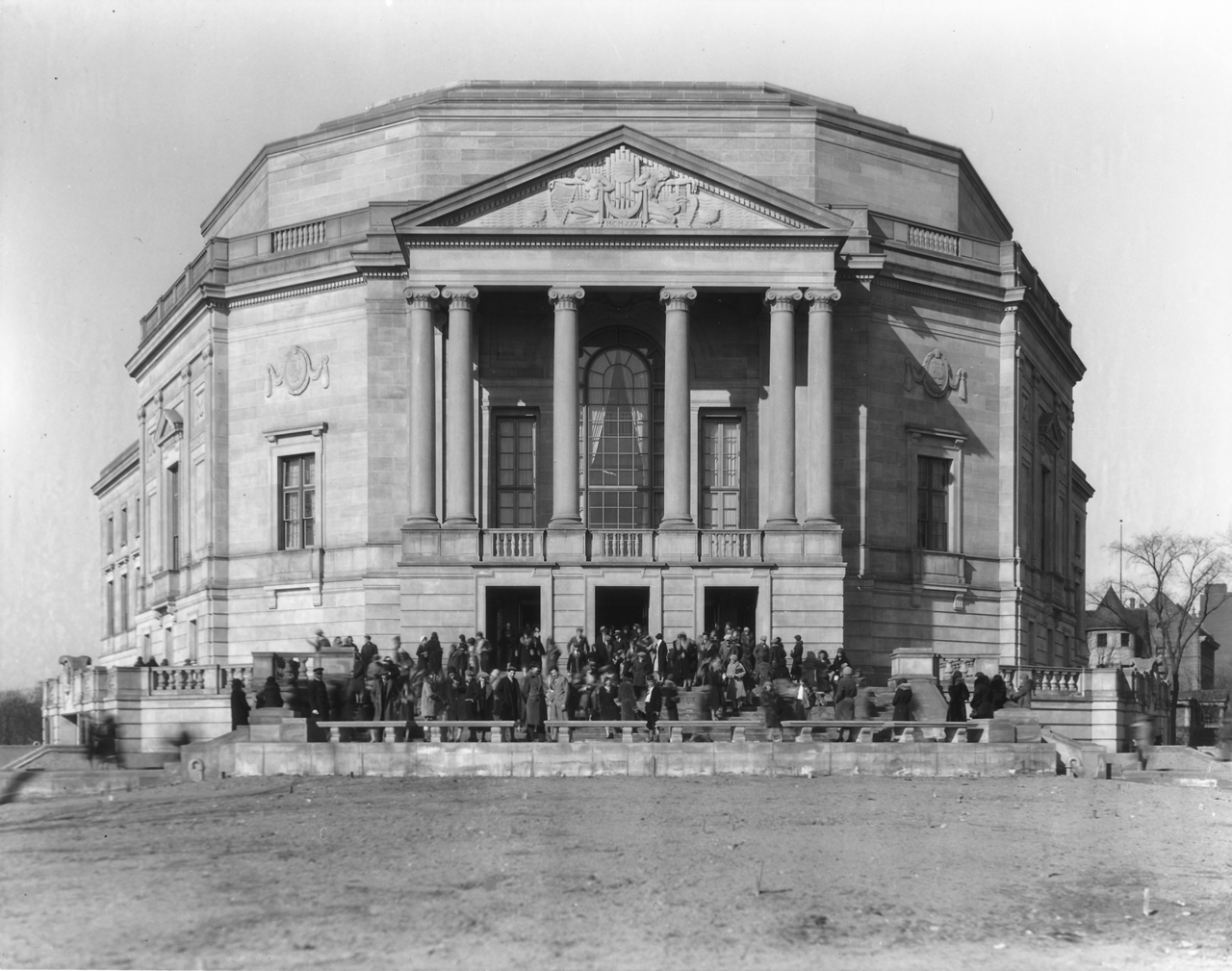

Fortunately for all involved, the MAA chose the perfect designers and building team to create this “appropriate memorial”: architects Walker & Weeks and building company Cromwell & Little. The architecture of Walker & Weeks peppers the Cleveland landscape: the Cleveland Public Auditorium (dedicated 1922), the Federal Reserve Bank (1923), the main branch of the Cleveland Public Library (1925), and the Allen Medical Library (1926), to name only a few. The designers were known for their “planned and harmonious eclecticism,” which shines through in the design and organization of Severance Music Center. Aided by lighting designer S.R. McCandless, acoustical engineer Dayton C. Miller, and McCornack’s original sketches, Walker & Weeks turned an odd, wedge-shaped piece of land into a stunning, functional concert hall.

The nearby Cleveland Museum of Art inspired much of the exterior design. The outer construction of Severance consists of Indiana limestone and Ohio sandstone. The architects wanted the exterior to exude the Classical English manner of the 18th century, complete with columns and carvings. Henry Hering was responsible for the relief carving atop the neoclassical portico at the front of Severance. A motor driveway inside the building would allow patrons and chauffeurs to drop off visitors without lining up in front of the building or necessitating a massive parking lot. Though the exterior of Severance provided neoclassical grandeur, the hall’s interior provided even more decorative palettes, all linked with a unifying element: a lotus flower, supposedly Mrs. Severance’s favorite.

From the portico entrance, visitors walk directly into the Grand Foyer (now the Bogomolny-Kozerefski Grand Foyer) with its distinct Egyptian Revival/Neo-Egyptian style, which was quite popular after King Tut”s tomb discovery in 1922. The foyer is full of bronze, brass, and gold accents, as well as a treasure trove of marble. There are twenty-four red jasper marble columns spaced throughout, imported from Italy. The terrazzo floor also used marble: tiny marble chips within brass outlines form the design of three open lotus blossoms, mirrored in the ceiling design and chandeliers. Clevelander Elsa Vick Shaw painted fourteen murals within the foyer to depict “the evolution of ancient musical instruments.” This opulent, glittering foyer transitions between the Georgian exterior and the more Modernistic interior.

From the Grand Foyer, audience members can walk directly into what is now called the Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Concert Hall. Immediately, the air softens through rich blue hues in paneling, carpeting, and other furnishings. Aluminum leaf shingles adorn the hall’s ceiling in a pattern reminiscent of English point lace and inspired by the lace sleeves of Mrs. Severance’s wedding dress. The main auditorium was intentionally intimate, designed with under 2,000 seats. The lighting design of the original Concert Hall involved musicians playing beneath a cyclorama or “skydome” ceiling with changing color projections manipulated by a light organ. Whereas the Grand Foyer sublimely overwhelms the concertgoer with opulence, the more subdued nature of the hall allows the listener to feel calm, soothed, and ready to receive the music.

In honor of Mr. and Mrs. David Z. Norton — Mr. Norton being the first president of the MAA — a custom organ built by the E.M. Skinner Organ Company of Boston also decorated the Concert Hall. Given by the Norton children, the Skinner organ (now known as the Norton Memorial Organ) is a massive instrument with 6,025 pipes and the largest stop measuring 32 feet long. Directors could move the musician’s console around and even below the stage, allowing various configurations.

Another performance space is the Chamber Hall — now Reinberger Chamber Hall following a $1 million endowment gift from the Reinberger Foundation in 1986. Its atmosphere channels 18th-century music rooms in the neoclassical style. The hall seats 400 people and originally included a small pit for chamber operas. Hand-painted murals of garden scenes wrap around this delicate yet decadent space.

Along with these performance spaces, the building needed places for administrative work and for the musicians to gather, rehearse, record, and stow their items. Mr. Severance himself picked the furnishings, mainly from the 18th century, for the Board Room (now known as the Rankin Board Room in honor of Alfred M. Rankin’s long service in the MAA). There was also a green room, lounges, and the Conductors’ Circle Room. A groundbreaking inclusion for the time was the broadcasting studio, equipped to fit up to 125 players, making Severance one of the first concert halls built with these capabilities. Additionally, smaller studios attached to the two halls served live broadcasting purposes.

The groundbreaking ceremony took place on November 14, 1929, and in less than fourteen months, the hall would open to the public. The Cleveland Orchestra presented its first concert at Severance on February 5, 1931. The Orchestra began with Alexander Goedicke’s orchestral arrangement of Johann Sebastian Bach’s Passacaglia in C minor before John Severance, Dudley Blossom Sr., and Robert Vinson gave introductory remarks. Mr. Severance’s speech lovingly mentioned his late wife, and Blossom Sr. replied, “The duty of accepting from you this beautiful building given in memory of Mrs. Severance is to me, I believe, the greatest privilege of my life.” Blossom Sr. also included the public, noting, “It is in the last analysis a gift to all of the people of Cleveland.” The premiere of Charles Martin Loeffler’s Evocation, a commission for the opening of Severance, followed these speeches. After an extended intermission, during which the audience could explore Severance, the Orchestra concluded its program with Johannes Brahms’s Symphony No. 1.

The building’s opulence stunned audience members and the press. An anonymous writer for The Cleveland News declared, “Severance Hall is, and will long remain, a thing of breath-taking splendor, beggaring description in prose; it represents a notable epoch in the community’s cultural history.” Prominent Cleveland critic Archie Bell deemed the hall “one of the most beautiful temples ever erected to the glorification of the goddess of symphony music.” The opening ceremony received broader national attention, too: Musical America called Severance “a triumph of beauty,” as one example. The final design of Severance proved to be an overwhelming success in almost all aspects.

While much of Severance Music Center’s aesthetics remain, the acoustics needed adjustments after its opening. In 1958, under the supervision of music director George Szell and acoustician Heinrich Keilholz, the sound improved when the largest hall received a new permanent acoustic shell. This new shell consisted of layers of basswood and maple plywood covered by a protective veneer. Between the basswood core and a layer of maple, the shell contained sand up to nine feet high in places. It necessitated the removal of the cyclorama, replaced by matching overhead panels. This construction became lovingly nicknamed the “Szell Shell.” Additionally, red oak replaced the old pine stage for a warmer sound, and workers removed extraneous curtains and carpeting. One unfortunate consequence of the shell was the entombing of the Norton organ; it remained out of use for decades. For a deeper investigation of this renovation, read Michael Quinn’s essay, “The Szell Shell”

As the year 2000 loomed, the Orchestra’s leaders knew Severance needed restoration, expansion, and a playable organ. In 1998, a two-year, $36 million project began to restore Severance’s finer details to their original glory and add space for administrative offices and audience comforts. Under the guidance of David M. Schwarz Architects, Inc., acoustician Christopher Jaffe of Jaffe Holden Scarbrough, and countless others, Severance’s standing as a cutting-edge, aesthetically vibrant music hall was re-established. Music director Christoph von Dohnányi was particularly thrilled about the restoration and installation of the refurbished Norton Memorial Organ, completed in January 2001 (for more, see Kate Roger’s essay ). The refreshed Severance reopened to the public during its gala concert on January 8, 2000 (listen below), sending the message that the Orchestra was ready to take its performances and home into the new millennium.

Listen: Ravel Suite No. 2 from Daphnis et Chloé; Christoph von Dohnányi, conductor (Jan. 8, 2000)

Severance Music Center continues to enthrall audiences today, both with the caliber of music performed and in the aesthetic beauty of the building. In September 2021, the Orchestra announced an unprecedented $50 million grant from the Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Foundation, prompting the name change from Severance Hall to Severance Music Center and the naming of the main performance space: Jack, Joseph and Morton Mandel Concert Hall. In the announcement, Orchestra President and CEO André Gremillet wrote, “This unprecedented gift lays the groundwork for The Cleveland Orchestra’s second century, supporting our long-term capacity to offer extraordinary musical performances and inspiring programs.” Hundreds of thousands have enjoyed their time at Severance, whether inside one of the music halls, rehearsing or studying in the George Szell Memorial Library, or relaxing in Smith Lobby (originally the Motor Driveway area). With the continued support of philanthropic organizations and the broader community, thousands more can continue to enjoy all Severance Music Center offers. As Blossom Sr. anticipated in his dedicatory remarks in 1931:

There are going to be hundreds and thousands of audiences in this beautiful building in the years to come. And every person in every audience is going to adore to come here, whether it be to listen to lovely music or whether it be from some other equally good purpose. And each is going to leave, as we shall leave tonight, with the feeling of peace and joy and contentment just because we have been here.

Krista Mitchell is a research fellow in the Archives of The Cleveland Orchestra for the 2022-23 season. She is a PhD candidate at Case Western Reserve University.

All photographs and audio clips courtesy of The Cleveland Orchestra Archives.