Weird Science

New Technology and The Cleveland Orchestra

The Cleveland Orchestra has premiered countless original orchestral works throughout its history. Additionally, the Orchestra participated in popularizing and using innovative technology, whether in scenic design or instrumentation. While recordings do not exist for many earlier technological feats, their history lives on through archival resources such as photographs, newspaper clippings, and memoirs. This article will briefly feature three technological marvels of their time: the Duo-Art Player Piano, the theremin, and the color organ.

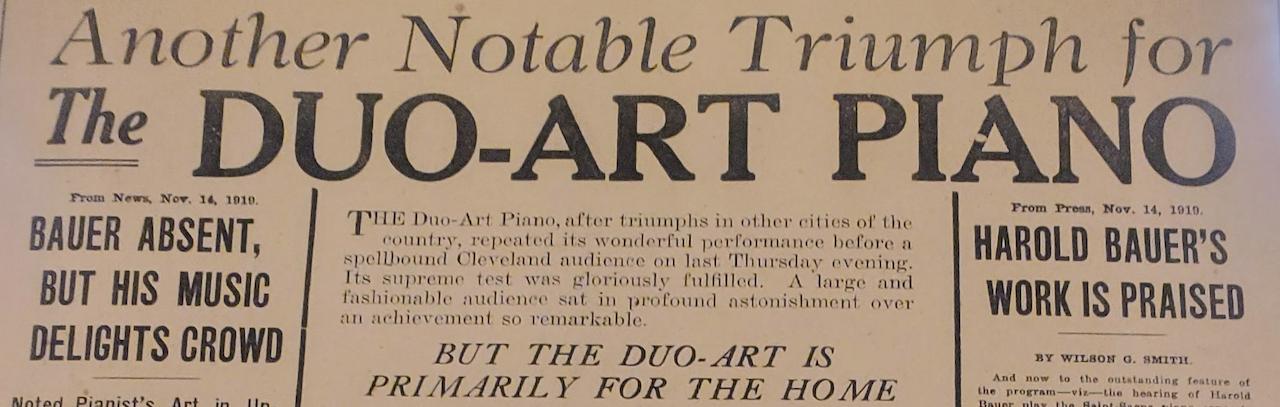

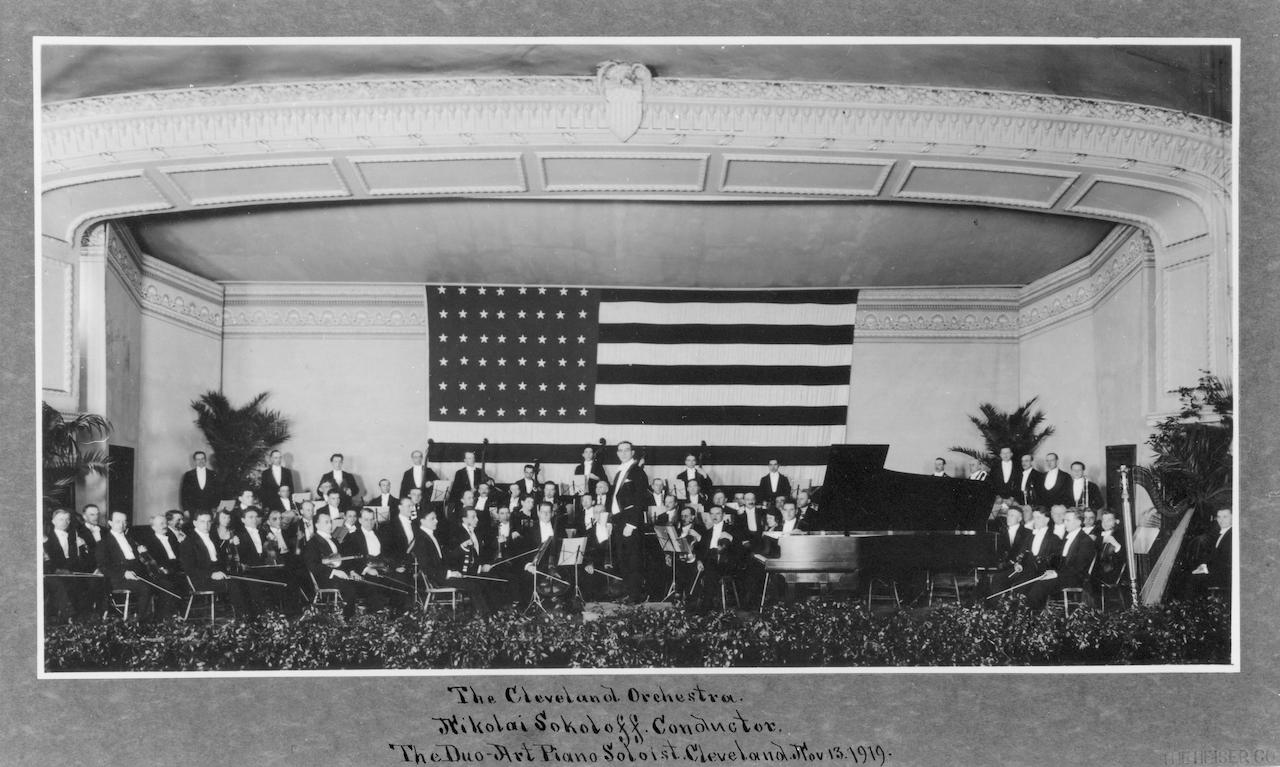

A Haunting Solo: The Orchestra Duets the Duo-Art Player Piano

In an “uncanny” concert from its early years, the Orchestra featured an unconventional soloist: the Duo-Art Player Piano. In November 1919, the Orchestra played two performances of Camille Saint-Saëns’s Piano Concerto No. 2 in G minor, op. 22. However, the human piano soloist (Harold Bauer) was absent from these concerts. Instead of accompanying Bauer himself, the Orchestra performed alongside a player piano programmed with the musician’s rendition. Duo-Art recorded Bauer’s performance onto a piano roll, which tells the player piano what keys to press, and the company lent this roll and a player piano to the Orchestra. Though Duo-Art advertised this instrument for home use, the company thought performances by its mechanical piano with major orchestras could be great publicity. Indeed, the press was impressed. One critic claimed,

“He [Bauer] was there via mechanical spirits, if not in truth and he put across his message with a definiteness and distinctiveness that could not be doubted for authenticity.”

Listen here to Duo-Art’s recording of Bauer’s interpretation of the Saint-Saëns concerto, as reproduced by a 1920 Steinway player piano.

Unfortunately, music director Nikolai Sokoloff — the conductor of this important performance — did not have the easiest experience with the instrument. Sokoloff assumed the piano followed a timed rendition of the entire piece, but he had to “cue” the piano by pressing a button at every entrance. Worse still, the piano played faster during its first performance than in rehearsal, causing Sokoloff and his musicians to perform at a breakneck pace. Sokoloff recalled:

“When we reached the last movement, we were all running hell for leather, with the piano zipping along at a ghastly pace. I was perspiring like a fountain.”

After this experience, perhaps unsurprisingly, the Duo-Art Player Piano did not have any repeat performances with the Orchestra.

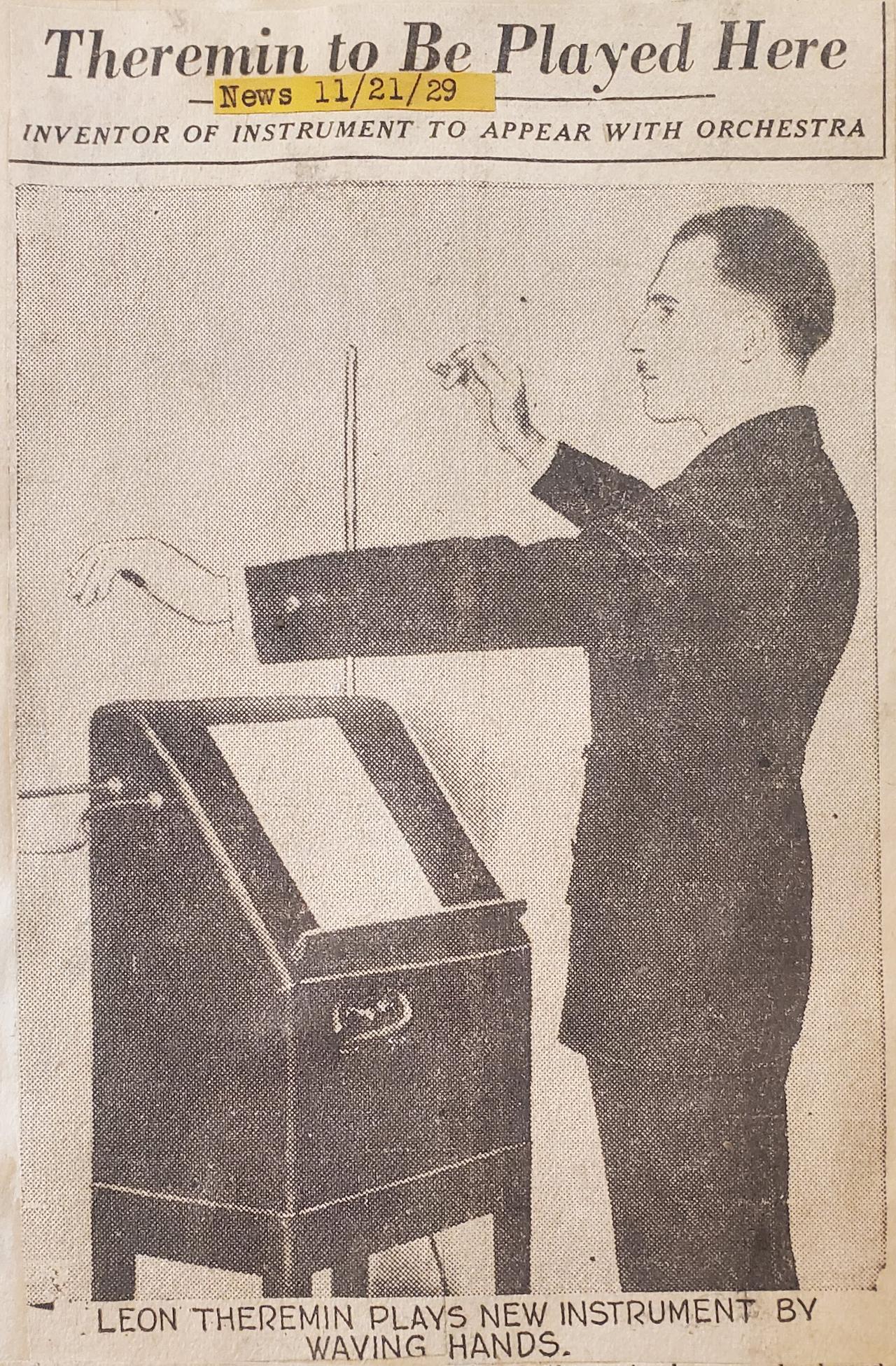

The Theremin and a World Premiere

In 1928, Leon Theremin patented his self-named electronic musical instrument in the United States: the theremin. To play the theremin, a musician moves their hands next to two antennas protruding from the instrument to change pitch and volume. Many audience members today associate the theremin’s eerie sound with science-fiction films, but it was initially much more closely related to orchestral repertoire. Virtuoso Clara Rockmore famously toured with her theremin, playing well-known works with symphony orchestras. Not satisfied with limiting the theremin to existing melodies originally intended for other instruments, composer Joseph Schillinger created a new orchestral suite centered on the theremin: his First Airphonic Suite, op. 21. The Cleveland Orchestra and Sokoloff agreed to premiere this landmark work.

Unfortunately, not all the musicians found the theremin’s timbre pleasant. Regarding his first rehearsal with the instrument, with Leon Theremin playing, Sokoloff wrote:

“I don’t know what happened exactly, but suddenly the thing emitted the most un-earthly, ear-splitting shriek and, to my horror, I saw our wonderful first horn, Isadore Berv, keel over in a dead faint.”

The local press in Cleveland was, at the very least, intrigued by the sound following the suite’s November 29, 1929 premiere. After braving a blizzard to see the concert, critic James H. Rogers claimed, “One listens to it both spellbound and baffled; charmed, too, for the tone that issues from it has warmth, beauty, power.” Nevertheless, the theremin has yet to rejoin The Cleveland Orchestra for a subscription concert as a solo instrument.

Group Synesthesia with the Color Organ

The permanent home of The Cleveland Orchestra, Severance Music Center, opened in 1931. One significant aspect garnering media attention around the hall’s opening was a revolutionary idea for lighting: a color organ. The design team wanted to create atmospheric lighting that could change with the music, allowing for a more immersive experience for the audience. Westinghouse Electric and Manufacturing Co. collaborated with designers to build a remarkable device to control more than 100 electric lighting circuits using the functionality of an organ. A lighting engineer manipulated the lights using the keys and foot pedals just as an organist might control sound. Critics raved about the device. One reviewer noted, “As the music started [the lights] shifted in combinations that the most inventive sunset has never been able to combine.”

In November 1933, Artur Rodziński’s production of Richard Wagner’s opera, Tristan und Isolde, brought the color organ back into the headlines. This production utilized a plain backdrop with ambient lighting rather than a realistic set design. Technical director Max Eisenstat claimed, “The lights will be used at all times to intensify and heighten the effect of the music.” Audiences and critics were thrilled. Although the color organ fell out of use after a few seasons, color returned to Severance with newer, more advanced lighting systems following the hall’s later renovations.

Though not all these forays into new technologies were unequivocal successes, these stories prove the Orchestra has long been invested in innovation and paved the way for new directions in performances of orchestral music. From a new work for theremin in 1929 to the adventurous opera designs of today — such as the brilliant projections in the 2019 production of Richard Strauss’s opera Ariadne auf Naxos — the Orchestra will continue pushing the envelope to engage its listeners worldwide.

All photographs and audio clips courtesy of The Cleveland Orchestra Archives.