From “Anarchistic Radical” to Concert Hall Favorite

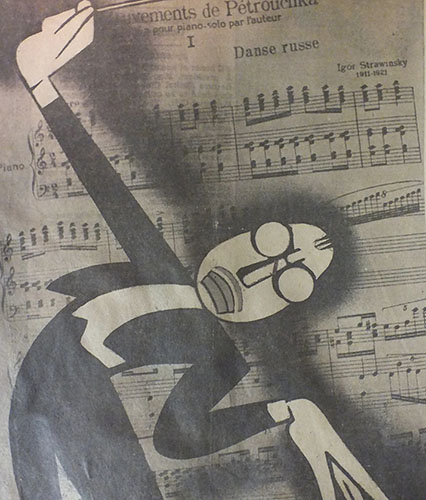

Changing Perceptions of Stravinsky and His Ballet Pétroushka

By Kate Rogers (April 2015)

In 1913, Claude Debussy proclaimed that Igor Stravinsky had "enlarged the boundaries of the permissible" in music. We all know the famous story about the premiere of the ballet The Rite of Spring in Paris that same year, when people yelled during the performance in protest of Nijinsky’s angular choreography and Stravinsky’s daring composition. Since then, however, audience reactions to Stravinsky’s music have changed: in 1953, Lincoln Kirstein, then-director of the New York City Ballet, acknowledged the gradual acceptance of the composer, writing that "sounds [Stravinsky] has found or invented, however strange or forbidding at the outset, have become domesticated in our ears." Stravinsky’s appearances as guest conductor of The Cleveland Orchestra, as well as performances of his iconic ballet Pétroushka in Cleveland, provide but one example of how the great composer transitioned from “anarchistic radical” to concert-hall favorite in the eyes of his audiences.

Stravinsky’s Pétroushka was first performed in Cleveland by Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballet Russes in 1916, the same company that had premiered The Rite of Spring in Paris three years earlier. As The Cleveland Orchestra was not yet in existence, Diaghilev brought his own seventy-eight member orchestra with him to accompany performances, assembled of players from the Metropolitan Opera Orchestra, London Symphony, and Paris Opera, among other organizations. Cleveland audiences turned out in large numbers to see the famous ballet company, though they did not quite know what to think about Stravinsky’s music at the time. Wilson G. Smith of the Cleveland Press referred to Stravinsky as an “anarchistic radical,” stating that his music was “a compendium of atrocious dissonances and unrelated thematic material,” a “galaxy of cacophony.” Alice Bradley of the Town Topics agreed with this opinion; when she closed her eyes to try listening to Pétroushka without seeing the action on stage, she found that “its eccentricities [were] almost unbearable.” James H. Rogers also felt that the score of Pétroushka was “hardly thinkable apart from its pantomimic environment,” though he ended his review on an open-minded note, with the suggestion that “we may hear our symphony orchestras playing it yet. Stranger things have happened perhaps.”

Stravinsky first visited Cleveland in February of 1925, almost ten years after Pétroushka was first performed here by the Ballet Russes. The young composer’s eccentric appearance and mannerisms struck audiences much as his music had nine years earlier. As one Cleveland critic from the Times states, “Maybe he’s a freak, but maybe he’s earned the right to be if he likes it.”

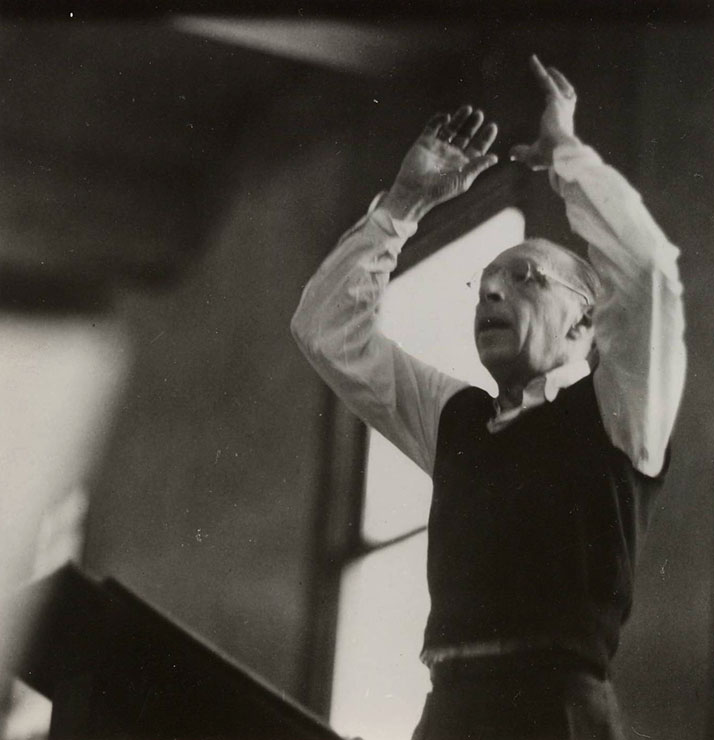

Even though critics and audience members may have been shocked by Stravinsky’s strange personality, they were well-prepared for his music this time. Composer Roger Sessions gave a lecture about Stravinsky’s compositional procedures on the night before the concert, to help audiences better understand the pieces they were to hear the next day. Nadia Boulanger also gave her own lecture, titled “The Evolution of Modern Music,” in the days leading up to Stravinsky’s performances in Cleveland. Stravinsky conducted three of his own orchestral works in his concerts with The Cleveland Orchestra, and these performances were well-received by critics and audience members alike. Eleanor Clarage wrote in the Times about her own reactions to Stravinsky’s appearance and conducting after observing him in rehearsal with The Cleveland Orchestra:

“I saw Monsieur Stravinsky conduct a rehearsal at Masonic Hall Tuesday afternoon. He was there in the famous orange sweater, immaculately groomed, looking very much the suave, polished frequenter of continental drawing rooms, and exhibiting little of the artistic temperament generally expected of such a figure. He has a novel way of presiding over a rehearsal. Swift, concise strokes mark the beat, while he rises on his toes to accentuate a rhythm, pirouetting on one foot oftentimes, like a ballet dancer. Occasionally, in a fortissimo passage, he jumps into the air, landing on both feet with a heavy thud, humming meanwhile in a loud voice.”

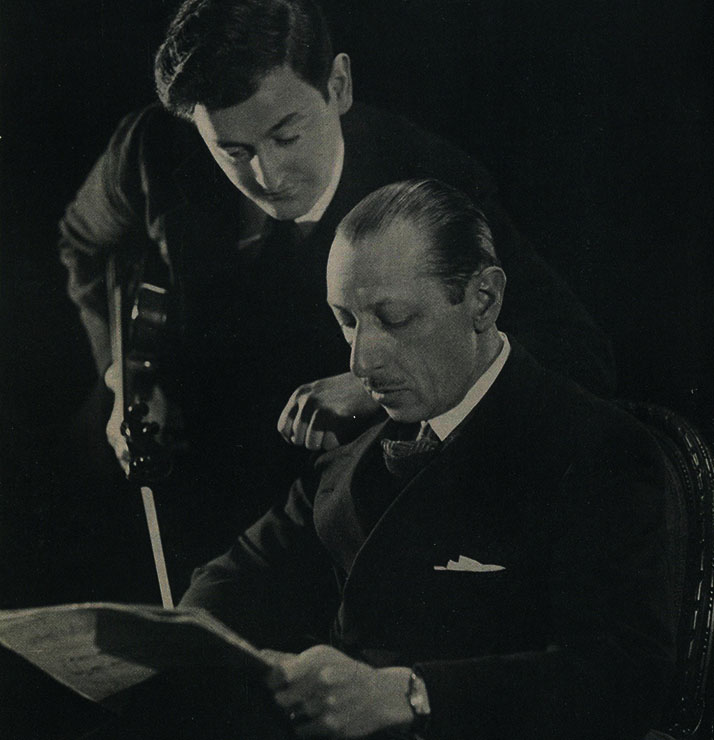

Stravinsky visited Cleveland again twelve years later, in 1937. During this visit, he conducted his Pétroushka suite, his Violin Concerto (performed by soloist Samuel Dushkin), and the divertimento from his ballet The Fairy’s Kiss (Le Baiser de la Fée). Reviewers continued to be simultaneously impressed and shocked by Stravinsky’s music and conducting, but were generally enthusiastic about the composer’s work. As David Eugene Clayman of the Jewish Review wrote, “When Stravinsky conducts, every dissonance, every brassy shriek, every percussive tremor – has a reason for being. It is not as if he merely shook ink from his pen on his music paper.”

Stravinsky returned to Cleveland to conduct a revised version of the first scene from Pétroushka in 1947, the same year he finished reorchestrating the entire ballet. Elmore Bacon of the Cleveland News writes that this new version the scene was “smoothed out for concert performance,” and that “this beautiful music makes us wonder why Cleveland has had to wait years and years to get a performance of this most enjoyable of Russian ballets. Stravinsky put vigor and thrill into this music.” Bacon’s reaction to Pétroushka differs greatly from that shared amongst critics thirty years earlier when the Ballet Russes performed the work: no longer referred to as “a galaxy of cacophony,” Pétroushka now qualified as “beautiful music.” Reactions to Stravinsky’s new music presented alongside the revised Pétroushka scene, however, were largely negative. Some critics cited the music as too mathematical and not understandable without a score. Arthur Loesser even stated that some of Stravinsky’s compositions sounded “a little as if the dregs of the old Pétroushka grapes had been given a couple more squeezes,” suggesting that Stravinsky’s Pétroushka ballet had at this point become so familiar and comfortable to audiences that it was the least shocking piece on the program.

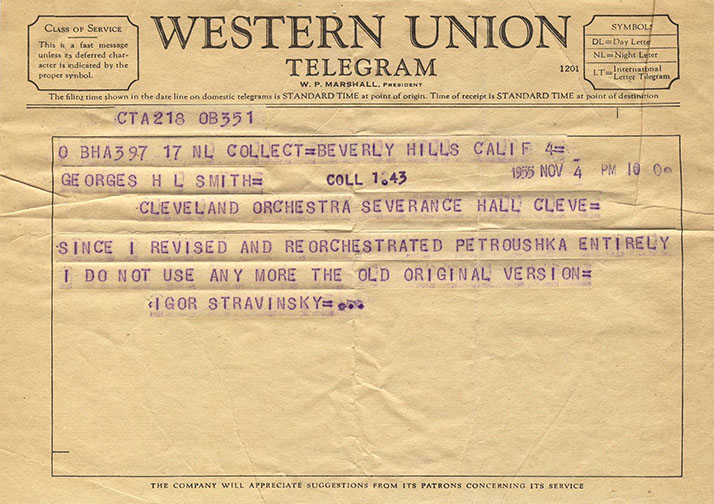

After the success of the Pétroushka scene in Cleveland, Stravinsky returned at the invitation of The Cleveland Orchestra to conduct the full score of Pétroushka eight years later, in 1955. He was adamant about using the revised 1947 version of the score rather than the original: when the Associate General Manager of The Cleveland Orchestra proposed using the 1911 version of the ballet for the Cleveland performances of the work, Stravinsky replied, “Since I revised and reorchestrated Pétroushka entirely, I do not use any more the old original version.”

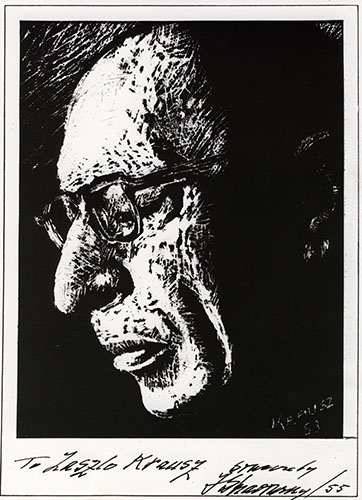

Stravinsky had a wonderful time during his 1955 visit to Cleveland, when he led The Cleveland Orchestra in concert performances of two of his complete ballets, Pétroushka and The Fairy’s Kiss (Le Baiser de la Fée). He said afterwards in an interview, “I have found The Cleveland Orchestra a wonderful musical organization. I am delighted with it and the rehearsals have spoiled me. I am really a happy man batoning this fine group.” The players of the Orchestra were also excited to work with the great composer, and Laszlo Krausz, a violist in the Orchestra who was well-known for his drawings of guest artists, drew two portraits of Stravinsky during the composer’s visits to Cleveland.

Nearly forty years after being deemed a “freak” by Cleveland newspapers, Igor Stravinsky had earned a special place in the city’s classical music community. One reviewer of the 1955 concert describes the memorable evening in detail:

“Cheers and many curtain calls followed the stunning performance of Pétroushka… Stravinsky directs with a decisive beat. Not quite so tall, he resembles Rachmaninoff somewhat. But he can smile. He has won our orchestra and it has won him. So it was another evening of music long to remember.”

Kate Rogers is an intern this season with The Cleveland Orchestra Archives.

She is a PhD student in musicology at Case Western Reserve University.

Looking for more?

The Cleveland Orchestra will be performing Stravinsky’s Pétroushka on April 23 and 25 with guest conductor Susanna Mälkki. Also on the program are Bartók’s Third Piano Concerto played by soloist Jeremy Denk, and Sibelius’s The Oceanides. Click here for details.

To learn more about the plot of Stravinsky’s Pétroushka, click here. This website, put together by the Klavier-Festival Ruhr (Ruhr Piano Festival), includes Benois’s illustrations of costumes and set designs for the ballet as well as short examples of Stravinsky’s music. Whether Pétroushka is one of your old favorites or you are hearing it for the first time this April, this website is a fun and engaging resource for learning more about the ballet.

To read a short biography of Laszlo Krausz, the artist and musician who drew pictures of Stravinsky while he was in Cleveland, click here.