The Magic Lens: A Celebration of Chuck Stewart

by Toussaint Miller

At the onset of the Civil War, the abolitionist and scholar Frederick Douglass delivered a lecture on the importance of photography for justice. He argued that while combat might end geographic partition, American advancement and racial reconciliation require the use of pictures. As the most photographed American of the 19th century, it is no surprise that Douglass was well aware of the power of an image to not only influence, but altogether alter our view of the world. He knew that photography had the unique and sincere ability to depict what the eye may not see but is nonetheless present. He understood that this visual art form is so potent because it holds the potential to both honor human life and denigrate it.

Though these meditations were shared in 1861 — 114 years before the invention of the first digital camera — the dichotomy Douglass highlighted could not be any more relevant. Why is it that images of Black repose and play are so hard to come by while those depicting Black trauma and struggle seem unduly pervasive? Why aren’t Black educators depicted as frequently in books and films as Black drug addicts or slaves? Why does the contemporary American zeitgeist have such a limited view of what Black life should look like? As a young Black man attending Harvard University, where the lecture halls are buttressed by ornate portraiture of “the Greats” (few of whom are non-white, and even fewer are of African descent), I wrestle with these questions often. It has become clear to me that the reason the answers are so fleeting is because Black reality has been pigeonholed to exist at the intersection of duality; to live in the tension between bondage and freedom, between equality and a regime upholding racial hierarchy.

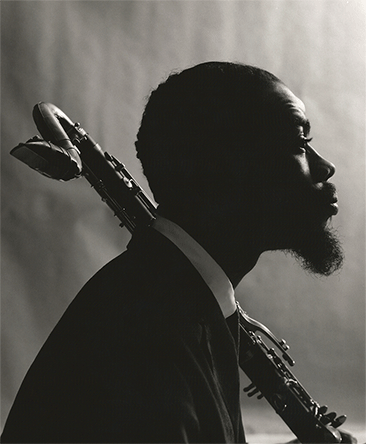

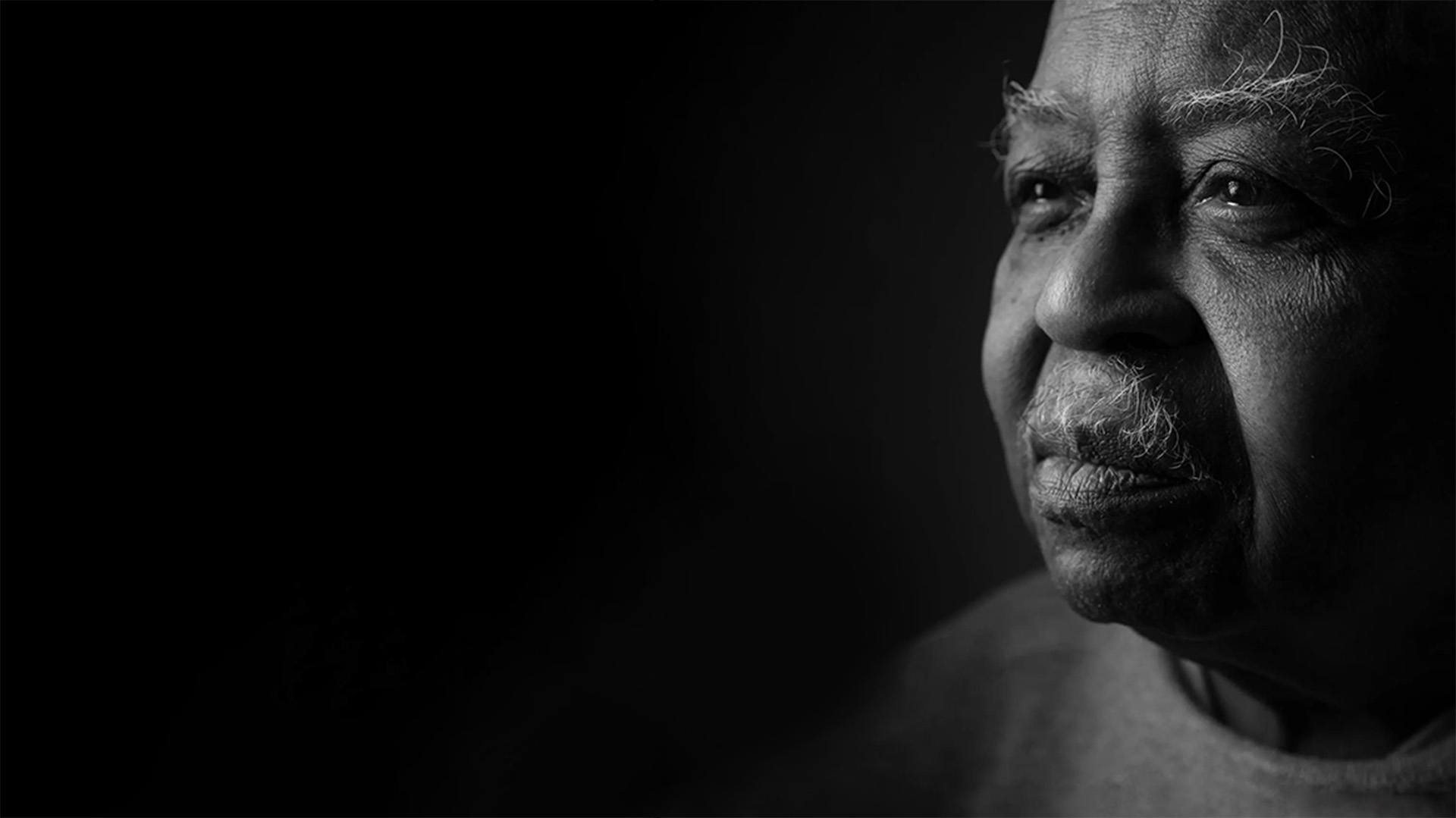

The Magic Lens seeks to uncloak the paradoxical relationship between how Blackness is predominantly portrayed and how it ought to be portrayed. Through the celebration of Chuck Stewart, one of the most prolific American photographers of the 20th century, this exhibition establishes a new canon of Black imagery in an artistic vernacular that seldom makes space for the Black artist. It exemplifies the way in which art can be used as a means of honoring and empowering through three guiding tenets: the power of rhythm, the power of presence, and the power of passion.

The first of the three, the power of rhythm, is apropos not only because of the many jazz musicians that make up this exhibition, but also because of the fine line they balanced between being both in and out of phase with the status quo as enter¬tainers. Gil Scott-Heron, creator of The Revolution Will Not Be Televised and avid Civil Rights activist, embodied this message to the fullest. Images of luminaries including Alice Coltrane and Mary Lou Williams display the power that lies in one’s presence. These artists made space at tables that were never meant to seat them, forcefully claiming each “unalienable right” and realizing the previously unthinkable potential of American democracy by simply existing. The power of passion, the final exhibition tenet, is exemplified through portraits of Eric Dolphy, Dinah Washington, and Arvell Shaw. These creatives were steeped in the rich traditions of their crafts. They likewise understood that the beauty of Black creativity lies in its ingenuity; each iteration of an idea offers a newness that pops off the page or jumps from a rhythm that has been recycled through collective imagination.

The passion necessary to cultivate this gift, to pioneer a resolutely distinct and individual voice, required an assumption of power that was wholly and boldly self-proclaimed.

Through the work of Chuck Stewart and the artistic legacies it encapsulates, The Magic Lens exhibition is a testament to how the transformative power of photography can reshape narratives, reclaim agency, and celebrate the multifaceted richness and resilience of the Black experience.